1. The challenge of maintaining nuclear technology

2021 marks the ten-year anniversary of the nuclear accident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Over the past decade, the situation surrounding nuclear power in Japan has changed dramatically. In 2011, nuclear power accounted for about 30% of Japan’s power supply, but now nearly half of the country’s 54 reactors have been decommissioned, and nuclear makes up just 1.9% of the total power supply[1]. The stagnating use of nuclear energy is a warning light for the status of world-leading nuclear technology in Japan. The development of human resources has also become an issue. For example, the number of students majoring in nuclear energy at universities nationwide has dropped from over 300 in fiscal 2010 to less than 250 today[2]. Some universities have decided to abolish their departments of nuclear engineering[3], and it is likely that more will do so.

Looking elsewhere, China and Russia are exporting nuclear reactors as a part of their national strategies, and they are receiving construction orders from the Middle East and other places that have not previously had nuclear power plants. It is very possible that the number of new nuclear nations will further increase among emerging and developing countries, raising concerns about the proliferation of nuclear technology, which could be used for nuclear weapons.

Japan is the only state without nuclear weapons that has established nuclear fuel cycle[4] technology and has cooperated with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in the global management of nuclear materials. With the domestic market for nuclear energy set to continue shrinking, it is time to consider measures to maintain Japan’s basic technology and human resources in nuclear energy to ensure its continued influence in the field of nuclear non-proliferation.

This article will first outline the risks of nuclear proliferation that can be seen from international trends in nuclear energy, and then examine the significance of Japan’s maintenance of basic nuclear energy technology while considering the limitations of the IAEA’s management of nuclear materials.

2. China and Russia in the international nuclear market and the proliferation of nuclear technology

In Japan, a total of 24 reactors, including six at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, are set to be decommissioned[5]. At the same time, China and Russia are pursuing policies of developing new nuclear power by promoting the construction of new nuclear power plants at home and abroad.

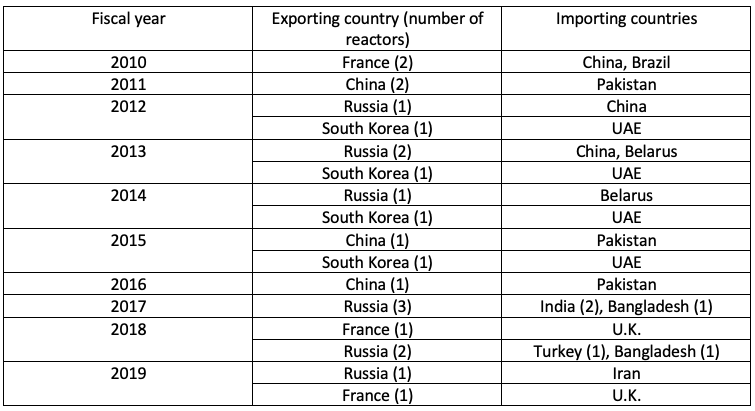

Looking at global nuclear reactor export trends from 2010 to 2019 (Table 1), Russia exported the most reactors (10), followed by China (4) and South Korea (4). In other words, Russia and China are starting to dominate the nuclear export market.

Looking at the “importing countries,” Pakistan and the UAE have imported the most reactors (4), followed by Bangladesh, India and Belarus (2). With the exception of the U.K., which imported two reactors from France in 2018 and 2019, the “importing countries” are mostly categorized as emerging or developing countries, and many of them are new to the use of nuclear energy. Both China and Russia are planning to expand their nuclear reactor exports in anticipation of growing demand for electricity in the Middle East and Africa, and there it is likely that nuclear technology will spread horizontally.

3. Concerns about nuclear proliferation and the limits of the IAEA system

The spread of nuclear power plants increases the risk of the proliferation of all “nuclear” technology.

Specifically, uranium enrichment technology, which is used to turn natural uranium into fuel for nuclear reactors, and reprocessing technology, which is used to extract plutonium from spent fuel for reuse, are technologies that can be used for nuclear weapons. India, in fact, conducted a nuclear test in 1974 by extracting plutonium from a research reactor from Canada[6], and some have noted that North Korea, which has conducted six nuclear tests since 2006, cooperated with the former Soviet Union in establishing its nuclear technology[7]. With nuclear technology set to be transferred to emerging and developing countries, nuclear proliferation cannot be overlooked as a thing of the past.

In response to this kind of proliferation, the IAEA has implemented “safeguards” to verify and inspect the use of nuclear materials.

When the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) came into force in 1970, it established a system of “safeguards” to control the nuclear materials of all member states, including states without nuclear weapons. Japan joined the treaty in 1977[8]. Initially, the IAEA mainly reviewed reports from member states. However, in the 1990s it received greater authority in response to the discovery of inappropriate transfers of nuclear materials from former Soviet states and suspicions over North Korea’s nuclear development program. In 1997 the Additional Protocol was adopted and entered into force, granting the IAEA the authority to conduct unannounced inspections of nuclear facilities in member states[9].

However, if a country that has not adopted the Additional Protocol, such as Iran or Belarus[10], is found to be using nuclear material for non-peaceful purposes, or if a member state refuses to be inspected, the IAEA itself does not have the authority to take steps such as levying economic sanctions or monitoring the traffic of cargo ships. The system simply refers the matter to the United Nations Security Council. As a result, the system is not always particularly effective.

In an effort to supplement these limitations and reduce the risk of nuclear proliferation, the IAEA has called for countries that export reactors to take back the spent fuel from those reactors, and proposed a multilateral framework for managing nuclear fuel cycle facilities that extract plutonium[11]. However, these measures have not been put into effect.

4. The significance of maintaining basic nuclear technology and human resources

Both China and Russia cooperate with IAEA safeguards, and their growing presence in the global nuclear market is not directly linked to proliferation risks. However, there is a risk that the two countries will try to shape international norms to suit their export strategies for nuclear technology and materials. Japan is the only country to have experienced a nuclear attack in war, and it has consistently worked with the IAEA since the end of World War II to ensure the peaceful use of nuclear energy. It is also the only state without nuclear weapons to have established nuclear fuel cycle technology. For Japan to lead in non-proliferation, it will be important to “maintain basic nuclear technology” and “develop human resources.”

To that end, it would be useful for facilities and research institutes in Japan to cooperate with the IAEA’s efforts and to develop human resources capable of implementing the safeguards. It would also be helpful for Japanese institutions to conduct joint research and development with countries that share concerns about proliferation risks into nuclear reactors that can contribute to nonproliferation. In fact, Hitachi-GE Nuclear Energy, founded by Hitachi and General Electric (GE), is developing a new type of reactor that uses plutonium metal fuel, is highly efficient in generating power, and makes it almost impossible to extract weapons-grade plutonium from spent fuel[12]. If these measures lead to an increase in the number of nuclear engineering specialists, Japan will be able to maintain its basic nuclear technology and human resources.

Moreover, as Japan marks the tenth anniversary of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident, the development of new technologies for the safe removal and management of nuclear materials and securing the human resources to do so have become urgent issues if the decommissioning process is to proceed safely. Technologies that can properly remove nuclear materials from nuclear facilities that have ceased operations will help prevent the illegal transfer of such materials.

This kind of technology from Japan, in conjunction with the nuclear material management of the IAEA, can help reduce the risk of international nuclear proliferation. In so doing, it would become a valuable diplomatic asset in security relations, help address the growing number of decommissioned nuclear reactors worldwide, and help strengthen the management of nuclear materials.

(2021/4/13)

Notes

- 1 “Summary of Results [November 2020],” Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, “Electricity Research and Statistics,” February 26, 2021. (Japanese)

- 2 “Can Japan retain nuclear personnel? Experienced personnel decreasing,” Nihon Keizai Shimbun, February 11, 2019. (Japanese)

- 3 Tokai University, the first in Japan to offer a nuclear engineering major, plans to abolish its nuclear engineering department by fiscal 2021. “Tokai University Set to Abolish Nuclear Engineering Department by 2021,” Viewpoint, July 1, 2019. (Japanese)

- 4 A system in which uranium that has not undergone nuclear fission, newly created plutonium and other resources are recovered for reuse from nuclear fuel that has been used in nuclear power generation.“Japan Atomic Energy Relations Organization’s Comprehensive Pamphlet.” (Japanese)

- 5 Federation of Electric Power Companies of Japan, “Decommissioning of Nuclear Power Plants.”

- 6 “The Republic of India,” Japan Atomic Industrial Forum, “Nuclear power making stride in Asia,” January 27, 2010. (Japanese)

- 7 “North Korea’s ‘hydrogren bomb test’ changes ‘dark relationship’ with Russia,” Jiji News, January 19, 2016. (Japanese)

- 8 “IAEA Safeguards (1),” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation,” November 11, 2019. (Japanese)

- 9 As of October 2019, 136 countries, including Japan, are parties to the Additional Protocol.“IAEA Safeguards (2),” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation,” November 11, 2019. (Japanese)

- 10 Ibid.

- 11 For example, in 2005 then IAEA Director General Mohamed ElBaradei announced the “Multilateral Nuclear Fuel Cycle Approach (MNA).” Tadahiro Katsuta, “History of international control on nuclear energy,” Institute of World Studies, Takashoku University, Journal of World Affairs, vol. 55, No. 5, pp. 57-78, May 2007. (Japanese)

- 12 Hitachi-GE Nuclear Energy, “Hitachi-GE Nuclear Energy awarded U.S. Department of Energy Innovative Nuclear Reactor Project,” November 6, 2014. (Japanese)