On December 16, 2022, the Kishida administration approved three new strategic documents: the National Security Strategy (NSS), the National Defense Strategy (NDS), and Defense Buildup Program. Can these documents be considered a historic shift in Japan's defense policy?

It is true in the sense that the Japanese government has begun to consider a realistic strategy for national defense based on the real possibility that Japanese territory could be attacked militarily. This can be considered a turning point in Japan's defense policy since the aftermath of World War II, when the principle of pacifism took precedence.

On the other hand, this is not the first time that Japan has tried to shift its national security policy in response to changes in the international environment. The Contingency Legislation in Areas Surrounding Japan (Shūhenjitai-hō), which was passed in 1999 in response to North Korea's development of nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles in the 1990s, envisaged a contingency on the Korean peninsula and was a major milestone. Another major turning point was the Legislation for Peace and Security (Heiwa anzen-hō) of 2015, which partially authorized the exercise of the right of collective self-defense in anticipation of a peripheral contingency that could have a significant impact on Japan's security, with the Taiwan contingency in mind. In other words, Japan has taken realistic steps forward in its security policy over the past 30 years. The recent revision of the three strategic documents can be seen as an extension of the past defense policy, which has made steady progress, rather than a dramatic shift.

Updates to Defense Documents

What, then, is new about the three defense documents? In a word, it is that the strategy was formulated based on the assumption that Japan's territory could be subjected to a real military attack.

The emphasis in the objectives of both the NSS and the NDS is the strengthening of Japan's own defense capabilities. The NDS states, "Amid the most severe and complex security environment since the end of WWII, Japan needs to squarely face the grim reality and fundamentally reinforce Japan’s defense capabilities, with a focus on opponent capabilities and new ways of warfare, to protect the lives and peaceful livelihood of Japanese nationals.”

The Contingency Legislation in Area Surrounding Japan in 1999 and Peace and Security Legislation in 2015 had security cooperation with the United States in contingencies around Japan in mind. In both cases, the point of contention domestically was the extent to which Japan could exercise its right of collective self-defense, which had not been recognized previously based on government interpretations of the constitution. The Contingency Legislation in Area Surrounding Japan clarified what Japan could do in cooperation with the United States within the scope of constitutional interpretation that prohibited the exercise of collective self-defense in a peripheral contingency. The Peace and Security Legislation changed the cabinet's interpretation of the constitution to allow Japan to partially exercise the right of collective self-defense, thereby broadening the scope of cooperation with the United States and creating more opportunities for contingency planning.

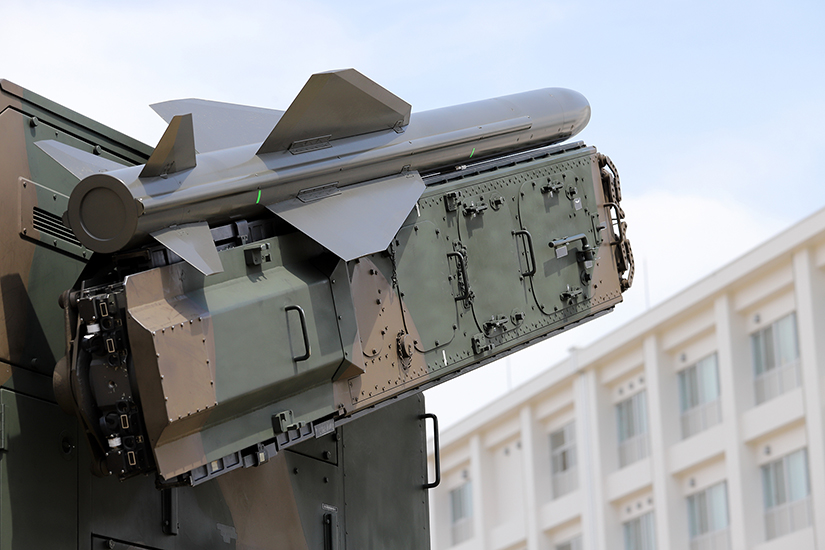

Given the precedent established by the 2015 legislation, the constitutional debate did not feature prominently in the process of formulating the three new strategic documents. In fact, more emphasis was placed on Japan exercising the right of individual self-defense, in other words developing new capabilities to better defend the nation. The NSS recognizes that "Russia’s aggression against Ukraine has easily breached the very foundation of the rules that shape the international order,” and that similar acts of aggression cannot be ruled out in East Asia given the threat posed by Chinese coercion. In this context, Japan is working to fundamentally strengthen its defense capabilities. Specifically, “Japan will respond to situations in a multi-layered way by cross domain operation capabilities that enhance the Japan Self-Defense Forces (SDF) capabilities overall, through the synergy of organically integrated capabilities in space, cyberspace, and electromagnetic domains as well as in ground, maritime and air, and by stand-off defense capabilities and other capabilities that will enable us to respond to invading forces from outside the sphere of threats.”

And based on the recognition that "missile attacks against Japan have become a palpable threat,” a key to deterring against Japan is counterstrike capability that leverages stand-off defense capability. Legally, the justification for counterstrike capability is based on a government statement issued on February 29, 1956, defending the constitutionality of counterstrike capability by noting that "as long as it is deemed that there are no other means to defend against attack by guided missiles and others, to hit the bases of those guided missiles and others is legally withing the purview of self-defense and thus permissible.” The Japanese government concludes on page 4 of the NDS that since these actions are carried out under the three requirements for the use of force as stated at the time of the 2015 Peace and Security Legislation, they are within the scope of the constitution and international law and do not change the concept of exclusive self-defense.

One passage in the NDS that shows that Japan is seriously considering a missile attack not only in theory, but also in reality is that "the top priorities for the next five years are twofold: first, to maximize effective use of its current equipment, Japan will improve operational rates, secure sufficient munitions and fuel, and accelerate investments in defense facilities for improved resiliency; and second, Japan will strengthen its core capabilities for future operations.” Ironically, Japan has neglected the basics of national defense to date, and it can be said that Japan has not considered a military attack on its own territory as an urgent and possible reality until now.

A Change in Public Consciousness of National Defense Issues

Japan's new defense strategy is quite ambitious. The Kishida administration aims to increase the defense budget to 2 percent of GDP within five years (from current level of roughly 1 percent of GDP), but at this point, even within the ruling party, there is no consensus on how to resource the budget, which is already one of the biggest issues driving the policy debate this year.

In this regard, it is undeniable that the Kishida administration did not coordinate adequately within the ruling party, with the junior partner in the ruling coalition, or with the opposition parties, and there was no effort to gain public understanding. Paradoxically, although the public is very dissatisfied with the Kishida administration's poor explanations of plans to secure more resources for the defense budget, there is no significant opposition to the policy direction indicated in the three defense documents. This is in stark contrast to 2015, when public opposition to the legislation related to collective self-defense led to tens of thousands of protesters outside the parliament building. In a December 2022 Nikkei Shimbun poll, 55 percent of respondents support the plan to strengthen defense capabilities over the next five years compared to 36 percent who do not support the plan, despite the fact that most citizens (84 percent in the same Nikkei poll) are dissatisfied with Prime Minister Kishida's justifications for a proposed tax increase to finance defense spending. Interestingly, a December 2022 poll by Asahi Shimbun, which leans left and has staunchly defended pacifist principles in the past, showed a majority (56 percent) supporting acquisition of counterstrike capability. Further, in a November 2022 poll by the conservative Yomiuri Shimbun and NNN (Nippon News Network), 80 percent of the public agreed that China will pose a greater threat to Japan's security as the Xi Jinping administration enters its third term in power, and 68 percent agreed that Japan should strengthen its defense capabilities. Thus, it appears evident that the public is much more aware of the security challenges facing Japan and there is support for the new defense strategy across the political spectrum. This, in turn, should make it easier for Kishida and future leaders to implement key objectives, provided the requisite financial resources are secured.

Rationale for Strengthening Defense Capability with Counterstrike Capability

NSS considers Japan’s “domestic challenges such as a declining and aging population with a low fertility rate and a severe fiscal condition.” In order to survive, NSS concludes that “Japan must ensure as international environment that is conducive to facilitating cross-border economic and social activities such as trade of goods, energy, and food which are essential for industries, and the movement of people.” In order to maintain favorable international environment, Japan needs strong diplomacy, and to solidify this ground, it is important to have a defense capability that can protect one's own country.

Although diplomatically sensitive and therefore only mentioned in abstract terms in the three strategic documents, all concerned share the urgent need for Japan to strengthen its defense capability to continue its existing diplomatic course. The Japanese government has heard the opinions of many experts for revising the three documents, and the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has also announced its proposal to do so. On February 14, 2022, the author testified at a hearing at the LDP's Security Policy Research Council and proposed the need for a counterstrike capability with specific cases in mind.

In the testimony, the author emphasized that in the event of a Taiwan contingency, China could make military threats against Japan on whether to support Taiwan and the United States. The military and political hurdles for refusing to do so are high. At the very least, Japanese leaders should be prepared for a Chinese attack on U.S. military or Self-Defense Forces bases in Japan in order for Japan-U.S. cooperation in the event of a Taiwan contingency. In such a situation, Japan's possession of medium-range missiles with conventional warheads could reduce the effectiveness of intimidation of China and take the "active denial strategy" as suggested by U.S. researchers. The author also warned that if Japan fails to cooperate with the United States in the event of a Taiwan contingency, the Japan-U.S. alliance would become a skeleton, and there would be a risk of more serious consequences for Japan's safety and peace. In the first place, medium-range missiles are an armament held by China and North Korea, as well as South Korea and other countries, and their decision will not destabilize the military balance in the region by upsetting it. Rather, he suggested that Japan should recognize that leaving a power vacuum would have a negative impact on the military balance in the region.

An Important Step toward Deepening the Japan-U.S. Alliance

In the three strategic documents, the strengthening of the Japan-U.S. alliance continues to be recognized as an essential element for achieving territorial defense and regional peace and stability. It is important to note that the drastic strengthening of Japan's defense capabilities is not framed in terms of independent actions from the United States, but rather in the direction of deepening Japan-U.S. cooperation.

This is most evident in the references to acquiring counterstrike capability: "While the basic division of roles between Japan and the United States will remain unchanged, as Japan will now possess counterstrike capabilities, the two nations will cooperate in counterstrikes just as they do in defending against ballistic missiles and others. " In fact, the operation of standoff missiles, like missile interceptors, requires the strengthening of intelligence gathering and analysis functions, command and control functions, and integrated targeting operations, and it is necessary to consider joint operations between Japan and the United States a prerequisite.

Building on the three new strategic documents, the U.S. and Japanese governments announced plans to enhance Japan-U.S. defense cooperation at the 2+2 meeting between their foreign and defense ministers on January 11, 2023, which were endorsed by Prime Minister Kishida and President Biden during their meeting at the White House on January 13. Japan's decisions on defense strategy will be irreversible based on a realistic change in the public's perception of the security environment and will also be an important step toward deepening the Japan-U.S. alliance.

This article was originally published on Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) on February 13, 2023.

(2023/03/14)