The Region’s Importance to Afghan Stability

The US military completed its withdrawal from Afghanistan on August 31, fueling speculation in the media and elsewhere that China and Russia would step in to fill the vacuum left by the United States.

Some observers note that China and Russia are similarly bolstering their presence in many of Afghanistan’s Central Asian neighbors—namely, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan. Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, for example, conducted joint military exercises with Russia in early August[1], prior to America’s withdrawal, and in mid-August, Tajikistani and Chinese security forces conducted anti-terrorism drills[2]. In “A Post-American Central Asia,” published in Foreign Affairs, Central Asian expert Alexander Cooley points to “profound shifts in Central Asia’s political dynamics” and great-powers competition since the US-led, post-9/11 military campaign in Afghanistan in 2001[3].

While much attention has been given to the foreign policy of external powers like China and Russia, little attention is being paid to the contrasting ways in which Afghanistan’s Central Asian neighbors have responded. For example, Uzbekistan hesitated to accept Afghan soldiers and refugees fleeing across the border as the situation destabilized, while Tajikistan took a more welcoming stance[4].

Figure 1. Map of Central Asia[5]

The purpose of this paper is to compare the reactions of Central Asian countries, with a focus on Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Having a grasp of the diverse range of regional responses is of crucial importance not only to China and Russia but also for Western developed countries, including Japan. The paper will then offer strategies for Japan’s engagement in the region going forward.

Tajikistan: Vigilance against the Taliban and Concern about Ethnic Tajiks

Tajikistan has been conspicuous in its behavior concerning the Afghan situation as Kabul was falling. In addition to conducting joint military exercises with China or Russia, as mentioned above, it mobilized 20,000 reservists[6], and accepted former members of Afghan security forces seeking asylum[7].

Dushanbe’s policy toward Afghanistan had been characterized by its vigilance against the infiltration of extremists and its tough attitude toward the Taliban—given the threats posed by the influx of extremists and militants in the past. In 2010, for example, an ambush on a military convoy near the Afghan border resulted in the death of 23 soldiers[8], and in 2015, Gulmurod Khalimov, a lieutenant-colonel and commander of the Tajikistan police special forces who had received anti-terrorism training in the United States, made a surprise defection to ISIS[9]. Riots that broke out at Tajikistan prisons in 2019 also seemed to made the Tajik regime quite nervous about extremist threats to its security.

The Taliban has reportedly placed the Jamaat Ansarullah—a Tajik “terrorist” group that fled to Afghanistan after the Tajikistan civil war ended in 1998—in charge of the country’s border with Tajikistan[10]. This has alarmed the authoritarian regime of President Emomali Rahmon, who has been the leader of the country after winning the civil war.

Tajikistan is concerned about ethnic Tajiks living in Afghanistan, who are said to outnumber the Tajiks in Tajikistan[11]. Dushanbe has called for an inclusive government in Kabul and appears worried about potential discrimination against the Tajik minority. Opposition politicians have been more vocal in criticizing the Taliban’s oppression of ethnic Tajiks and invoking the memory of guerrilla commander Ahmad Shah Massoud, who led the anti-Taliban resistance in Panjshir[12]. The level of concern regarding their “compatriots” in Afghanistan appears higher than for the ethnic kin in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.

Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan: Eager for Engagement with an Eye toward South Asia

Unlike Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan appear eager to engage with the Taliban in the hope of securing economic access to South Asia.

For example, Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev proclaimed on August 27 that his government had been communicating with the Taliban for the past two years[13], and Taliban leaders were reported to have visited Uzbekistan in 2018[14]. In April 2021—prior to an international conference in July (see below)—the Uzbek foreign minister met with Taliban officials in Qatar to discuss the Afghan peace process, at which the Taliban expressed gratitude for Uzbekistan’s support in the energy and logistics sectors, adding that Afghanistan can serve as a bridge of trust and cooperation between Central and South Asia[15].

One possible reason for Uzbekistan’s continuing dialogue with the Taliban is its strong interest in broadening access to South Asia. Uzbekistan is one of only two double-landlocked countries in the world (the other being Liechtenstein), so overcoming logistical hurdles is a key consideration in President Mirziyoyev’s efforts to attract foreign investment. Improving transport networks was one of the main issues discussed at an international conference on connectivity with South Asia, hosted by Uzbekistan in July[16]. An experiment in May conducted with support from USAID showed that it took five days for a truck to travel from Karachi, Pakistan, through Afghanistan to the Uzbek capital of Tashkent[17].

That said, how concerned is Uzbekistan about extremism? In the past, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) was a veritable threat, regarded as being responsible for an assassination attempt on the country’s first president, Islam Karimov, and a number of terrorist bombings. And in 1999, this extremist group kidnapped Japanese mining engineers and their interpreter along the border with Kyrgyzstan (who were later freed). But the group has a significantly diminished presence today following the death of its leader and its merger with the Islamic State[18].

Uzbekistan, as mentioned above, has been reluctant to accept Afghan refugees. In late June, the Uzbek government denied entry to former Afghan government soldiers seeking asylum at the border[19]. While Tashkent subsequently set up a refugee camp near the border with Afghanistan, the refugees were later repatriated. These developments suggest that Uzbekistan is concerned about the infiltration of destabilizing elements into the country[20]. On the other hand, Uzbekistan has allowed many transit flights for countries—including Western ones—to evacuate their citizens out of Afghanistan[21] via its several international airports[22].

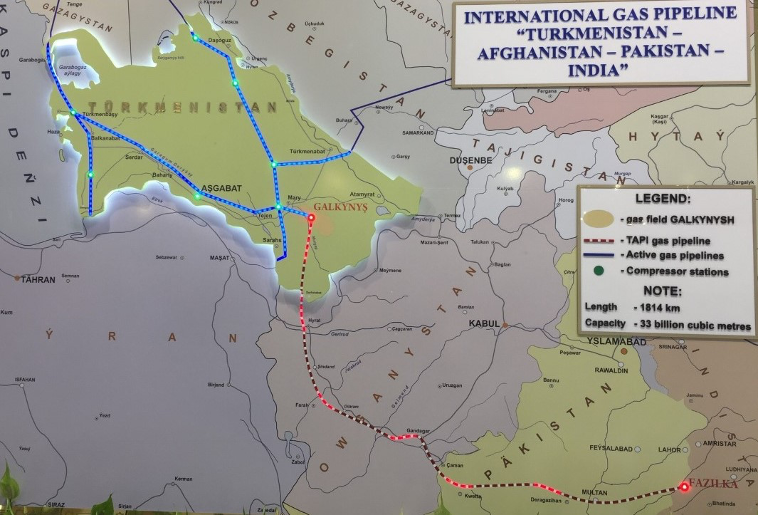

Little has been reported about Turkmenistan’s response to the fall of Kabul[23], so this paper will only mention the situation surrounding the TAPI (Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India) pipeline project.

Of the post-Soviet republics, Turkmenistan has the second largest natural gas reserves after Russia. The TAPI project seeks to connect the country with South Asia via Afghanistan (Figure 2), enabling it to diversify the destination of gas exports beyond China[24].

Figure 2. The TAPI Gas Pipeline Project

In February 2021, the Taliban sent a delegation to Turkmenistan to explain that the new regime would not seek to disrupt the TAPI project[25]. And this pledge was apparently confirmed at a meeting between the two parties three days after the Taliban took control of the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan border[26].

What Japan Should Do

From the above, one can see that (1) Central Asian countries perceive the threat of the Taliban in different ways and (2) some are concerned about the security of land routes to South Asia. How the latter will unfold is still uncertain, and there are limits to how Japan can engage with and contribute to the region[27]. But it can nonetheless help meet these countries’ heightened need to defend their borders with Afghanistan.

Japan already provides region-wide assistance through grants to international organizations, namely, the partnership projects on border management with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC)—which was referred to in the joint declaration issued at the Fifth Foreign Ministers’ Meeting of the “Central Asia plus Japan” Dialogue in 2014[28]. The projects include setting up joint border inspection stations with relevant government agencies, such as border security forces, customs authorities, and interior affairs ministries, as well as establishing command centers for border management at the headquarters in various capitals.

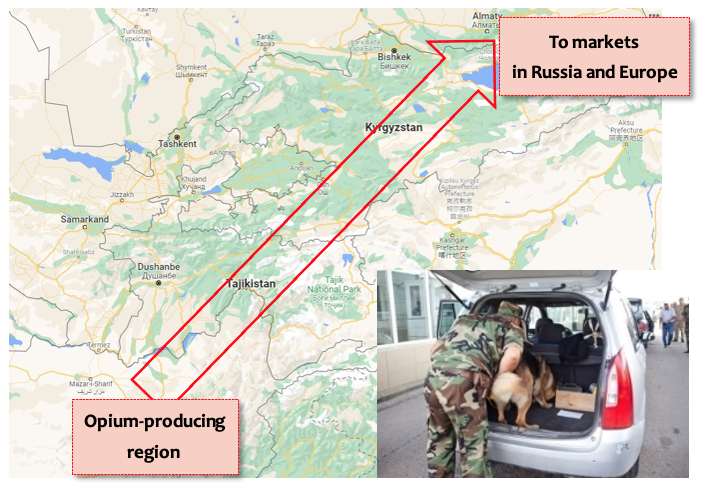

Another concern—shared by Russia and Western developed countries—is the flow of drugs from Afghanistan. Both international and local authorities are intensifying their monitoring of the trafficking of Afghan opiates through the mountainous regions of Central Asia to Russia and Europe (Figure 3)[29].

Figure 3. The Trafficking of Afghan Drugs through Central Asia

Japan has been providing grant aid for UNODC-led border management initiatives in Kyrgyzstan and its neighbors since fiscal 2013. In 2020, the focus of aid shifted to Uzbekistan, with the UNODC regional office for Central Asia in Tashkent serving as the main counterpart and the scope of its activities expanding to cover the entire region. While Japan provides hundreds of millions of yen in grant aid to international organizations, the border security agencies of Central Asian governments are barely able to cover costs with assistance from donors. Increasing the number of Central Asian countries to which Japan offers capacity building assistance in border security would be a very timely move.

The Japanese government has sought to encourage Afghan participation in the Central Asia plus Japan Dialogue[32] in the past, such as by inviting the Afghan foreign minister as an observer[33]. Given the uncertain direction of the new Taliban regime, though, Afghanistan’s admission into the framework will take time. Japan should continue closely monitoring the situation to ascertain local needs and expand its assistance to the region while also drawing on its experience to date in preparing to assist Afghanistan however it can.

(2022/01/11)

Notes

- 1 “Roshia Chuo Ajia no kuni to gunji enshu: Kono chiiki de no eikyoryoku kyouka e,” NHK, August 6, 2021.

- 2 Tsukasa Hadano, “Chugoku, Tajikisutan to han-tero enshu: Kageki-ha no ryunyu o keikai,” Nikkei, August 19, 2021.

- 3 Alexander Cooley, “A Post-American Central Asia: How the Region Is Adapting to the U.S. Defeat in Afghanistan,” Foreign Affairs, August 23, 2021.

- 4 “Afugan kinrin sankakoku no hanno wa: Nanmin ukeire o hyomei suru kuni, migamaeru kuni,” Courrier Japon, August 17, 2021; “10-man nin ukeire kano Afugan nanmin: Tajiku,” Jiji.com, July 24, 2021.

- 5 Source of map: https://www.un.org/geospatial/content/central-asia

- 6 “Дастури Раҳмон барои интиқоли 20 ҳазор низомии эҳтиётӣ ба марз бо Афғонистон,” Sputnik, July 5, 2021.

- 7 “Afghanistan: Soldiers flee to Tajikistan after Taliban clashes,” BBC, July 5, 2021.

- 8 “Islamist blamed for attack in Tajikistan that killed 23 soldiers,” The Guardian, September 20, 2010.

- 9 Dugald McConnell and Brian Todd, “ISIS fighter was trained by State Department,” CNN, May 30, 2015.

- 10 “Exclusive: Taliban Puts Tajik Militants Partially In Charge of Afghanistan’s Northern Border,” Radio Free Europe, July 27, 2021.

- 11 As of 2003, there were 4.5 million ethnic Tajiks living in Tajikistan and 7.2 million in Afghanistan. Over half the world’s Tajik population live in Afghanistan. Hisao Komatsu, Chuo Ajia o shiru jiten, Heibonsha, 2005, p. 318.

- 12 “Демократы Таджикистана назвали действия «Талибан» геноцидом таджиков в Афганистане,” AsiaPlus, August 20, 2021.

- 13 “«Мы прогнозировали, что эти события произойдут». Президент — о ситуации в Афганистане,” газета.uz, August 27, 2021.

- 14 “Taliban holds talks in Uzbekistan,” Eurasianet, August 13, 2018.

- 15 “Глава МИД Узбекистана встретился с главой офиса «Талибан» в Катаре,” газета.uz, April 12, 2021.

- 16 “Chuo Ajia, Minami Ajia chiiki togo e kokusaikaigi: Afugan wahei uttae,” Nikkei, July 17, 2021.

- 17 “Из Пакистана выполнен первый рейс в рамках Конвенции МДП (TIR),” газета.uz, May 6, 2021.

- 18 “Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan O’zbekiston Islomi Harakati,” Public Security Intelligence Agency.

- 19 Mинистерства иностранных дел Республики Узбекистан, “Заявление Министерства иностранных дел Республики Узбекистан,” June 24, 2021.

- 20 “Uzbekistan Sends Afghan Refugees Back Home, States Taliban Won’t Persecute for Fleeing,” Newsweek, August 20, 2021.

- 21 Over 2,000 German, Russian, American, Swiss, and other foreigners had left Afghanistan via Uzbekistan as of the publication of this article: “Через Узбекистан из Афганистана эвакуировано почти 2000 иностранных граждан,” газета.uz, August 20, 2021.

- 22 Most international flights of regional airports are to and from Russia carrying migrant workers.

- 23 “More Turkmen Troops Killed Along Afghan Border,” Eurasianet, May 28, 2014; “Turkmenistan: Don’t love thy neighbor,” Eurasianet, March 19, 2019.

- 24 Pipeline construction plans initially included US companies. Murat Sadykov, “Turkmenistan Draws Attention to Gas-Expansion Plans,” Eurasianet, March 28, 2013; “Taliban vows to guarantee safety of trans-Afghanistan gas pipeline,” Eurasianet, February 6, 2021.

- 25 “Turkmenistan: As Taliban arrives at the gates, diplomats and army scramble,” Eurasianet, July 13, 2021.

- 26 “Turkmenistan: Taliban of brothers,” Eurasianet, August 24, 2021.

- 27 Many more logistic and energy-related projects spanning Central and South Asia exist, but most have been grounded due to lack of funding. The Japanese government had once considered providing ODA to the Iranian port of Chahbahar for its potential to become a logistics hub from the Persian Gulf to Turkmenistan (subsequently funded by India). “Seifu, Iran de kowan keikaku: Indo to kumi shien,” Nikkei, May 8, 2016.

- 28 Fifth Foreign Ministers’ Meeting of “Central Asia plus Japan” Dialogue, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, July 16, 2014.

- 29 Based on interviews with local government officials and aid workers.

- 30 Based on interviews with local government officials and aid workers.

- 31 Photo courtesy of MOFA’s ODA newsletter, December 27, 2019.

- 32 The need for Afghanistan’s participation was pointed out during discussions of specific themes. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “6th Expert Meeting on Clean Energy Development and Implementation of New Possibilities for Central Asia,” March 24, 2021.

- 33 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “Foreign Minister Kono Attends the Seventh Foreign Ministers’ Meeting of the ‘Central Asia plus Japan’ Dialogue,” May 18, 2019.