Introduction

This essay will examine the deployment of military forces in the Northern Territories (the four islands of Kunashiri, Etorofu, Habomai, and Shikotan), where Russia continues to exercise effective control.

Soviet troops occupied the Northern Territories after Japan accepted the Potsdam Declaration in 1945, and although most of them withdrew in the 1950s, large-scale military forces were again deployed in the 1970s. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the number of troops there has been greatly reduced, and all Russian troops have been withdrawn from the island of Shikotan. However, Russian forces are still stationed in Kunashiri and Etorofu. Moreover, since the 2010s, Russia has been moving forward with the qualitative modernization of its forces in the Northern Territories, and it cannot be ruled out that this will turn into a quantitative buildup in the future.

This article, therefore, will introduce recent developments in these military trends, analyze the intentions of the Russian side, and offer some proposals for Japan’s foreign policy toward Russia.

Overview of Russian forces stationed in the Northern Territories

Currently, Ground Force (SV), Navy (VMF) and Aerospace Force (VKS) units belonging to the Eastern Military District of the Russian Armed Forces are deployed in the Northern Territories. Russian Defence Minister Igor Rodionov, who visited Japan in 1995, put the number of troops there at “3,500”[1], and in 2011 an anonymous Russian Defence Ministry official was reported as saying the number would not exceed 3,500[2].

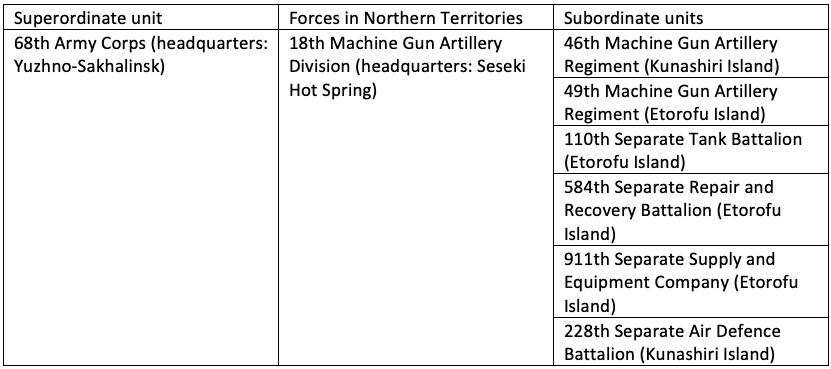

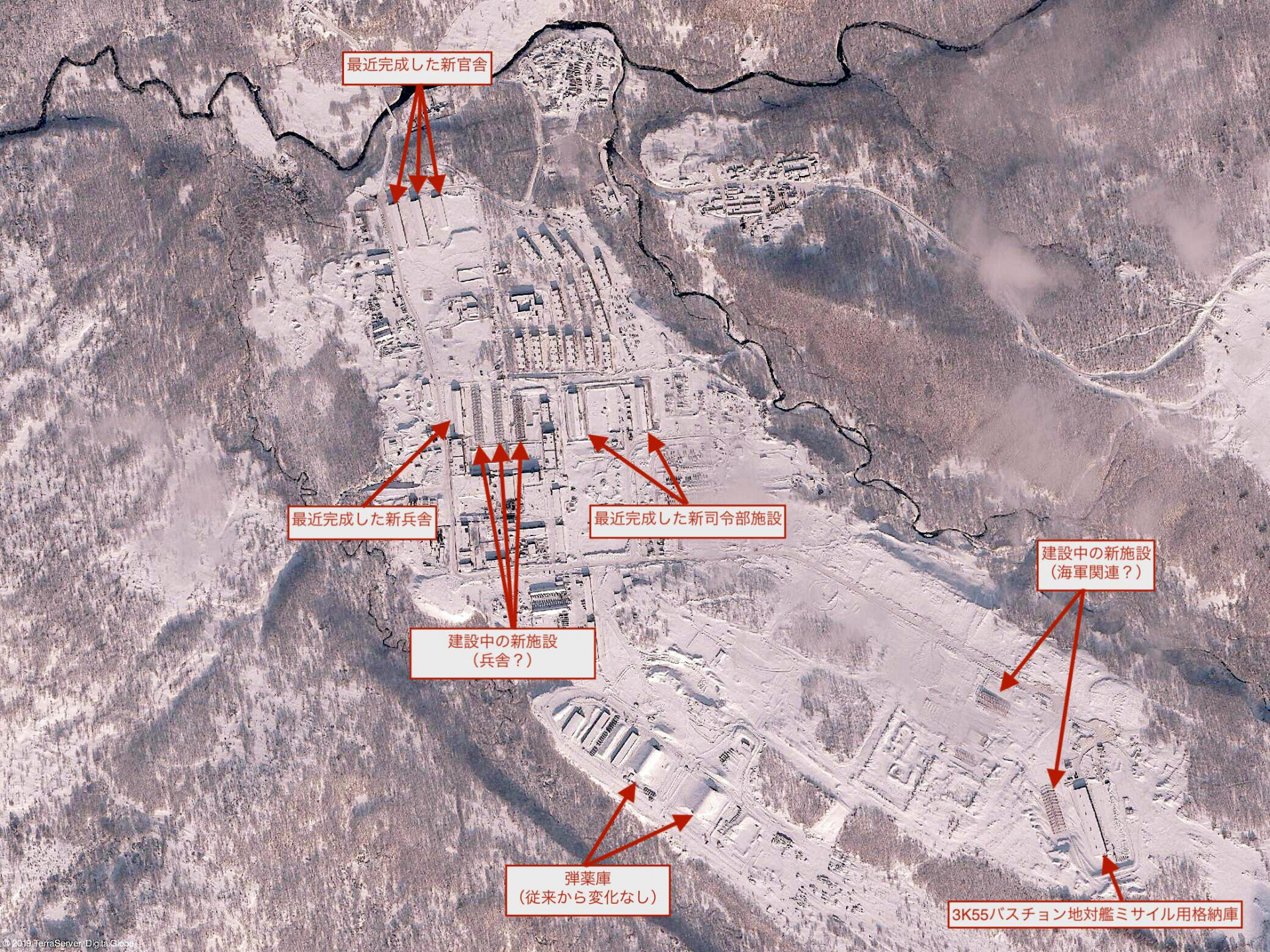

Of these, the main force is the 18th Machine Gun Artillery Division (18PulAD) under the 68th Army Corps (headquarters: Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk), with its headquarters at the Seseki Hot Spring (Russian: Goryachiye Klyuchi) in the central part of Etorofu Island. The Division’s order of battle has not been made public, but according to information from the Committee of Soldiers' Mothers of Russia, which works to protect the human rights of Russian soldiers, and other sources, as of the mid-2010s it was believed to be deployed on the islands of Etorofu and Kunashiri with a core of two regiments as shown in Table 1[3].

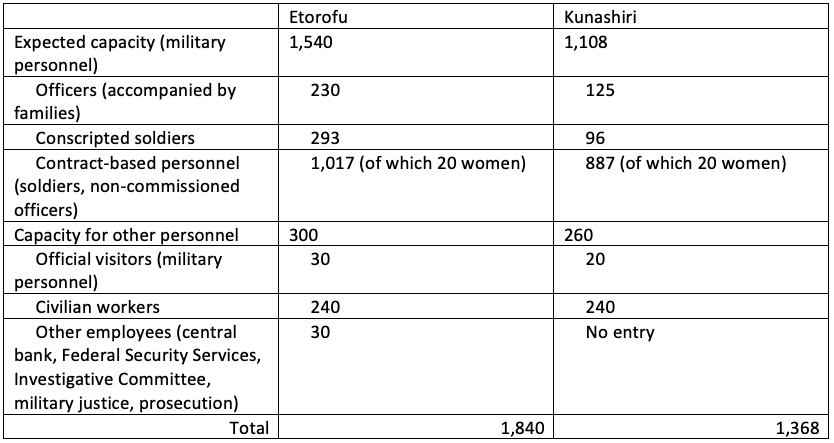

As far as can be determined by satellite images, Russia has not built any new garrisons or other facilities in the Northern Territories, so the number of troops deployed is not thought to have changed significantly. Additionally, in 2015 Russia’s Federal Agency for Special Construction, a part of the Defence Ministry, published a competitive tender notice online (now deleted) for the reconstruction of aging buildings and barracks on Etorofu and Kunashiri. Excluding officers’ family members, the buildings were indicated to have a total capacity of 3,208 people (Table 2). Including the personnel deployed to the Tennei (Russian: Burevestnik) Airbase and Yasniy Airport on Etorofu, which will be addressed below, the number of Russian troops stationed in the Northern Territories today is thought to still be about 3,500.

Status of modernization

Ground forces modernization

While the number of troops in the Northern Territories has not increased significantly, their modernization is gradually progressing.

In the army, the T-55, an outdated tank adopted in the 1950s with a 100mm gun, was upgraded to the T-80BV tank, which has a 125mm gun and gas turbine engine. Additionally, the Buk-M1 medium-range air defense system was deployed as a cruise missile countermeasure[4], and the Tor-M2U field air defense system was deployed in 2015[5]. Furthermore, in October 2020 the newspaper Izvestia reported that the deployment of the T-72B3, a modernized version of the T-72, had begun[6], but it is not clear if this was to replace the aforementioned T-80BV tanks or if a new tank unit had been formed. The Orlan-10 unmanned aerial vehicle has also been deployed since 2019[7].

Graphic:

Recently finished new government buildings

Recently finished new barrack

Recently finished new command facilities

New facilities under construction (barracks?)

New facilities under construction (naval facilities?)i

Ammunition depot (unchanged)

Hangar for 3K55 Bastion coastal defense missiles

Increasing sea and air power

Many of the above were updates to existing obsolete equipment, but Moscow has been building up the air and sea power in the Northern Territories. First, Russia has been strengthening the navy’s surface-to-ship missile force. Previously, one battalion of the 4K44 Redut surface-to-ship missile system from the 520th Coastal Rocket Brigade, headquartered in Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky on the Kamchatka Peninsula, was dispatched to the Etorofu, but in 2016 this was replaced by the state-of-the-art 3K55 Bastion. While the Redut's means of engagement, the P-35 anti-ship missile, travels at about Mach 1.5, the P-800 Ornix launched from the Bastion moves at over Mach 2.5, and is said to be able to fly at lower altitudes and penetrate enemy air defenses. At the same time, Moscow also deployed the 3K60 Bal on Kunashiri, which previously had not hosted any surface-to-ship missiles[8]. The Bal has the capability to simultaneously launch a number of Kh-35 Uran subsonic anti-ship missiles with a range of 130 kilometers, and together with the Bastion, which can control large areas, it greatly enhances Russia’s denial capability in the area near Hokkaido.

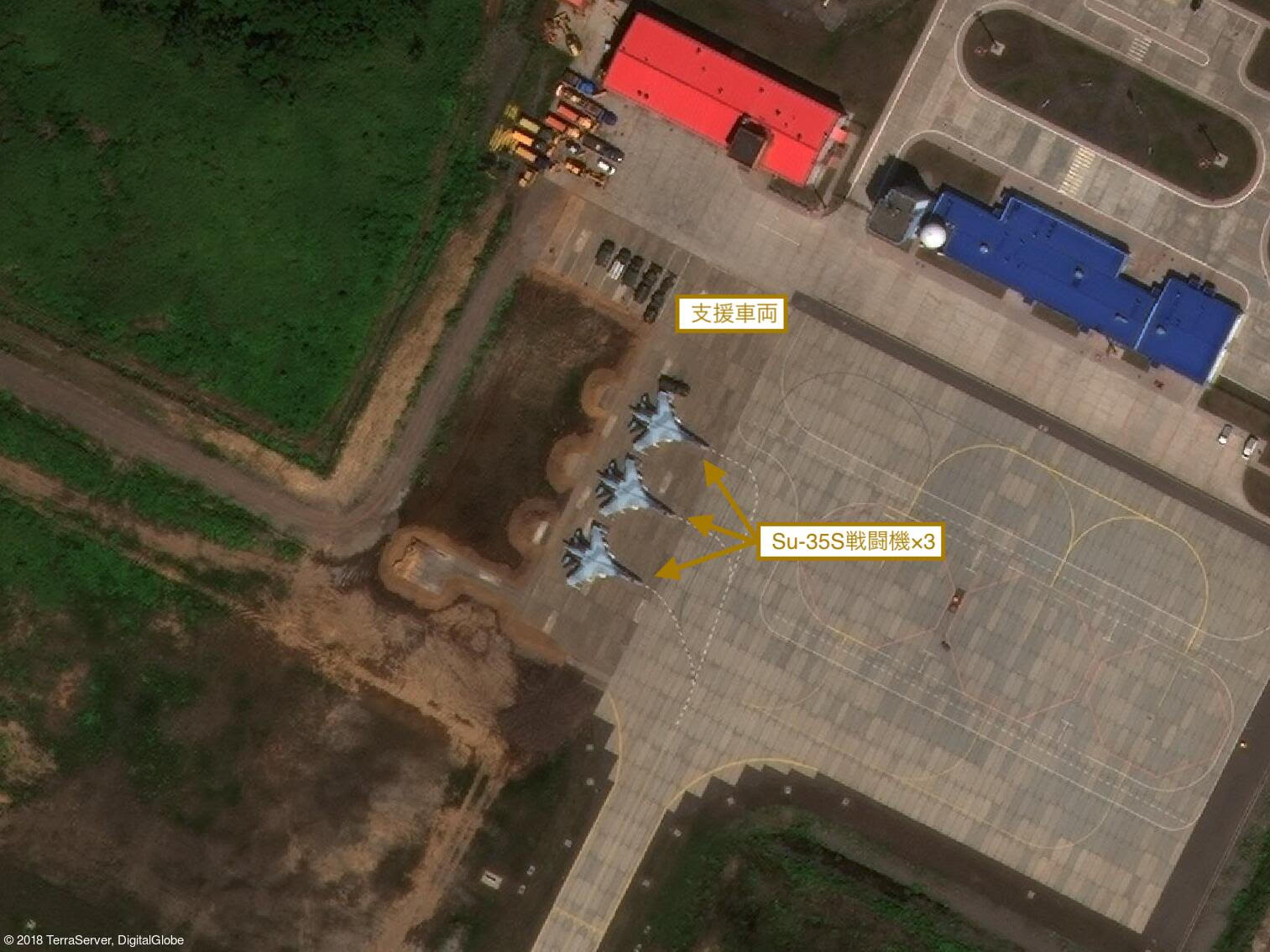

Furthermore, in August 2018 local media outlet Sakhalin.info revealed that three Su-35S fighter jets had been deployed to Yasniy Airport in the northern part of Etorofu[9]. They are believed to have been dispatched from the 23rd Fighter Aviation Regiment (23IAP) based at Dzemgi AB near Komsomolsk-na-Amure. This was the first deployment of fighter planes to the Northern Territories in a quarter-century, after Russia disbanded the fighter squadron stationed at Tennei AB in 1993. Prior to this, in May, First Deputy Defence Minister Ruslan Tsalikov announced that Russia would establish an air-defense identification zone over Kunashiri[10], and the deployment of Su-35S fighters was likely in line with this.

Yasniy Airport does not have the infrastructure for large-scale fighter deployments (parking aprons, ammunition depots, etc.), which is why Russia is limited to just three Su-35S fighters. However, Colonel general Sergei Surovikin, Commander-in-Chief of VKS, has indicated that he plans to modernize the Tennei AB by 2023[11]. After that is completed, the possibility of a larger fighter force being deployed to the Northern Territories cannot be ruled out.

Most recently, the S-300V4 air defense system, which can engage with not only aircraft and cruise missiles, but also ballistic missiles, was deployed in December 2020[12]. It is thought to have been deployed to a concrete formation built next to Tennei AB, but its affiliation is unclear (it is believed to be detached from the Army’s 38th Air Defence Brigade or the 25th Air Defence Division of the Aerospace Forces).

Graphic:

Support vehicles

Three Su-35S fighters

Conclusion

In short, one can conclude that Russia is modernizing its existing forces in the Northern Territories while building up new naval and air capabilities, and the scale of these activities is likely to further expand in the future.

Russia has also been taking similar actions around the Sea of Okhotsk, and the modernization and enhancement of its military capabilities in the Northern Territories must be seen as a part of this. Militarily, the Sea of Okhotsk — adjacent to the Northern Territories — is considered patrol grounds for the ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) of Russia’s Pacific Fleet. Given Russia’s emphasis on its nuclear forces as a means of compensating for the inferiority of its conventional forces, and the growing importance of such forces as U.S.-Russia relations have grown more confrontational since the crisis in Ukraine, strengthening the military capabilities in the Northern Territories makes sense from a purely military perspective. In this sense, looking at every development related to military power in the Northern Territories as a “check against Japan” or a “move for effective control” may lead to misjudgments about Russia’s intentions.

However, there is also danger in trying to understand the above developments looking only at military considerations. Since the 2016 Nagato talks, Russia has repeatedly claimed that the return of the Northern Territories could result in the establishment of a U.S. military base there and the deployment of a missile defense system, which could undermine Russia’s nuclear deterrent. Shotaro Yachi, who served as the head of the National Security Council during the Abe administration, said that Russia eventually escalated this position to the point of insisting that all U.S. forces be withdrawn from Japan if Tokyo wanted to settle the Northern Territories issue and conclude a peace treaty[13]. Thus it seems likely that the modernization of the military forces in the Northern Territories is not only in pursuit of military objectives, but also diplomatic ones, such as splitting the Japan-U.S. alliance.

Japan must take certain considerations into account in its diplomacy with Russia because the military power in the Northern Territories is linked to Russia’s strategic nuclear deterrence. A technical solution to this could be the inclusion of a demilitarization clause in a peace treaty (i.e., no deployment of any military force in the Northern Territories, no stationing of foreign troops, etc.), but if Russia's true motive is to interfere in Japan's security policy by emphasizing its military concerns, then one must assume that such a clause would have limited impact. Considering the Abe administration’s stance in negotiations with Moscow, this Moscow’s real objective.

In this case, Japan’s strategy toward Russia may need to undergo a major shift from that of the Abe administration. Tokyo will need to prepare for a prolonged diplomatic battle over the Northern Territories and return to the position of insisting all four islands are subject to negotiation, and at the same time take a stronger stance on human rights in Russia in cooperation with Western nations. Stronger economic sanctions (e.g., restrictions on the provision of funds and technology to the energy sector, as the U.S. and EU have implemented), rather than the current formalities, could also be considered.

In short, the “dialogue and cooperation” that was the hallmark of the Abe administration’s Russia policy should be replaced with “dialogue and pressure.”

(2021/05/31)

Notes

- 1 From “Defense of Japan 2018.” This reference was removed from the 2020 edition.

- 2 “Армия и вооружение на Курилах,” Интерфакс, 2011.2.15. (Russian)

- 3 в/ч Южно-Сахалинск и Сахалинская область.; “Гости с Сахалина: 18-я ПУЛАД в составе сил вторжения,” InformNapalm, 2015.1.23. (Russian)

- 4 “Войска РФ на Курилах вооружились новыми ЗРК и танками,” Лента.РУ, 2011.10.12. (Russian)

- 5 “Подразделения ПВО на Курилах заступили на дежурство на ТОР-М2У,” РИА Новости, 2015.9.23. (Russian)

- 6 “До Курил на танке: острова усилят новейшими боевыми машинами,” Известия, 2020.10.28. (Russian)

- 7 “Курильские аэродроны: беспилотники защитят Дальний Восток,” Известия, 2019.4.8. (Russian)

- 8 “Ключи от неба,” Боевая вахта, 2016.11.19. (Russian)

- 9 “Истребители Су-35С заступили на боевое дежурство в аэропорту Ясный,” SAKHALIN.INFO, 2018.8.3. (Russian)

- 10 “Зона боевого дежурства ПВО появится на острове Кунашир к концу года,” Звезда, 2018.5.23. (Russian)

- 11 “Чтобы господство в воздухе оставалось за нами,” Красная звезда, 2020.7.3. (Russian)

- 12 “На Курильских островах на боевое дежурство заступили С-300В4,” Звезда, 2020.12.1. (Russian)

- 13 Shotaro Yachi, “Japanese Diplomacy during the coronavirus pandemic,” Koken, December 2020. (Japanese)