Introduction

North Korea has resumed the testing of new missiles in recent months, conducting a series of launches since September 2021. And in October, Pyongyang held an exhibition to showcase its latest arsenal of missiles, demonstrating its intent to strengthen national defense. North Korea’s rapid development of advanced missile technology has prompted the administration of Prime Minister Fumio Kishida to consider the option of acquiring strike capabilities against enemy bases[1].

In the following, I will analyze the series of missile tests since last fall and examine the security implications for Japan.

Overview

North Korean ballistic missile tests have posed a threat to Japan since the first successful launch of Nodong-1 in 1993. The number of test launches increased significantly after 2016, with 23 missiles being fired in 2016 and another 17 the following year, according to the Japanese Ministry of Defense. There was a respite in 2018, during the period of US-North Korean rapprochement during the Donald Trump administration, but after the February 2019 Hanoi summit talks ended in a stalemate, tests of short-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs) resumed in May—although to the extent they would not incur Washington’s ire[2].

In 2020, eight missiles were fired through March, but tests ceased abruptly thereafter, possibly due to the COVID-19 outbreak. In 2021, after firing two SRBMs on March 25, Pyongyang halted its missile tests for six months; this period of calm, though, was interrupted in September with launches not just of ballistic but of other missiles as well.

Long-Range Cruise Missiles

First, on September 11 and 12, North Korea conducted what the Korean Central News Agency claimed were successful test launches of long-range cruise missiles. The statement noted that the missiles traveled for 7,580 seconds along oval and pattern-8 flight trajectories above North Korean territory and territorial waters, striking simulated targets 1,500 kilometers away. The North Korean claim has not been confirmed by Japanese and South Korean military authorities, but the released photos indicate that the launches themselves did take place. In fact, North Korea is believed to have fired two cruise missiles on March 21, 2021, as well, but they were both of short range.

If this “cruise missile” really had a range of 1,500 km, it could reach almost all parts of Japan from within North Korea. Tactics to defend against cruise missiles are similar to those used against aircraft. They are harder to detect, though—requiring airborne surveillance aircraft with lookdown radar capabilities—since they have smaller radar cross-sections and can fly at very low altitudes. If fired simultaneously with ballistic missiles, detection, tracking, and interception would require a dual system of missile defense. Then Chief Cabinet Secretary Katsunobu Kato rightly expressed concern following the September tests, saying that if North Korea really did fire a cruise missile with a range of 1,500 km, this would pose a serious threat to the peace and security of the region surrounding Japan. It should also be noted, moreover, that unlike ballistic missiles, cruise missile launches are not in violation of UN Security Council resolutions.

Railway-Borne Mobile Missile Regiment

The cruise-missile tests were followed on September 15 with the launch of two SRBMs, which the Japanese Ministry of Defense reported had a range of about 750 km and an altitude of 50 km. At first, there was confusion over whether or not the missiles had fallen within Japan’s Exclusive Economic Zone—most likely because the missiles had an irregular trajectory, with the warheads taking a low-altitude parabolic trajectory (known as a depressed trajectory) and then pulling up to extend their range, making it difficult to predict where they finally landed. The Ministry of Defense later announced that the missiles did indeed fall within Japan’s EEZ in the Sea of Japan.

On September 16, North Korea announced that the firing drill was conducted to confirm the practicality of a railway mobile missile regiment. The Eighth Congress of the Workers’ Party of Korea in January 2021 noted that the regiment was created “to increase the capability for dealing intensive blows in a simultaneous and multiple way to the threatening forces in case of necessary military operations and to markedly enhance the capacity for coping with various kinds of threat in a more active way.” North Korea claimed that the fired missiles accurately reached “a target area 800 kilometers away” in the “East Sea of Korea.”

The missiles are believed to have been longer-range variants of the KN-23-class SRBM closely resembling Russia’s Iskander missile. The test was significant for its first-time use of a rail launcher, rather than a road-mobile transporter-erector launcher (TEL). The quasi-ballistic trajectory, pull-up capabilities, and low altitude of the KN-23 make the missiles difficult to intercept[3]. Their short range at present makes them unlikely to reach targets in Japan, but if North Korea succeeds in extending their range, they could become serious security threats in the future.

Hwasong-8 Hypersonic Missile

On September 28, North Korea test launched a Hwasong-8 hypersonic (exceeding five times the speed of sound) missile. After issuing a preliminary report, Japan’s Ministry of Defense made no follow-up report for nearly seven hours, and even then, made no reference to the specifications of the missile, prompting speculations that it was a new type of missile. The details eventually came from the South Korean Joint Chiefs of Staff, which announced that the missile had a range of less than 200 km and an altitude of about 30 km. The following day, Pyongyang itself announced that it had launched a Hwasong-8 hypersonic missile.

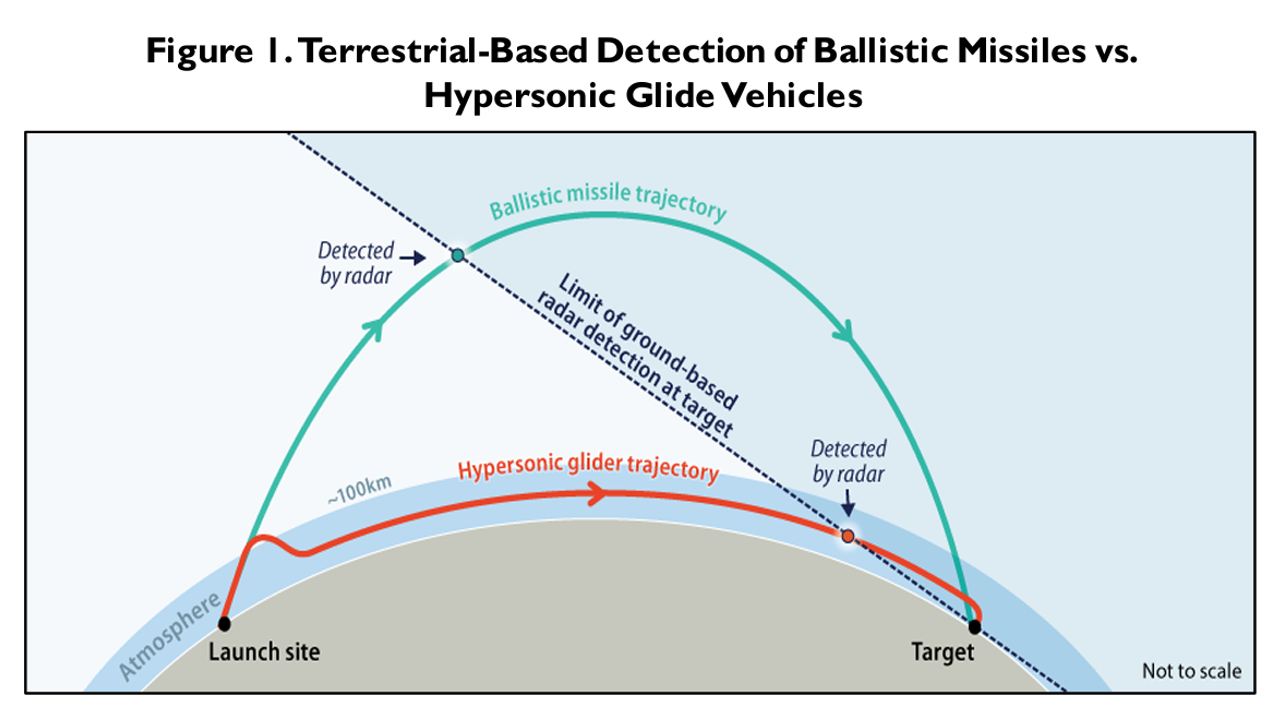

In the September 29 statemetnt, the KCNA noted that the test firing of the hypersonic missile was “one of five top-priority tasks of the five-year plan facing the field of strategic weapon for the development of defense science and weapon system set forth at the Eighth Congress of the Party.” It added that in this “first test-launch,” scientists confirmed the “guiding maneuverability and the gliding flight characteristics of the detached hypersonic gliding warhead” and “ascertained the stability of the engine as well as of missile fuel ampoule that has been introduced for the first time.” The description suggests that the Hwasong-8 is a not a hypersonic cruise missile (HCM), which requires the help of a high-speed scramjet engine to reach extreme speeds, but a hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV), which is launched into space on a ballistic trajectory, after which the warhead is released and glides toward the target at hypersonic speeds.

The latter, like conventional ballistic missiles, is initially powered by a booster rocket beyond the atmosphere, but the warhead, once it re-enters the atmosphere (at around 100 km), can ascend or descend, gliding along at low altitudes at hypersonic speeds[4]. The trajectory is unpredictable, making them nearly impossible to intercept with currently operational missile defense systems[5].

The September firing of the Hwasong-8 can hardly be called a success, though, and some time will be required before the missile becomes deployable, such as by extending its range. That said, we need to recognize that the North has been developing its missile technology at a surprising pace and is already capable of test firing a hypersonic missile.

Defense Development Exhibition “Self-Defence-2021”

North Korea showed off its missiles the following month not through test launches or a military parade but in the form of a defense exhibition. The display of Pyongyang’s latest missiles, called “Self-Defense 2021,” was held to commemorate the seventy-sixth anniversary of the founding of the Workers’ Party of Korea, with Kim Jong-un himself delivering a commemorative speech. This was a closed event, attended only by senior officials, rather than being open to arms traders from around the world. The aim of this unusual format is unclear, but the exhibit was no doubt aimed at boosting national prestige and sending a message to other countries, notably the United States.

Many of the missiles that North Korea had recently announced or launched were on display, including the new Hwasong-17 intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) mounted on an 11-axle TEL—which appeared in the October 2020 military parade—Hwasong-15 ICBM, Hwasong-8 hypersonic missile, Hwasong-12 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM), a ballistic missiles of unknown type, Pukguksong-4 or 5 submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM), Pukguksong-1 SLBM, a new type of SLBM (see below), KN-23 along with a modified type, KN-24, KN-25, an unknown cruise missiles, and a new type of anti-aircraft missile.

The fact that new or previously unknown missiles, such as the Hwasong-17 and Hwasong-8, were on display suggests that Pyongyang was eager to demonstrate it was actively developing new missile systems and to keep unfriendly nations in check.

New Submarine-Launched Ballistic Missile

On October 19, in the midst of the defense exhibition, North Korea tested a new type of SLBM from the port of Sinpo in South Hamgyong Province, said to be the base of North Korea’s SLBM-equipped submarines. The Japanese Ministry of Defense initially announced that two missiles were fired, with one flying for about 600 km on an irregular trajectory and reaching a maximum altitude of about 50 km before falling outside of Japan’s EEZ in the Sea of Japan. The ministry subsequently reported on November 9 that the second missile was a false detection.

The North Korean announcement of the “successful test launch” came the following day. Observers had speculated on whether the launch platform was a submarine or an underwater barge, but the statement noted that it had test-fired a new type of SLBM from the 8.24 Yongung, the ship that that launched North Korea’s first SLMB in 2016. This indicates that the launch was not from the new 3,000-ton submarine being developed by modifying a Soviet-era Golf-class submarine but from a Gorae/Sinpo-class 2,000-ton class submarine. The Japanese government said it presumed the missile was launched from a submarine. Japan’s current ballistic-missile warning, monitoring, detection, and tracking system assumes that launches are made from within North Korean territory; should Pyongyang acquire submarine-launch capability, Japan would need to review its missile defense posture by monitoring a much broader area[6].

North Korea’s earlier SLBM launches were of Pukguksong-1 and Pukguksong-3, which are medium-range ballistic missiles (MRBMs) with a range of over 1,000 km. And while larger and longer-range missiles like Pukguksong-4 and Pukguksong-5 have been shown at military parades, they have yet to launched. The missile fired in October 2021 had a shorter range of around 600 km, and its warhead had an irregular trajectory similar to that of the KN-23. The missile could thus have been a new type of SLBM incorporating KN-23’s maneuvering technology[7].

It is believed to have been the smallest of the three SLBMs on display at the Self-Defense 2021 exhibition, shown alongside Pukguksong-4 and Pukguksong-5.

How North Korea intends to utilize the new missile is still unclear. SLBMs are generally regarded as reliable second-strike (counterattack) weapons after suffering a nuclear attack. As a rule, therefore, SLBMs are tipped with nuclear warheads, and they need to have a long-enough range to reach the target country. Pyongyang’s technical prowess in miniaturizing nuclear warheads and launching them from submarines will thus bear close watching. Given the irregular trajectory taken by the warhead in October, there is an urgent need to enhance the preparedness of Japan-US missile defense.

Conclusion

The above is an overview of North Korea’s test missiles launches since September 2021. Their features can be summed up as follows.

First, they have basically been short-range missiles of up to 1,000 km since May 2019[8]. This may be because Pyongyang is already confident of its ICBM technology after successfully firing Hwasong-15 in November 2017 or because it believes—on the basis of the series of US–North Korean summits—that short-range launches would not elicit a strong reaction from the United States[9].

It is therefore likely to continue testing shorter-range missiles with progressively advanced technologies, such as hypersonic and cruise missiles that, like the KN-23 warhead, have irregular trajectories[10].

Pyongyang’s intentions seem to be to develop and verify technologies capable of slipping through the missile-defense system that Japan, the United States, and South Korea have put into place. As mentioned above, intercepting a KN-23 would pose a major challenge, and the same goes for hypersonic glide vehicles and SLBMs. If North Korea were to possess such a technology, Japan, the United States, and South Korea would be forced to fundamentally rethink their missile defense system.

※Translated from an article originally published in Japanese on November 22, 2021, and does not include references to subsequent test missile launches by North Korea.

(2022/04/18)

Notes

- 1 The ruling Liberal Democratic Party’s platform, for example, calls for new initiatives to enhance deterrence against the heightened military capabilities of neighboring countries and to respond to security contingencies, such as by bolstering ballistic-missile defense and acquiring the capability to intercept missiles within the territory of the hostile country.

- 2 SRBM tests should not be overlooked as long as ballistic missiles are involved, since they are in violation of UN Security Council resolutions, but the Trump administration paid little attention to such launches, as they did not pose a direct threat to the US mainland. The administration has been criticized for failing to correctly recognize the scope of the Security Council resolutions.

- 3 Of the two systems of missile defense, the SM-3 interceptor cannot hit targets flying at an altitude of lower than 70 km, while the PAC-3 is unable to reach missiles traveling higher than 30 km.

- 4 The missile’s trajectory before the warhead is released is similar to that of a conventional ballistic missile, though, so interception may be possible during the booster phase or, depending on the maximum altitude, during mid-flight.

- 5 Other hypersonic missiles include Russia’s Avangard, 3M22 Zircon, and Kh-47M2 Kinzhal; China’s DF-17; the US Navy and Army’s Conventional Prompt Strike (CPS)/Long-Range Hypersonic Weapons (LRHW); and the Air Force’s AGM-183 Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon (ARRW). Japan has stated its intentions to develop hypersonic technologies as part of an effort to achieve standoff capabilities.

- 6 Japan will need to defend against surprise attacks if the location of submarine launchers cannot be determined. North Korean submarines are relatively easy to detect due to their noise, but the need to track them would become an additional burden on Japanese forces.

- 7 The North Korean statement claimed that a number of advanced control guidance technologies were introduced, including flank mobility and gliding skip mobility. The November 9 Ministry of Defense announcement, though, maintained there were no indications of flank mobility.

- 8 The Pukguksong-3 SLBM launched on October 2, 2019, on a lofted trajectory reached an altitude of about 900 km and had a range of about 450 km. If fired on a standard, minimum energy trajectory, the missile is thought to have been capable of traveling over 2,000 km.

- 9 North Korea has not been neglecting to develop ICBMs, though, as evidenced by the new Hwasong-17 mounted on an 11-axle TEL that was unveiled at the October 2020 military parade.

- 10 Because cruise missiles launches are not banned by UN Security Council resolutions, Pyongyang appears to believe that it can test such missiles with long-range capabilities.