- ISSUES IN PEACEBUILDING

Democracy in Post-Conflict States in Africa: Is the “Gospel” of Peace Undermining Democracy in Eastern Africa?

Introduction

Political strife traverses the eastern region of Africa, and the region commonly referred to as the “horn of Africa”. Sometimes, such cases of strife have resulted in violent bloodshed, and have been difficult to stop. Thus the region is dominated of several countries, which have experienced, are experiencing, or are recovering from armed conflict. These violent strifes can be blamed on myriad of factors ranging from resources to an agitation for democratic space. The commentators of security issues in the region have also pointed fingers at sectarianism and identity politics to explain presence of violence in political strife. The few countries that have emerged with strength from such internal conflicts in the region did so because of better institutional arrangements for democratic governance.

Some countries in the region have had persistent waves of violence that threaten, not only local political order, but also the entire region. In particular, the persistent unrest in Somalia has brought the region particular significance in the global security discourse. This concern has led to, in part, the insurmountable efforts to ensure that peace prevails in this region at all costs. Thus some states have become a hub for investment and focus in efforts to build peace and avert any form of civil unrest. This pursuance of peace is often ambivalent. Thus, while the achievement and sustenance of peace in Rwanda is some sort of a diplomatic miracle to be celebrated; a country healing from devastating genocide to achieve not only peace but also economic prosperity, this peace has been executed on the altar of sacrificing democracy and justice. Thus, Rwanda’s Paul Kagame seems to enjoy the freedom to manipulate democratic processes and intimidate people and to make institutional adjustments to consolidate his power while silencing his political opponents and any voices of dissent.

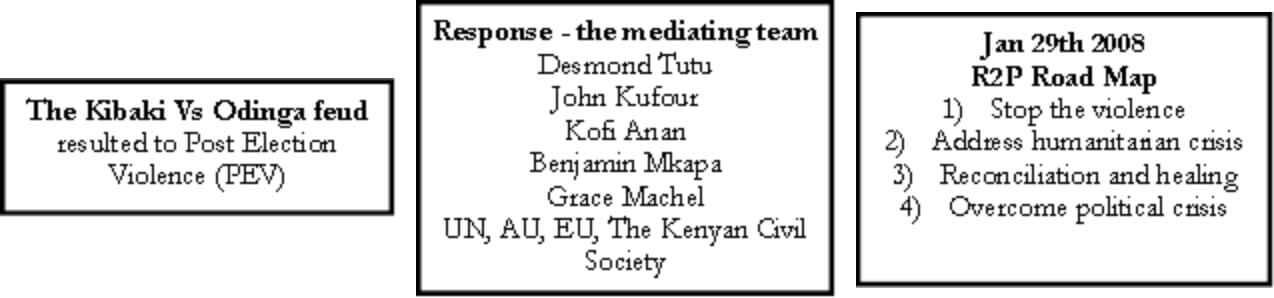

Just as Rwanda provides a platform that proves how a country can successfully overcome a deadly violence and adopt institutions that aid substance of both good governance and economic growth, Kenya as well offers an example of how a country can, not only overcome strife but prevent internal conflicts from escalating into large scale ethnic wars which are often hard to recover from. In this regard, Kenya overcame a short-lived threat to its reputation of stability and mature democracy in the region in the late 2007 and early 2008 when a widespread Post Election Violence (PEV) hit most parts of the country after a disputed general election. After a successful bridging by the local efforts in collaboration with the international community, the stature of Kenya was restored with difficulties. Based on the crucial role of Nairobi in the region with several dysfunctional governments to foster peace and security in the region, it is imperative to focus on how the peace discourse can usually yield unintended results, or in other words how an overemphasis on the discourse of peace can hinder necessary reforms and building of institutions that have the capacity to foster long term assurance of peace, posterity, and prosperity.

In the periods leading up to the 2013 and 2017 general elections in Kenya, there were concerted efforts by the local and the international community emphasising peace during the political competition for votes. This pervasive peace narrative may have delegitimised political activities feared to hold enormous potential to political instability.[1] This article explores how the coalition of local organisations and their counterparts in the West is undermining democracy in Eastern Africa though supporting the pursuance of peace at whatever cost, and emphasising that peace should be prioritised even at the expense of justice. The local peace crusaders, especially the local church, media, and the civil society have adopted this particular through a normalisation of the perception that the voices of dissent by the opposition, especially in its calls for protest is an embodiment of chaos. The peace narrative is seen to be encouraging enthronement of tyrants through the ballot exemplified by the landslide wins of Kagame and Kenyatta of Rwanda and Kenya respectively. While praise on strands made by the peace narrative in stabilising the region is necessary, it is perhaps time to move away from the phobia inspired by volatility of societies in East African region. It is time to focus on strengthening democracy, ensuring administration of justice and create the sense of inclusion to the already disenfranchised majority.

Complications for Peace Building and Democracy Emerging from “China in Africa”

Conflicts in Africa are generally perceived to stem from the failure of governance structures and lack of stable institutions that can mediate conflicts when they arise. Furthermore, there is also a lack of institutional capacity supportive of a stable democracy hence creating a possibility to avert conflicts altogether[2] on the one hand. On the other hand, Africanist literature[3] does not seem to emphasise the element of conflicts resolution that usually erode the prospects of strengthening democracy and administration of justice.

Conflicts in Eastern Africa seem to contradict and defy Tilly’s[4] idea that, “war made the state and the state made war.” Against Tilly’s theorisation, conflicts in this region have yielded negative consequences. Scholars concerned with this aspect of negative consequences of conflict on state building[5] have not delved into an important aspect of conflicts management’s impacts on the advancement of the democracy in the region. Since most of the states in the region have managed to emerge out of conflicts successfully, it is important to emphasise the post-conflict state building process. This aspect is even much more intriguing in countries like Kenya where the duration of the conflict was notably short. In this regard, the institutional capacity to enhance democracy is crucial especially in the view that “pro-democracy foreign powers are more likely to accept poor quality elections in post-conflict countries, in part because they fear that adopting a tougher stance might result in resurgence of war”[6].

Although democracy is alive in Africa, it is not thriving, especially for those states struggling with the peace building process. The fruit of the democratic decade (1990s) in Africa is therefore rotting even before it is ripe for harvest. Perhaps blame towards African leaders’ laxity in furthering democracy in the continent is a limited explanation. One particular way to account for laxity in pursuit of democracy is analysing the manner in which the seed of democracy was planted. The 1990s political reforms relied heavily on strict economic policy reforms imposed on the African governments. Furthermore, democracy was also promoted within the strong urge to carry out constitutional reforms.

This foundation on which democracy was anchored by the West protagonists has been fiercely challenged by the value-neutral “no strings attached” diplomacy of China whose presence in Africa is outwitting that of the West. China has become the strongest supporter and partner of Africa since 2009. In response to the Chinese presence in Africa, the West seems to be abandoning its commitment to Tony Blair’s “ethical foreign policy.” Thus, out of the fear of further loss, the West’s commitment to democracy in Africa seems to be dwindling.

In the place of democracy, there has been an emphasis on stability and peace. Electoral and other forms of justice are overlooked, and left to the hands of local leaders for local solutions as long as stability and peace is perceived to prevail. Thus, the West has resorted to preaching peace, while abandoning the brut demands for political reforms that were an emphasis of the 1990s. The Chinese apolitical diplomacy and the passive Western approach have deflated the wheels of democracy. Thus, Africa has been experiencing an expanded capacity for economic development partnership without major demands for reforms on the one hand. On the other hand, the ground on which the international community could use to demand reforms has been shrinking. Thus, unlike in the West Africa, specifically Nigeria and Ghana where the incumbents were trounced in an election and handed over power peacefully, the Eastern Africa region is experiencing what Mkandawire has identified as “choice-less democracy.” While peace is a fundamental pillar of prosperity, to many African nations, it is perhaps important to begin accounting for the cost of the Chinese presence in Africa that is making the West bargaining power in the continent weaker.

Implementation of Peace Building Model in Kenya: The Responsibility to Protect (R2P)

When Rwanda experienced its darkest moment in history in 1994, the international community was condemned for failure to intervene so as to prevent escalation of ethnic uprising. In this regard when Kenya, a country whose fragile ethnic composition has striking similarity with Rwanda, displayed early signs of going the Rwanda path in 2007/8, both the local and the international stakeholders were swift to act.

Post Election Violence (PEV) in Kenya

The 2007/8 violent episode in Kenya can be said to be the climax of various other ethnically charged violence during the previous electoral seasons. The re-emergence of multi-party democracy in 1992 created uncertainty for the then ruling elite possibility to continue holding onto power. To ensure that they continued their grip on power, President Daniel Arap Moi led party instigated ethnically based clashes in attempts to intimidate residents of particularly opposition strongholds not to participate in voting. These clashes recurred in 1992 and 1997. It is only 2002 when a coalition of two tribes, the Kikuyu led by Mwai Kibaki and the Luo led by Raila Odinga, joined hands that ethnic clashes were not witnessed. The 2007 clashes were the most tragic and violent. The violence was triggered by the Electoral Commission of Kenya (ECK) announcement of Mwai Kibaki as the winner of December 27th 2007 election against his rival Raila Odinga. The conflict that arose following the announcement claimed 1,500 people and displaced at least 500,000 others in a conflict that was characterised by attacks of political rivals of different ethnic groups. These often election related violence that have taken place in different locations in Kenya thrive on a politicised ethnicity that appeals to ethnic constituency to seek means of ascending to power.

Necessity for the Responsibility to Protect (R2P)

The lessons from the 1994 laxity on the side of the international community to respond to Rwandan genocide spurred a wide-ranging condemnation due to the failure to act. The Rwandan crisis was as a result of negative use of ethnic capital. Thus, in early 2008 when communities allied to different political camps rose against each other out of disputed elections in Kenya, the international community had the foundation for a moral need to nip such atrocities at their earliest stage. The unexpected uprising 2008 seemed like an inevitable downfall of one of the beacon of peace and economic prosperity in Eastern Africa, and the horn of Africa at large. The international community did not let Kenya slide into the precipice of disaster. Instead, the reports appearing on the media prompted action from the prominent members of the African Union (AU), the United Nations (UN), and the European Union (EU) who partnered with the civil society in Kenya to facilitate negotiations for peace.

Since the 2007/8 conflicts had risen to the level of crime against humanity according to the International Criminal Court (ICC), actors involved invoked R2P, of which Kenya had ratified during the 2005 UN World Summit. R2P as a practice has three main pillars;

(1) Prevention

(2) React in the eye of mass atrocity storm

(3) Rebuild after the storm

R2P also is focused on an emphasis that;

(1) It is not only the military intervention that matters

(2) Sovereignty is contingent upon basic respect for human rights

(3) Emphasises on prevention

Through actions that illustrated R2P in operations, the immediate action was done through appealing to the political will of the two opposing sides, Mr. Mwai Kibaki who lead the Party of National Unity (PNU) and Mr. Raila Odinga who headed the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM). The process paid off when the two party heads agreed to share power in a coalition government that lasted from 2008 to 2013.

The efforts to avert disaster guided by R2P principles were largely successful. However, as Kofi Anan foundation observed, the process of the implementation of the agreed agendas was ineffective and slow, causing fears of a possibility of similar violence erupting. This notion is evident in the tensions that have persisted during 2013 and 2017 general elections, showing that the root causes of the violence (negative ethnicity) were not fully addressed.

Based on the concerted efforts to prevent the escalation of 2008 violence surging to uncontrollable scales the efforts to maintain peace spearheaded mainly by the international community in conjunction with the Kenyan civil society has since then been vigorously been pursued in the two elections that have been held after 2007 in 2013 and 2017. These peace crusades seemed to be inspired by a genuine fear that if enough mobilisation is not done, violence of much greater scales than that of 2007/8 was more likely to re-appear. The specific character emerging out of the good efforts that have focused on peaceful elections usually accounted for by the absence of violence have overlooked the necessity of credible electoral process that has much bigger potential to foster not only peace but also faith in the democratic process and its institutions in Eastern Africa and Africa at large.

The 2013 and 2017 Elections: Confronting the Ghosts of 2007/8

The crimes perpetrated in 2007/8 were shocking to both the Kenyans and the international community. The primary concern and the probably the primary cause of the 2007/8 violence was a claim that the elections were manipulated in favour of the incumbent. A few days into the votes counting the opposition leader was ahead of the PNU candidate. Several days of waiting eventually allowed the hand of the executive to intervene coercing the ECK to announce Mr. Mwai Kibaki as the winner. It is only after this announcement that violence broke out. It is easy to label this violence ethnic, especially if one follows the pattern that they took. Violence erupted mainly in ethnic “hotspots” where one ethnic group has been historically disenfranchised as opposed to places where homogeneous groups had lived for several years together. Thus, such areas as Kibera, Mathare, and the Rift Valley were most affected by the violence. The Kiambaa church in Eldoret, which was, attacked after a group of Kikuyu migrants sought refuge in it is particularly revealing of the nature of 2007/8 violence. The name Kiambaa was transplanted from Kiambu in central Kenya. After taking over the land previously occupied by the Kalenjins, the Kikuyu migrants eventually adopted the name that would remind them of their ancestral land in central Kenya. In this regard, the 2007/8 PEV was also a display of dissatisfaction in a political agitation for “restoration” and rights to land that was swept under the carpet over the years. On the other hand, the protests that took place in the Nyanza region, and an absence of violence in the central Kenya region manifests an expression of dissatisfaction of a community with the political arrangements to access power. The Nyanza region was protesting the denial of their “turn to eat”[7] since their man was almost clinching the presidency. The central Kenya community on the other hand had nothing to fight against, since the assurance of them remaining in power was rubber-stamped by the electoral commission.

The 2008 R2P pact has achieved notable significant steps toward achievement of stability such as the inauguration of the new constitution in 2010. However, this pact has not succeeded in addressing what these communities agitated for, that is, a democratic process that guarantees accessibility to rights to share in the national cake. In this regard, it is important to be concerned with the manner in which the peace brigade is succeeding in sweeping the urge for a democratic space under the carpet, or precisely the ethnic tensions. Ethnic relations in Kenya are the most easily accessible tools for political agitation, both by the political elite and the masses. While the political class uses ethnic capital to gain access to and ascendance to power, the masses may coordinate within the ethnic capital to mobilise for a voice in political contestation.

Despite the successful efforts that halted the eruption thus preventing a prolonged ethnic based violence, the fragile situation inspired fears as the country approached the 2013 elections. Furthermore, the politicisation of the justice process pursued through the ICC, sparked more fears of a possible conflict if president Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy William Ruto were charged with the crimes against humanity. These fears were quenched when the dissatisfied loser, Mr. Raila Odinga, opted to go to court after claims of electoral malpractices thus averting a crisis that could have been precipitated by civil protest. While accepting the verdict of the supreme court to uphold the declaration of Uhuru Kenyatta as duly elected by the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC), Mr. Odinga pointed out that “Although we may not agree with some of its findings, and despite all the anomalies we have pointed out, our belief in constitutionalism remains supreme. Casting doubt on the judgment of the Court could lead to higher political and economic uncertainty, and make it more difficult for our country to move forward.”[8]

The decision by Odinga to seek judicial justice rather than invoke the right to picket and protest enshrined in the constitution has two dimensions. First, it showed that there was an advancement made to restore faith in institutions that are vested with the responsibility to safeguard democracy unlike in the 2007/8 case when the then president friendly court could not be trusted to be impartial. Secondly, Odinga was surrendering to the imminent pressure not to call for civil disobedience spearheaded by the narrative of peace, as it was feared to be amenable to spark violence. In this regard, the role of peace narrative in 2013 and 2017 electoral seasons can be said to have been successful to some degrees, especially if the absence of major reports of violent acts is attributed to the peace campaigns. Unlike R2P, which takes measures against possible escalation of violence, hence striking a possible political solution like the one of 2008, the peace crusades’ success is only measurable through the absence of violence. Absence of violence is often seen as a sign that there was a peaceful electoral process. But to what extent are the silences, and acquiescence a reflection of efficient democratic methods and arrangements that facilitate leaders democratically elected to occupy political positions? Despite the prevailing peace that characterised the 2013 and 2017 elections, several factors lead to questions about the credibility of electoral process, which in-turn cast doubts into the democratic space in the East African nation.

Pursuance of R2P in Post 2008 Kenya

One of the greatest achievements from the agreement of 2008 pact was inauguration of the new constitution in 2010. The 2010 constitution significantly reduced the power of the president who under the centralised presidency enjoyed unlimited powers. It as well ensured an implementation of a system of governance that veered away from the highly Nairobi based centralised governance by decentralising structures of the central government to the county levels overseen by the elected governors and Members of County Assemblies (MCAs). This seemed amenable to curb the inequitable development that usually favoured a single community whose their man was in power in the practice of the kinds of politics called “its our turn to eat”[9]. Besides the constitutional change, there were other import initiatives that were rolled out. Such initiatives include the following.

a) Media and Mobile Phone Technology’s Role in Spreading the Message of Peace

One of the findings by Waki commission[10] was that the inflammatory language triggered part of the causes of violence in the run-up to and in the aftermath of the election. This report implicated radio stations, most of which broadcast to particular ethnic communities in vernacular, as responsible for inciting tribal allegiance and conflict. Besides the media, ethnic tensions were also raised via mobile phone short messages services (SMS) sent by anonymous groups either seeking support or mobilising against communities.

The Waki commission recommended media reforms to curb misuse of what have become almost uncontrollable vernacular stations in their role in spreading hate and animosity. Thus the state in response established the National Cohesion and Integration Commission (NCIC) that was mandated with facilitating peaceful coexistence among ethnic groups with a specific role to control spread of hate through media. Thus the goal to promote coexistence in elections by NCIC has been attained through media regulation, but was also facilitated by a specific campaign urging people to resist violence and embrace peace through negating ethnicity and embracing nationhood. As a result, the media in 2013 and 2017 has not been an instrument of hate, although a deeper analysis still indicates tribal bias in most of the vernacular stations. The role of media in both 2013 and 2017 electioneering periods has been hailed as having had a critical role in reducing tensions among ethic groups. Krieglar report of 2008[11] had shown that the particular media houses had shown support and preference for candidates in 2007 while announcing unverified unofficial presidential results. In contrast, the media in 2013 constantly called for calm and send out messages of peace even when results were delayed[12]. In 2017, the announcements of presidential results were further delayed as the media stations could announce only the tallying transmitted by the IEBC.

b) The Grassroots Initiatives for Peace

The efforts of NCIC to tackle the problem of hate speech has become complicated as most people had adopted the social media platforms such as twitter, Facebook, instagram, and whatsapp in the run-up to the 2013 and 2017 elections. Thus, the success of monitoring SMS through a mandatory registration of all sim cards between June 2010 and November 2012 faced a new challenge in form of social media platforms. The challenges emerging from new social media platforms have however catapulted a development of new platforms that supported and expanded platforms to urge people to embrace peace by the civil society and the international donor community. The Ushahidi and Nipe Ukweli[13] were among the most notable platforms used to spread the messages of peace while countering hate speech at the same time. Religious organisations also became vocal in urging communities to forsake ethnicity and nationhood.

The NCIC in partnership with the UNDP established district based peace committees that focused on spreading the messages of peace, training peace monitors, and offering public education on conflict and dispute resolution during election period. The national steering committee on peace building and conflict management that was composed of the state and civil society representatives focused on conducting peace forums on conflict prone zones such as the Rift Valley, Coast, and Eastern[14]. Similar other initiatives included Amani Kenya, Tia Rwambe, and sports for peaceful elections campaigns[15]. There were also other local peace initiatives overseen by PeaceNet under the Uwiano platform[16].

The Cost of Peace: Mugged Media, Disintegrated Civil Society, and the 2 Elections in 2017

The vigorous peace campaign has with no doubt helped Kenya navigate peacefully through two general elections since the disputed one in 2007. However, the alliance for peace seems to have crippled the vital institutions that ensures a thriving democracy in which the two most affected intuitions are the civil society and the media thus the cost of peace has been a negligence of electoral reforms that ensures a democratic process where the voices of the people are heard and reflected in the election results.

The victory of Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto in 2013 was controversial in two basic ways. At home, the local courts had declined to declare them unfit to run for public office based on Article 6 of the Kenyan constitution that bars individuals tainted with unethical conducts from holding a public office. On the international stage, the president and his deputy were needed to answer to charges of crime against humanity as a result of being indicted by the ICC as perpetrators of 2007/8 PEV. ICC became a highly politicised issue that threatened the credibility of ICC altogether.[17]

The confidence gained after garnering access to state house win inspired Kenyatta and Ruto to mobilise the African states against the Rome statue. Kenya was successful in securing a communique from the African Union (AU) that could facilitate a mass withdraws from ICC by the African states in 2013. These efforts were supported by the Kenya National Assembly, which voted to withdraw from the court in the same year. These kinds of efforts were followed by claims of interference with the ICC justice process. By the time crucial witness was supposed to be made, most of the witnesses had withdrawn citing intimidation by the state.

The intimidation of the witnesses was not received well by the civil society who were generally supportive of the ICC process. The state, through both the conventional and particularly the social media vilified the civil society naming it the “evil society”. The animosity between the state and the civil society has culminated to a major crackdown on NGOs. Towards the run-up to the 2017 elections, NGOs perceived to be friendly to the opposition were threatened with de-registration and disbandment, an example of this being the Africa Centre for Open Governance (AFRICOG)[18].

Although Kenya has enjoyed the reputation as being one of the countries with the freest media in Eastern Africa region, this reputation is being put to test and is at risk. While the media, through a focus on peace, tranquility, and calm may have averted an occasioning of the violence caused by the incitement, this passive positioning of those who are charged with the responsibility to be public watchdogs raises serious questions on the growth of democratic space. When Odinga raised concerns regarding irregularities on ballot counting[19] the media was quick to urge him to move to court if he was dissatisfied. Some have argued that journalists themselves were hoodwinked by the message of peace[20]. When Odinga moved to court, this kind of passivity seemed to persist. Thus, the message of the media to Odinga and the opposition at large was seen to be in harmony with that of the ruling Jubilee party; that Odinga should accept the results and the verdict of the courts and move on. This urge to move on did not account on how the purported claim to vote manipulation would be dealt with, or even attempt to establish its validity. The most crude form of intimidation of media was in reposes to journalists’ defiance to the state’s instruction not to live stream the mock inauguration of the opposition leader as the “people’s president” in January 30th 2018. On this day, the leading broadcasting houses (NTV, KTN, and Citizen) were pulled off air and some of their journalists threatened with jail term.

Three key promoters of democracy in Kenya since 1992 have been religious organisations, the civil society, and the media. These organisations were instrumental to making of the new constitution that facilitated Kenya to implement R2P. They also acted as major promoters of peace building in both the 2013 and the 2017 general elections. The mugging of any these institutions is perhaps out of the tyranny that the current ruling party (Jubilee party) enjoys in the control of both the senate and the national assembly. But it is also their own making. They have overlooked the need to encourage extensive electoral reforms and failed to encourage an introspect into historical injustices that have precipitated violence after almost every electioneering period since 1992 and instead thrived on the phobia created by the 2007/8 election violence. This phobia has driven them to spearhead, prescribe, and mobilise populations to embrace peace void of justice as a people of one nation thus also vehemently denying the radical reliance on tribal allegiance in political contestation.

The demons of 2007/8 that were exorcised through the message of peace in 2013 came to haunt the country in 2017. The 2017 contest was a rematch between Kenyatta and Odinga, with almost a similar line-up as that of 2013. The message of the media about peace still triumphed since the fears of sliding back to the 2007/8 incidents were still fresh in the minds of most Kenyans. Thus, the red flags to vote manipulations prior to Election Day on 8th August 2017 were not perceived as of grave concern. One such incident was the killing of the data centre and infrastructure manager of IEBC, Chris Musando, days before election. Similarly, there was no strong emphasis given to claims of hacking of electoral system made by the opposition party in the morning after August 8th election. Therefore, the annulment of the August 8th 2017 election by the Supreme Court came as a surprise to many. Odinga declined to participate in the fresh elections thus leaving only one candidate as a sole serious contender. As a result, Uhuru Kenyatta garnered 98% of votes, which has legitimised use of excessive force to intimidate his opponents.

Conclusion: the Decline of Democracy; Rise of Authoritarianism

Political expression in Kenya is seen as most advanced in the Eastern Africa region. However, there are elements that shows that although Kenya has made important strands on democratic space, there has been visible impediments to gains made which if not confronted threatens the demise of democracy. This article has analysed one such act that has unwittingly de-emphasised the pursuit of democracy and obscuring of justice as the promotion of peace by the international and local adherents. Although it has in part facilitated to most needed peaceful electoral process, it has also put the country at the verge of death of democracy and an ever-increasing normalisation of injustices.

In 2017, the most significant sign of this freedom was the institutional maturity shown by the supreme court after declaring the presidential polls conducted on 8th August 2017 null and void citing that the process was marred with irregularities and thus forcing the incumbent to go back to the camping for a fresh election. Although this step maybe hailed as a great step towards democracy, the response by the ruling party was that there is a need to regulate the democratic space, with some state officials openly calling for the head of state to be a “benevolent dictator”[21].

2017 elections revealed how myopic the Western election observers can be[22]. The nullified election on 8th August 2017 had been given a clear pass by the election observers who called it “free and fair.” This declaration was made despite the events prior to elections that put to question the credibility of the process. Furthermore, the observers were oblivious of the opposition claims that there was manipulation of votes through “hacking” of the electoral system. Thus, when the Supreme Court overturned the elections, it became a time for self-reflections for many, especially the international observers who had given the process a clean bill of health[23].

Although the 2013 and the 2017 elections were free of violence, there is no evidence that justice was served for the victims of 2007/8 election violence. Furthermore, there was no indication of either a locally made or internationally supported mechanism to facilitate justice. The collapse of ICC cases was in part as a result of local politicisation of the process that resulted in the intimidation of witnesses. In place of justice, the international community and the Kenyan civil society underscored preaching peace. Thus, R2P was not followed up with the a reform process to bring accountability for those who orchestrated violence, but rather on a concerted campaign to avert another calamity premised on the prioritisation of peace at whatever cost. The end result of this has been the rise of authoritarianism and an ever-declining democratic space.

Endnote

[1] Cheeseman, N., Lynch, G., & Willis, J. (2014). Democracy and its discontents: understanding Kenya’s 2013 elections. Journal Of Eastern African Studies, 8(1), 2-24.

[2] Anyang’ Nyong’o, P. 1991. The Implications of Crises and Conflicts in the Upper Nile Valley, in Deng, F.M. & Zartman, I.W. (eds), Conflict Resolution in Africa, 95-114. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution.

Gerhart, G., & Reno, W. (1999). Warlord Politics and African States. Foreign Affairs, 78(2), 158.

Bratton, M., & Van de Walle, N. (2002). Democratic Experiments in Africa: Regime Transitions in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

Mkandawire, T. (2002). The terrible toll of post-colonial ‘rebel movements’ in Africa: towards an explanation of the violence against the peasantry. The Journal Of Modern African Studies, 40(2), 181-215.

Branch, D., & Cheeseman, N. (2006). The politics of control in Kenya: Understanding the bureaucratic-executive state, 1952–78. Review Of African Political Economy, 33(107), 11-31.

[4] Tilly, C. (1992). Coercion, capital and European states, A.D.990-1992 (p. 42). Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell.

[5] Gerhart, G., & Reno, W. (1999). Warlord Politics and African States. Foreign Affairs, 78(2), 158.

[6] Cheeseman, N., Collord, M., & Reyntjens, F. (2018). War and democracy: the legacy of conflict in East Africa. The Journal Of Modern African Studies, 56(01), 31-61.

[7] For more details of politics of “our turn to eat” see Wrong, M. (2010). It’s Our Turn to Eat: The Story of a Kenyan Whistle-Blower. New York: Harper Perennial.

[8] For media report on this story see, https://www.capitalfm.co.ke/news/2013/03/raila-accepts-courts-decision/

[9] For more details of politics of “our turn to eat” see Wrong, M. (2010). It’s Our Turn to Eat: The Story of a Kenyan Whistle-Blower. New York: Harper Perennial.

[10] AfricaFiles | The Waki Commission Report. (2008). Africafiles.org. Retrieved 10 March 2018, from http://www.africafiles.org/article.asp?ID=19264

[11] See Kriegler and Waki reports: summarised version in SearchWorks catalog. Searchworks.stanford.edu. Retrieved 12 March 2018, from https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/9379601

[12] Straziuso, J. (2013). Kenya media self-censoring to reduce vote tension. sandiegouniontribune.com. Retrieved 9 March 2018, from http://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/sdut-kenya-media-self-censoring-to-reduce-vote-tension-2013mar07-story.html

[13] About Ushahidi. (2008). Ushahidi. Retrieved 15 March 2018, from https://www.ushahidi.com/about

Kenya. (2018). Dangerous Speech Project. Retrieved 15 March 2018, from https://dangerousspeech.org/kenya/

[14] National Steering Committee on Peace Building and Conflict Management, “Peace Forums,” available at: http://www.nscpeace.go.ke/peace-stractures/peace-forum.html

[15] Miriam Gathigah, “Kenya: Slum dwellers say ‘no’ to blood money,” Interpress Service, 10 January 2013, available at: https://allafrica.com/stories/201301110766.html

[16] John Harrington Ndeta, “Uwiano; 2012 elections conflict prevention strategy unveiled,” Peacenet Kenya, available at: http://www.peacenetkenya.or.ke/index.php?option=com_content&view=artic le&id=208:uwiano-2012-elections-conflict-prevention-strategyunveiled&catid=3:newsflash#

[17] See ICC names Kenya violence suspects. (2010). BBC News. Retrieved 15 March 2018, from http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-11996652

Africa backs ICC Kenya case delay. (2011). BBC News. Retrieved 15 March 2018, from http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-12332563

[18] See story on https://www.devex.com/news/kenya-clamps-down-on-ngos-after-election-90883

[19] See Michela Wrong, “To be prudent is to be partial,” The New York Times, 14 March 2012, available at: https://latitude.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/03/14/erring-on-the-side-of-caution-kenyas-media-undercovered-the-election/?action=click&contentCollection=Opinion&module=RelatedCoverage®ion=Marginalia&pgtype=article

[20] See Karen Allen, “Kenya’s journalists start to break their election silence,” Mail and Guardian, 22 March 2013, available at: https://mg.co.za/article/2013-03-22-00-kenyas-journalists-start-to-break-their-election-silence/

[21] Agutu, N. (2017). Be a dictator to save Kenya, Jubilee vice chair David Murathe advises Uhuru. The Star, Kenya. Retrieved 7 March 2018, from https://www.the-star.co.ke/news/2017/09/30/be-a-dictator-to-save-kenya-jubilee-vice-chair-david-murathe-advises_c1644625

[22] Atandi, S. (2017). Why Nasa is wary of election observers. Daily Nation. Retrieved 12 March 2018, from https://www.nation.co.ke/oped/opinion/Why-Nasa-is-wary-of-election-observers/440808-4101318-5mkk0jz/index.html

[23] Cheeseman, N. (2017). A look into pivotal role observers play in elections. Daily Nation. Retrieved 11 March 2018, from https://www.nation.co.ke/oped/opinion/A-look-into-pivotal-role-observers-play-in-elections/440808-4202354-t8t7ebz/index.html