- ISSUES IN PEACEBUILDING

10 Years since the Aceh Peace Agreement: Internal Strife Continues

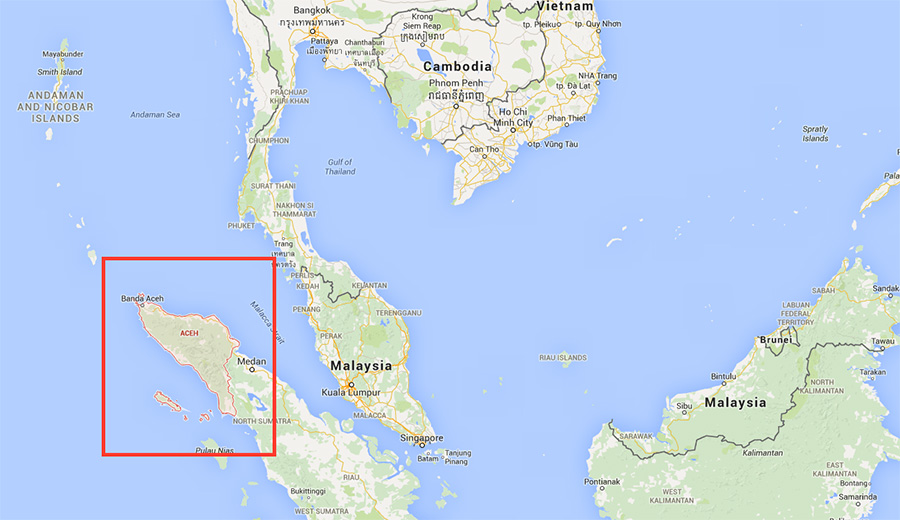

On December 15, 2014, with the tenth anniversary of the Aceh Peace Agreement nearing, the Aceh government opened a peace memorial hall inside the building of the Kesbangpol Linmas, the bureau for citizen protection and political and ethnic unification. This memorial hall stores various documents and materials dating from the Aceh conflict up to the peace agreement. The stated goal was for the hall to become, by the Aceh Peace Agreement’s tenth anniversary on August 15, 2015, a museum for studying the Aceh peace process.

In late 2014, the Konsorsium Aceh Baru (meaning “New Aceh Consortium”), organized by several Acehnese NGOs, set up a peace museum website on the Internet 1 for people to provide materials relating to the Aceh peace process and contribute to peace education. The website’s presentation ceremony was attended by Acehnese as well as people from conflict zones outside Indonesia, such as the Bangsamoro region in Mindanao, southern Philippines, and the Pattani region in southern Thailand.

No Return to Armed Conflict

Although the Aceh peace process still faces a number of problems, these developments make evident that it has proceeded smoothly so far. At least we have not observed any signs that the armed conflict might reignite.

The delegation from Bangsamoro that came to monitor the state of the peace in Aceh also hoped to learn from the experience of the Free Aceh Movement (GAM), which succeeded in making the transition from armed conflict to fighting in a democratic political arena. Bato Mohammad Zainudden, the head of the Bangsamoro delegation, stated the purpose of the trip on December 8, 2014, on this visit to the headquarters of the Aceh Party (Partai Aceh), whose parent organization is the GAM: “The purpose of our visit is to take lessons from the political system and strategies adopted by the Aceh Party as a local political party in Aceh, which, like us, has been granted special autonomy from the central government to formulate its own local rules” (Atjehpost.co/m,08 December 2014).

From Monopolization to Decentralization: Aceh’s Local Parties

In the peace agreement of August 15, 2005, Indonesia’s central government recognized the formation of local parties that are active only in Aceh. This was then written into law in 2006 when the Law on the Governing of Aceh was enacted, and detailed regulations were written on March 16, 2007 when Government Regulation Number 20 of 2007 on Local Political Parties in Aceh was issued.

In response, on June 4, 2007 GAM named Muzakkir Manaf, the movement’s military commander, as the head of their newly formed party, the GAM Party (Partai Gerakan Aceh Merdeka, or Partai GAM for short). However, the government expressed strong reservations against the GAM participating in local politics as a GAM party with the GAM flag as the party banner. Then, on December 10, 2007, Government Regulation Number 77 of 2007 on Local Symbols was issued, banning the use of flags and logos used in separatist movements. GAM, which very much wanted to use the GAM abbreviation in a party name, changed the name to the Aceh Independence Movement Party (Partai Gerakan Aceh Mandiri, or Partai GAM for short) on February 23, 2008 and reapplied, but the government urged them to again reconsider the party name.

Indonesian Peace Institute Interpeace, a body organized by Interpeace, 2 an international peacebuilding organization, mediated between the government and the GAM as tensions arose over the party name. They reached comprise after seven days of meetings that began on April 6, 2008, and on the following April 22 the GAM changed the name to the Aceh Party.

The Aceh Party’s rules list the following four goals of the party.

1) To achieve the vision of the citizens of Aceh in order to decisively maintain their ethnic, religious and national pride and honor.

2) To achieve the vision of the peace agreement between the GAM and the Republic of Indonesia signed in Helsinki, Finland on August 15, 2005.

3) To achieve justice, prosperity and equitable welfare both materialistically and spiritually for all the citizens of Aceh.

4) To respect the truth, justice, the law and humans rights, and to achieve the sovereignty of citizens who develop a democratic lifestyle.

Furthermore, the party’s mission is stated as follows: “To increase transparency for the sake of prosperous lifestyles for the peoples of Indonesia—most of all the citizens of Aceh—and to transform or improve the thinking of Aceh’s citizens so they think of the party as a party of development rather than a party of revolution.” 3

The Aceh Party showed its powerful strength by garnering 46.91 per cent of the votes in the 2009 election for the Aceh Legislative Council, gaining 33 of the 69 seats. This dropped to 35.34 per cent in the 2014 election, but the party still took 29 of 81 seats and maintained its position as the top party in the Legislative Council.

However, the Aceh Party was not the only one to compete in the 2009 and 2014 elections as a local political party. After the peace agreement, 12 parties put their names forward in the 2009 election as local Aceh parties. Of these, the following five parties—including the Aceh Party—actually participated in the election.

Prosperous and Safe Aceh Party (Partai Aceh Seujahtera; PAAS): The party’s basic ideology is Islamic law. Ghazali Abbas Adan of the Development and Unification Party (PPP), a national party, led the formation of the PAAS.

Aceh Sovereignty Party (Partai Daulat Aceh; PDA): The party’s basic ideology is Islamic law. It was formed by Islamic legal scholars (ulama) led by Teungku Harmen Nuriqman, a member of the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR; Indonesia’s national legislature) who is affiliated with the Reform Star Party (PBR).

Independent Voice of the Acehnese Party (Partai Suara Independen Rakyat Aceh; SIRA): The Information Center for a Referendum on Aceh (Sentral Informasi Referendum Aceh; SIRA), which was formed in February 1999 with the purpose of settling the long-running Aceh conflict via a referendum, formed this party in 2007, after the peace agreement. Its leader, Muhammad Nazar, who also led the former organization, took office as Vice Governor of Aceh in 2007.

Aceh People’s Party (Partai Rakyat Aceh; PRA): The Acehnese People’s Democratic Resistance Front (FPDRA), a group of student activists, feminist activists, urban poverty organizations and others, formed this party in 2007.

Aceh Unity Party (Partai Bersatu Atjeh; PBA): This secular party was formed by Ahmad Farhan Hamid, an MPR member affiliated with the National Mandate Party (PAN), which contests elections nationwide.

Apart from the 33 seats in the Aceh Legislative Council that the Aceh Party won in the 2009 election, the Aceh Sovereignty Party was the only one of the other parties listed above, winning only one seat (see Figure 1). Put simply, there was still a very strong idea among the Acehnese that a local political party is synonymous with the Aceh Party, that is GAM.

Figure 1 – Aceh Legislative Council (DPRA) Political Parties by Seats (2009–2014)

| PARTY NAME | SEATS | NOTE |

|---|---|---|

| Aceh Party (Partai Aceh) | 33 | Local party |

| Democratic Party (Partai Demokrat) |

11 | Nat’l party |

| Party of the Functional Groups (Partai Golongan Karya) |

8 | Nat’l party |

| National Mandate Party (Partai Amanat Nasional) |

5 | Nat’l party |

| Development and Unification Party (Partai Persatuan Pembangunan) | 4 | Nat’l party |

| Prosperous Justice Party (Partai Keadilan Sejahtera) |

4 | Nat’l party |

| Patriot Party (Partai Patriot) | 1 | Nat’l party |

| National Awakening Party (Partai Kebangkitan Bangsa) |

1 | Nat’l party |

| Indonesian Justice and Unity Party (Partai Keadilan dan Persatuan Indonesia) | 1 | Nat’l party |

| Aceh Sovereignty Party (Partai Daulat Aceh) |

1 | Nat’l party |

| Crescent Star Party (Partai Bulan Bintang) |

1 | Nat’l party |

| TOTAL | 69 |

Five years later, however, the situation changed somewhat in the 2014 election. The following two parties participated in the 2014 election as local Acehnese parties in addition to the Aceh Party.

Aceh Peace Party (Partai Damai Aceh; PDA): The Aceh Sovereignty Party (PDA), which won one seat in the 2009 Aceh Legislative Council election, changed its name in September 2012. Its leader is Teungku Muhibbussabri A. Wahab.

Aceh National Party (Partai Nasional Aceh; PNA): Irwandi Yusuf, who was the top GAM representative in the Aceh Monitoring Mission (AMM), established in accordance with the peace agreement, and who ran for and won the Aceh gubernatorial election in late 2006, formed this party on December 4, 2011. Irwandi Yusuf is on the party’s consultative council. The party’s chairman is Irwansah, a former GAM commander for Aceh Besar Regency, and its secretary-general is Muharram Idris, who was the Aceh Besar Regency committee chairman for the Aceh Transitional Committee (KPA) that helps armed groups to reintegrate into society. In short, the GAM is split between the Aceh Party and the Aceh National Party.

The Aceh Peace Party gained one seat in the 2014 Aceh Legislative Council election with 3.03 per cent of the vote. The Aceh National Party gained three seats with 4.73 per cent. Meanwhile, the Aceh Party suffered a 10-point loss down to 35.34 per cent from 46.91 per cent in the 2009 election, and gained no more than 29 seats (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 – Aceh Legislative Council (DPRA) Political Parties by Seats (2014–2019)

| PARTY NAME | SEATS | NOTE |

|---|---|---|

| Aceh Party (Partai Aceh) |

29 | Local party |

| Party of the Functional Groups (Partai Golongan Karya) |

9 | Nat’l party |

| Democratic Party (Partai Demokrat) |

8 | Nat’l party |

| National Democratic Party (Partai Nasional Demokrat) |

8 | Nat’l party |

| National Mandate Party (Partai Amanat Nasional) |

7 | Nat’l party |

| Development and Unification Party (Partai Persatuan Pembangunan) | 6 | Nat’l party |

| Prosperous Justice Party (Partai Keadilan Sejahtera) |

4 | Nat’l party |

| Great Indonesia Movement Party (Partai Gerakan Indonesia Raya) | 3 | Nat’l party |

| Aceh National Party (Partai Nasional Aceh) |

3 | Nat’l party |

| National Awakening Party (Partai Kebangkitan Bangsa) |

1 | Nat’l party |

| Aceh Peace Party (Partai Damai Aceh) |

1 | Local party |

| Crescent Star Party (Partai Bulan Bintang) |

1 | Nat’l party |

| Indonesian Justice and Unity Party (Partai Keadilan dan Persatuan Indonesia) | 1 | Nat’l party |

| TOTAL | 81 |

Internal Strife in the GAM: Creeping Political Violence

As the date of the polling on April 9, 2014 approaches in Aceh, where the GAM split is public, there has been a dramatic rise in violence, including murders.

According to an April 7, 2014 report by the Aceh NGO’s Coalition for Human Rights (Koalisi NGO HAM Aceh), there were 61 cases of violence and assault (including shootings) in Aceh against party personnel and supporters in the past year since April 2013. Seven have died, of whom three were members of the Aceh National Party, while the other four were ordinary citizens.

KontraS (the Commission for the Disappeared and Victims of Violence), an Indonesian human rights monitoring organization, compiled the “Report on the Violence and Shootings in Aceh Prior to the 2014 General Election,” which indicated the following five causes behind the sharp increase in violence in Aceh.

First is the feud between the Aceh Party and the Aceh National Party. Even if the fighting between the members and supporters of these two parties was not organized, the parties’ leaders did try to stop the violence. In addition, the facts indisputably show that much of the violence was committed by the Aceh Party members and supporters.

Second, Muzakkir Manaf, leader of the Aceh Party and Vice Governor of Aceh, ridiculed the Aceh National Party (Partai Nasional Aceh; PNA) by coining the pun “Aceh Christian Party” (Partai Nasrani Aceh; PNA) and calling the PNA betrayers to the GAM, thus severely straining the relationship with the Aceh National Party. On March 18, 2014, North Aceh Regency Governor H. Muhammad Thaib said in a speech in support of the Aceh Party that, “nobody will get free rice handouts unless they are Aceh Party supporters.” On March 24, the head of the Lhokseumawe city council, Saifuddin Yunus, publicly said, “We will run those who do not support the Aceh Party out of Aceh.”

Third is the presence of third parties who are using the hostility between the Aceh Party and Aceh National Party to try and intensify the feud. There is a high likelihood that the unattributed acts of violence are sabotage perpetrated by members of the political elite who belong neither to the Aceh Party nor the Aceh National Party.

Fourth is that the police are not firmly clamping down on the prolific violence, and instead are leaving it be. The Acehnese people even suspect that perhaps the police are trying to foment the chaos.

Fifth, the Governor of Aceh has a strong tendency to tolerate violence and is not adequately carrying out his role as a leader. Likewise, the Wali Nanggroe, a traditional leader who rules Aceh according to the Law on the Governing of Aceh, is also not sufficiently contributing to Aceh’s political stability.

The first signs of a GAM split came soon after the peace agreement. In the Aceh gubernatorial election held on December 11, 2006, the GAM leadership and a group of elders backed Human Hamid (a faculty member at Syiah Kuala University) as their candidate for governor, and GAM leader Hasbi Abdullah for vice governor. Meanwhile, the GAM and its young sympathizers backed Irwandi Yusuf, who was the top GAM representative at the AMM, as their candidate for governor, and Muhammad Nazar, the standing chairman of SIRA, for vice governor.

Irwandi Yusuf, who won this electoral battle and became vice governor, ran for reelection in 2012 as an independent cadidate, and again the Aceh Party made various efforts to sabotage his campaign, including trying to convince him to drop out.

The GAM leadership and group of elders—who backed H. Zaini Abdullah (a GAM foreign minister who also worked for many years in Sweden as a doctor) as their candidate for governor, and Muzakkir Manaf (the former GAM military commanders and Aceh Party leader) for vice governor—again was opposed to Irwandi Yusuf in 2012, and they succeeded in taking the governorship and vice governorship. The duo of Zaini Abdullah and Muzakkir Manaf won 55.75 per cent of the votes, while Irwandi Yusuf and Muhyan Yunan (a high-ranking Aceh government official who nominated himself for vice governor) garnered 29.18 per cent of the votes.

Irwandi Yusuf filed for the nullification of the election at the constitutional court for reasons including the 27 acts of violence against his supporters during the campaign, but the case was dismissed. Yusuf was again subjected to violence when he was surrounded outside the Aceh Legislative Council building on June 26, 2012, as he was attending the governor and vice governor’s swearing-in ceremony in the capacity of former governor.

The relationship between Zaini Abdullah and Muzakkir Manaf—who became Aceh’s governor and vice governor, respectively, in 2012—did not remain friendly. The rift between them became public in July 2014 during the election for Indonesia’s president and vice president.

In this election, the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan; PDIP), a national party, and others backed former Governor of Jakarta Joko Widodo as the nominee for president and former Vice President Jusuf Kalla for vice president. Meanwhile, the Great Indonesia Movement Party (Partai Gerakan Indonesia Raya) and others backed former Lieutenant General Prabowo Subianto as their candidate for president and former Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs Hatta Rajasa for vice president. Aceh Governor Zaini Abdullah supported Joko Widodo and Jusuf Kalla, while Muzakkir Manaf supported Prabowo Subianto and Hatta Rajasa.

Vice Governor Muzakkir Manaf, who is also the leader of the Aceh Party, ordered his party’s supporters to give their full support to the Prabowo Subianto and Hatta Rajasa ticket, saying this would assure efforts to wipe out poverty and develop Aceh. Meanwhile, he warned that supporting the opposing camp, the Democratic Party, would be haram, a forbidden act under Islam.

In response, Aceh Governor Zaini Abdullah, who is also a member of the Aceh Party’s consultative council (the Tuha Peuet), criticized such support for Prabowo Subianto and Hatta Rajasa, as this decision was not the party’s but rather an individual choice by Muzakkir Manaf. Abdullah declared his full support for the Joko Widodo and Jusuf Kalla ticket. One reason that Governor Zaini Abdullah supported Joko Widodo and Jusuf Kalla is that former Vice President Jusuf Kalla was the biggest contributor to achieving the 2005 Aceh Peace Agreement and that he could be expected to have the understanding and cooperativeness to solve Aceh’s problems in the future. Other reasons included former Jakarta Governor Joko Widodo’s understanding of Aceh due to his experience working in a state-run enterprise there and his mass appeal due to his clean image.

Aceh Party Leader Muzakkir Manaf, whose order to support Prabowo Subianto and Hatta Rajasa was criticized for not being an official party decision, retorted in writing that the status of the party’s consultative council is no more than honorary and that it has no right to formulate policies. Such developments exemplify the mudslinging that occurred during the election for president and vice president.

Joko Widodo and Jusuf Kalla won the 2014 presidential and vice presidential election in which the Governor and Vice Governor of Aceh supported different camps, although in Aceh they only received 45.61 percent of votes, while Prabowo Subianto and Hatta Rajasa garnered the most (54.39 per cent).

A number of fissures like this one opened within the GAM organization over the 10 years after the peace agreement. In one respect this is fuel for destabilizing public order, but it is probably an inevitable result when one considers that distrust of the Indonesian central government and military has always existed among various Acehnese organizations and individuals under the GAM. The Aceh Party, whose leader is Muzakkir Manaf, a former GAM commander, retains military control even after its formation. One could say that criticism of the party over this and the people who have left the party are proof of the spreading peace in Aceh.

Towards Full Implementation of the Peace Agreement

Although the GAM has shown signs of internal splits as democracy has advanced, none of the factions have changed their stance on respecting and complying with the Law on the Governing of Aceh, which was enacted the year after the 2005 Aceh Peace Agreement.

The problem is that even though the peace agreement is marking its tenth year, a number of its provisions have still not been implemented. Specific examples include the establishment of a human rights court in Aceh, the establishment of a joint committee by the Indonesian government and the Acehnese government to settle unresolved demands, and the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Committee (KKR). On December 27, 2013, the Aceh Legislative Council passed an ordinance (a qanun) concerning the Truth and Reconciliation Committee, giving it the authority to preside over cases of past human rights violations. However, the Ministry of Home Affairs nullified this ordinance because it argued that the Law on the Governing of Aceh only prescribes the Truth and Reconciliation Committee’s establishment, not Aceh’s exclusive authority over it. In other words, the ministry determined that the MPR has the right to pass laws concerning the Truth and Reconciliation Committee, and that Acehnese ordinances must be passed within the scope of those laws.

Likewise, implementation of the rights of the Acehnese government concerning the use of natural resources and land, as prescribed by the Law on the Governing of Aceh, has been slow because the Indonesian government has not defined exact rules. Although Joko Widodo finalized a presidential decree in October 2014, soon after taking office as President, granting the Acehnese government full authority over the National Land Agency (BPN) within Aceh, there have also been strong opinions arguing that granting one region authority over the agency’s functions is tantamount to splitting the state and is unconstitutional.

While the central government is also working to fully implement the Aceh Peace Agreement, we can also say that the fact is that it is working hard to urge caution in Indonesia to maintain consistency with the Constitution and other Indonesian laws.

2. Interpeace (International Peacebuilding Alliance) is an independent, international peacebuilding organization and a strategic partner of the UN, created originally by the UN in 1994 and becoming independent in 2000. ↩️

3. The Aceh Party mission statement can be found here: http://www.partaiacehm2.blogspot.jp/2012/02/profil-partai-aceh html ↩️

Professor, Takushoku University