- BANGLADESH

Six Years of Rohingya Refugee Crisis in Bangladesh: From Here to Where?

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Asia Peacebuilding Initiatives (APBI).

The Rohingya population have been living in the Rakhine state of the predominantly Buddhist nation of Myanmar for centuries. Though they have been living there for generations, the Myanmar government does not recognize the Rohingya ethnic group as a national race. Myanmar introduced a Citizenship Law in 1982 which arbitrarily deprived the Rohingya of their citizenship, labeling them as illegal Bengali immigrants. The 2014 census in Myanmar excluded them from the survey and refused to grant them citizenship.

In reality, they have endured long-standing violence, discrimination, and persecution in Myanmar. For decades, significant numbers of the Rohingya people have migrated across the region due to continued oppression, arbitrary arrests, sexual violence, and severe military actions. A massive exodus of Rohingya took place in August 2017, when the Myanmar military regime launched armed attacks and committed grave human rights violations against them, prompting hundreds of thousands to flee to Bangladesh. The United Nations Human Rights Commission (UNHRC) in September 2017 termed Myanmar’s treatment of its Muslim Rohingya minority as a “textbook example” of ethnic cleansing.

This is not the first time that the Rohingya people have fled to Bangladesh. In 1978, about 200,000 refugees entered Bangladesh, fleeing from persecution by the then military government in Myanmar. In mid-1991, there was another surge of refugees to Bangladesh due to harsh atrocities committed by the Myanmar military. The UNHRC reported that more than 300,000 Rohingya people lived in Bangladesh until 2016.

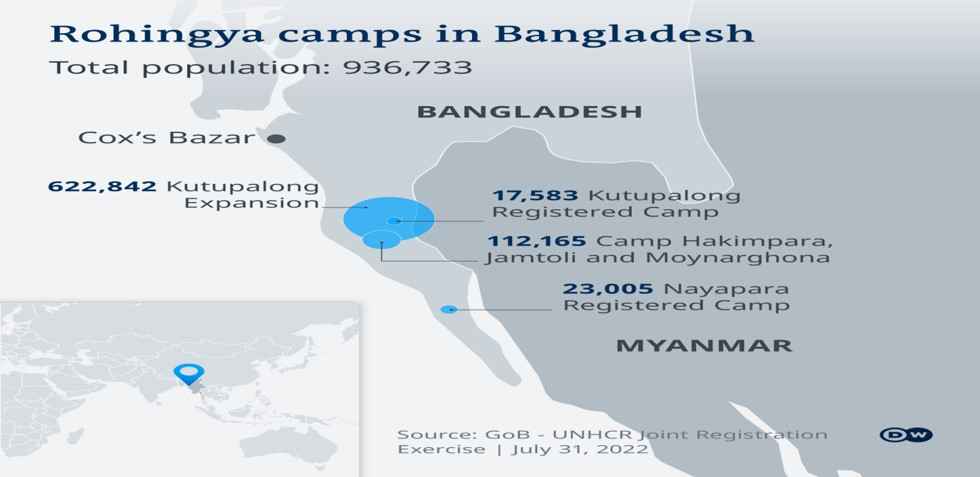

Currently, over 960,000 Rohingya refugees reside in Bangladesh, predominantly in the Cox’s Bazar region, which hosts the world's largest refugee camps. Statistics show that among the refugees, children represent over half (52 percent), with women and girls comprising another 51 percent.

Over the past more than six years, the Rohingya crisis has evolved from a primarily humanitarian issue to a complex challenge with profound political, social, and security dimensions. Six years on, the fading global attention to the Rohingya crisis, together with the February 2021 military coup in Myanmar and the recent (since October 2023) fighting between the military and armed opposition groups, has made the much-awaited repatriation process uncertain and far more complicated.

Situations in Refugee Camps:

As mentioned previously, until now Bangladesh hosts around one million Rohingya populations, who are culturally and linguistically similar to the Chittagonian locals, reside in two primary camps in Cox’s Bazar, including the world's largest, Kutupalong-Balukhali camp. These camps are branded for their high density, significant challenges in sanitation, healthcare, and emergency management. Since the 2017 refugee influx, gradually funding for humanitarian efforts decreased, reaching only 45% of the required amount by late 2023.

This funding shortfall, partly due to global attention shifts, such as, the Ukraine crisis, has led to reduced food aid, inadequate healthcare and education services in the camps. Refugees, especially children, suffer from malnutrition and poor growth, as the World Food Programme had to reduce the food money they provide to each refugee to just $8 a month because of funding crisis. The dire conditions in the camps are prompting many, particularly youth, to risk dangerous journeys to countries like Indonesia and Malaysia causing tragic water grave to many of them. Moreover, the local host community in Cox’s Bazar increasingly resents the prolonged presence of the Rohingya, with a 2019 UNDP survey indicating a growing negative impact on the locals.

In the Rohingya refugee camps, limited access to clean water and sanitation facilities poses serious health risks. Only 30% of refugees have access to safe drinking water, and 85% lack adequate latrine facilities, leading to outbreaks of measles, diarrhea, respiratory, and skin diseases. In 2023, about 40% of refugees were affected by scabies due to overcrowding and insufficient water and medical supplies. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has been treating a range of infectious and chronic diseases since the Rohingya's arrival six years ago. Additionally, the treatment of chronic illnesses like diabetes, hypertension, and hepatitis C has become increasingly necessary, partly due to the lack of longstanding healthcare access in Myanmar.

Moreover, Gender-Based Violence (GBV), as a recent study by Harun and Kusakabe (2024) finds, is a pervasive and deepening concern in the refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar. Since 2017, GBV, particularly domestic violence and sexual harassments together with violence related to marriage against the Rohingya women has increased significantly. Other forms of GBV, as the study reveals, include trafficking, psychological trauma, involvement in criminal activities, issues about the LGBT community etc. “Life within the refugee camps did not alleviate their suffering and, in some cases, exacerbated it.”

The Rohingya refugees’ shelters face significant risks of floods and landslides in their fragile shelters, specially, during Bangladesh's monsoon season, as their shelters are often inadequate to withstand torrential rains and heavy winds. The rainy season also escalates the risk of diseases such as hepatitis, malaria, dengue, and chikungunya, particularly in overcrowded camps with inadequate water and sanitation facilities. Children and the elderly are particularly vulnerable. In May 2023, Cyclone Mocha severely impacted the region, affecting 2.3 million people, including all the 930,000 Rohingya refugees in camps, damaging infrastructure and exacerbating their already precarious living conditions.

Hosting the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh has placed a significant economic burden on its already troubled economy with annual costs exceeding $1.2 billion, far outweighing limited UN aid. The influx has heavily impacted the region's tourism and agriculture sectors, notably causing a 40% drop in hotel reservations during peak seasons. Increased demand for food and other supplies has led to local price hikes disrupting the local job markets for the local population as the Rohingyas accept lower wages. This situation has broadly affected the local economy influencing food prices, wages, and access to essential services like education and health. The environmental consequences of the Rohingya refugee crisis are significant, with approximately 1500 acres of social forest destroyed for shelter and firewood, adversely impacting both the local ecology and communities reliant on these resources. Study shows that total estimated ecosystem services value (ESV) in Cox’s Bazar decreased slightly from $67.83 million in 2017 to $67.78 million in 2021. Additionally, the Rohingyas' illegal attempts to migrate to the South and Middle Eastern countries have created diplomatic challenges for Bangladesh and negatively influenced its international labor reputation and image.

The Bangladesh government remains focused on repatriation as the primary solution to the Rohingya crisis. Political activities within the camps are restricted, although protests demanding repatriation are permitted. To prevent Rohingya integration to the Bengali community, the government prohibits teaching in the Bangla language and restricts the construction of durable shelters. Employment opportunities for refugees are limited, with most only able to work in paid "volunteer" positions for the UN or NGOs. Consequently, many refugees rely on the informal economy for income, with some families operating small shops or businesses in the camps. This situation has led to increased dependence on aid and exacerbated the crisis. However, there have been some positive developments, such as the introduction of Myanmar-language education in the camps which began as a ‘pilot’ project in November 2021 and were fully implemented by 2023, enrolling 300,000 students. Additionally, the U.S. and some other countries have proposed for a third-country resettlement program for vulnerable refugees which shows little progress till date.

To reduce the burden on the existing Camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh government, since December 2020, relocated nearly 30,000 Rohingya refugees to Bhasan Char, a remote silt island located about 60 km away from the mainland under the guidance of the UN agencies. The government has a plan to relocate up to 100,000 Rohingya refugees to the island in phases. According to the Dhaka Tribune, as of January 22, 2023, the number of Rohingyas relocated to Bhasan Char stood at 30,435. From the very beginning, Human Rights organizations criticize Bangladesh’s decision to relocate the Rohingya refugees to Bhasan Char terming it unplanned. Some even call the Bhasan Char Shelter ‘an island jail in the middle of the sea.’ The settlers, however, have mixed reactions about Bhasan Char with some finding lives ‘more or less safe and secured’, and some claiming ‘homesickness’ and urging to make arrangements to go back home in Myanmar.

Repatriation of the Rohingyas: To What Extent?

Bangladesh has been focusing on repatriating the Rohingya refugees to Myanmar's Rakhine State since 1992. After the August 2017 influx, the Bangladesh government again made immediate attempts to repatriate them to Myanmar. To this end, Bangladesh and Myanmar signed an initial deal for the possible repatriation of the Rohingya to Myanmar on November 23, 2017, amid grave concerns raised by the rights groups over the repatriation process. According to the Guardian, the deal was based on a 1992/93 repatriation pact between the two countries in which Bangladesh requested the completion of repatriation within one year and the involvement of the UN organizations’ in the repatriation process. There had always been scepticism, however, about the effectiveness of repatriation process, and till to-date, there is no noticeable progress regarding the repatriation of the Rohingya, mainly because of the noncooperation from the Myanmar side and resistance from armed Rohingya refugee groups.

We can refer to the “Let’s Go Home” campaign by Arakan Rohingya Society for Peace and Human Rights (ARSPH) under the leadership of Mohib Ullah in early 2019 which eventually failed because of the assassination of Mohib Ullah in September 2019. Mohib Ullah’s family accused the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), a group that claims to be working for Rohingya rights, of his murder which the ARSA repeatedly denied. The conflicting groups in the refugee camps including the ARSA often fight for greater social control of the Rohingya refugees camps with frequent and violent clashes between them who also control and regulate the drug trafficking and even human trafficking in the camps. Initially there were campaigns within the camps to put pressure on both Myanmar government and their Bangladesh counterpart to facilitate the repatriation of Rohingya refugees which appeared to be doomed over the time because of increased violence, conflicts and lawlessness. The refugees are in fact divided on repatriation, and they claim that any attempt at repatriation will not address fundamental insecurities if the existing citizenship law of Myanmar is not amended.

The repatriation talks, however, had been on hold due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the military coup in Myanmar in 2021. However, discussions restarted in January 2022, leading to the first joint working group meeting in over three years in June 2022. Bangladesh’s then Foreign Minister AK Abdul Momen in October 2023 emphasized the country's firm stance on repatriation, insisting that Myanmar must guarantee the safety and security of the Rohingya upon their return. He also pointed out that Bangladesh, with its already large population, cannot accommodate a significant number of people from other countries. Bangladesh has repeatedly emphasis on ‘repatriation, not integration’ as a sustainable solution to the Rohingya crisis. Despite ongoing discussions, the process of repatriation has progressed slowly.

In an attempt to initiate the repatriation of Rohingya refugees, the Bangladesh government has proposed a "pilot" or trial run, leaving the resolution of rights issues to Myanmar's military regime. In early 2023, Bangladesh and Myanmar agreed to a pilot project to repatriate 1,176 Rohingya refugees to Rakhine State. The project, however, faced challenges as the repatriation did not guarantee return to their original villages. Despite efforts to show favorable conditions, including tours in Rakhine, the refugees hesitated to return without clear assurances on citizenship and the ability to return to their ancestral homes. Myanmar's ambiguous response, offering settlement in new or existing villages, did not fully meet the refugees' demands. Consequently, the UN refugee agency and rights groups have opposed the trial repatriation due to the lack of a suitable and safe environment there. UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, Tom Andrews suggested that “Conditions in Myanmar are anything but conducive for the safe, dignified, sustainable, and voluntary return of Rohingya refugees…The return of Rohingya refugees under these conditions would likely violate Bangladesh’s obligations under international law and expose Rohingya to gross human rights violations and, potentially, future atrocity crimes” (June 8, 2023). Experts opine that repatriation process must consider the prospects for their integration to the system, access to fundamental rights and more importantly the restoration of their dignity in the Myanmar state. Earlier, the UN and World Bank suggested Bangladesh to allow the Rohingya people the freedom of movement, and other privileges, including education and job, like those enjoyed by the Bangladeshis which characterizes a shift from the earlier advocacy for repatriation of the global community, and sparkled a debate on whether the global community's approach prioritizes convenience over the Rohingyas' desire to return home under appropriate conditions. Bangladesh, however, reasonably denied any process of integration of the Rohingya into Bangladeshi society, and urged the world leaders, and the UN to ensure their quick repatriation to Myanmar.

Rohingya Refugee Repatriation: Victim of Global and Regional Politics?

The Rohingya refugee crisis drew wider global attention at the very beginning in late 2017 having significant international sympathy and financial support. The US has significantly contributed to support the Rohingya providing over $1.9 billion in humanitarian aid for those in Bangladesh and affected regions, including Myanmar. This aid aims not just to address basic needs but also to improve resilience, economic security, and dignity through educational and livelihood initiatives. However, by 2020, humanitarian aid funds dropped to 65% of the required amount and further declined to 34% in 2021, with only $366 million of the necessary funds provided. As of mid-August 2023, the humanitarian agencies have received just 28.9% of the required $876 million to support refugees and local communities in Bangladesh. This lack of funds, as mentioned previously, has led to reduced food assistance and intensified concerns over malnutrition, child labor, and gender-based violence (GBV) in the camps. The UNHCR has been urging for more international support, focusing on education and skills development of the refugees and advocating for their sustainable repatriation to Myanmar.

Today, at the seventh year of the Rohingya crisis in, the media attention span has apparently moved on to other stories. Similarly, international repatriation efforts have been markedly inadequate. Consequently, this question has been very pertinent: have the Rohingya refugees been victims of global silence? While part of the solution to the Rohingya crisis lies in a political goodwill of Myanmar, the international community also has an indispensable role to play. Bangladesh has incredibly allowed the Rohingya refugees in, despite firm shortcomings of its own. It is now an obligation for other countries in the region and beyond to take more responsibility, and support Bangladesh through humanitarian aids and make consolidated diplomatic efforts to prompt repatriation process. Bangladesh has repeatedly appealed to countries like the United States, China, India, Japan, South Korea and the ASEAN to make pressure on Myanmar for a safe return of the Rohingya refugees to their homeland with insignificant responses from them.

However, as a matter of great regret, part of powerful actors like China, India, Russia, part of ASEAN, and some other countries are ostensibly reluctant to act in the Rohingya crisis citing the issue related to Myanmar’s sovereignty, and the principle of non-interference. Until now, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) failed to implement any effective measure to address the Rohingya issue due to opposition from China and Russia.

China’s long association with Myanmar, both economically and diplomatically, was evident in the 2017 UNSC meeting on Myanmar where China blocked a resolution to condemn Myanmar for its atrocities against the Rohingya ethnic minority. China is building a deep seaport in Kyaukpyu, Rakhine state to enhance connectivity, and has already invested billions of dollars to establish oil and gas pipelines from the port to the landlocked Chinese province of Yunnan under its Belt and Road initiative. Apparently, the Rohingya crisis has given China an additional opportunity to cement bilateral ties with Myanmar. China considers Myanmar a key gateway to the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean. China, being Myanmar’s largest trading partner, with major infrastructure projects underway, wants to make sure that its economic interests are secured. All these factors so far restricted China from taking any decision that goes against Myanmar’s interest. Nonetheless, the role of China is thought to be very instrumental to further the repatriation process.

On the other hand, India, who also hosts a large number of Rohingya refugees in its territory, has largely been inactive in the process of the repatriation of the Rohingya refugees so far. Reasonably, India wants to maintain an effective bilateral relation with Myanmar to defend its geopolitical and geo-economic interests, notably to control ethnic insurgencies in North-Eastern India, curb cross-border smuggling of arms and drugs, gain access to Myanmar’s huge hydrocarbon deposits, and establish physical connectivity to wider Southeast Asia through Myanmar. This might have made India, despite its bilateral warmth with the current regime of Bangladesh, support Myanmar at the United Nations (UN) on the Rohingya issue. One analyst, however, argues that ‘India should assist Bangladesh in the repatriation of the refugees to Myanmar to facilitate further Indo-Bangladesh engagement in the security sector and ensure Bangladesh’s continued “benevolent neutrality” in the Sino-Indian rivalry.’

From the very beginning, Bangladesh has been very active in multilateral forums to seek their support for Rohingya repatriation. More prominently, regional organizations such as ASEAN and SAARC were expected to take a leadership role in resolving the Rohingya crisis. But, ironically, ASEAN finds itself caught between its core principles of consensus and non-interference, which has hindered its ability to respond effectively to the crisis, with SAARC has apparently proved itself a dysfunctional organization in South Asia. On April 24, 2021, ASEAN leaders agreed on a 5-point consensus to end violence in Myanmar though progress so far has been very minimal. Indonesia’s efforts to negotiate have not yielded visible results, while Malaysia who is currently hosting roughly 100,000 Rohingyas is outspoken concerning the issue. On the other hand, Thailand, with a long border with Myanmar and hosting many refugees, has tightened border controls. Similarly, Singapore, more concerned about humanitarian aid, seems hesitant to act against Myanmar due to investment interests.

Japans’ Position:

Unlike the Western liberal democracies, Japan had initially been muted in voicing criticism against the atrocities committed by Myanmar against the Rohingya people, thus, following the footsteps of many other Asian countries. Japan also abstained from voting on the resolutions condemning the Myanmar government at the Third Committee of the United Nations General Assembly on November 16, 2017, and the UN Human Rights Committee on December 5, 2017 respectively, drawing frustrations from Bangladesh and beyond. However, then Japanese Foreign Minister Taro Kono’s visit to the refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar in November 2017 drew wider appreciation from Bangladesh and beyond. In 2019, during his visit to Dhaka, Kono expressed his country’s readiness to actively perform a role of mediator between Bangladesh and Myanmar to ensure immediate and smooth repatriation of the Rohingya refugees to their place of origin in Myanmar which did not come into reality until now. At both the visits, Kono made promises for financial supports to address the crisis. Since August 2017, Japan has contributed over $200 million to support the Rohingya through the UNHCR, other UN agencies, and NGOs. In 2023, Japan and the UNHCR agreed to provide $2.9 million for ongoing assistance and protection for refugees in Cox’s Bazar and Bhasan Char. Japan's significant aid includes a recent $4.4 million for food through the WFP, adding to earlier aid in March 2023. Additionally, the Japanese government has given $5.7 million to the IOM to improve living conditions for the Rohingya in Cox's Bazar and Bhasan Char. Japan's contributions have been crucial in providing shelter, healthcare, and services to the Rohingya and host communities.

During Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s visit to Japan in April, 2023, both Japan and Bangladesh agreed that “protracted displacement will lead to increased burden on the host communities and instability in the region and that an ultimate solution to this crisis for peace and stability across the region is to realize a sustainable, safe, voluntary, and dignified repatriation of the displaced persons to Myanmar.” Prime Minister Hasina also appreciated “Japan’s support for the displaced persons thus far, including its humanitarian assistance as the first country to do so for those resettled in Bhasan Char.” Still, Japan is expected to use its full weights to pressure the military government in Myanmar in place of deploying its preferred ‘passive diplomacy.’ Japan’s apparent reluctance to criticize Myanmar on the human rights abuses against the Rohingya can be linked to Japan’s economic interest in Myanmar, and its competition with China in the country. Human Rights Watch criticizes Japan for its growing financial engagement with Myanmar. It is important to mention here that Japan never uses the term ‘Rohingya’ in its official documents, rather they use the term ‘forcibly displaced persons’ which, probably, is comfortable to the military regime of Myanmar. The Japanese government, however, criticized the February 1, 2021 military coup in Myanmar, arrest of Aung San Suu Kyi, and urged the Junta to ‘swiftly restore the democratic political system of the country.’

Looking Ahead:

At the time of the writing of this report, the Myanmar troops and the Arakan Army have been locked in a fierce battle in Rakhine, taking control of most of the border posts, and causing hundreds of the junta forces fleeing to Bangladesh territory for the first time in history. This may intensify the crisis in Rakhine sparking the possibilities of further fresh influx of Rohingyas in Bangladesh to flee attacks. Nikkei Asia (February 21, 2024) reports that hundreds of Rohingyas had gathered at various points along with the borders seeking shelter in Bangladesh. Bangladesh, however, firmly denies allowing no more Rohingya refugees entering the country. US Assistant Secretary for South and Central Asia, Donald Lu, recently voiced concerns over risks to Bangladesh and India stemming from the Rohingya crisis and the ongoing conflicts between the junta military and different rebel groups in Myanmar, notably the Arakan Army. He warns that the refugee crisis together with security concerns could get deeper in the coming days.

The National Unity Government (NUG), a shadow government in exile, has apparently changed its attitudes towards the Rohingya population since the coup in February 2021. The NUG issued a statement regarding its Rohingya policy in June 2021 and reiterated its position in March 2022 committing for “the safe, voluntary, dignified, and sustainable return of Rohingya refugees and internally displaced persons, and to comprehensive legislative and policy reform in support of citizenship, equality in rights and opportunity, and justice and reparations." The NUG also appointed Aung Kyaw Moe, a Rohingya, as its human rights adviser. Recently, Kyaw Zaw, adviser to the President of the NUG, on January 31, 2024 virtually joined a symposium in Dhaka and noted that ‘once ongoing people’s revolution would overcome the brutal military regime; the NUG would work unitedly with ethnic organizations, notably with the Rohingya representatives, to invigorate the repatriation process’ even though many of its members rejected the repatriation process before 2021. Similar view was expressed by Dr. Win Myat Aye, Minister in charge of Humanitarian Affairs and Disaster Management of the NUG government on January 20, 2024 in Tokyo during his personal conversation with this author. However, as the NUG has hardly any real political power in Myanmar, its statement currently amounts to little more than a declaration of intent.

As mentioned previously, Bangladesh, with its high population density and limited resources, faces daunting challenges in supporting the vast number of refugees. The COVID-19 pandemic intensified the struggle to uphold health and safety standards in the densely packed refugee camps. Even after the pandemic, the situation remains critical, as the UN has reduced food aid for the Rohingya, leading to a significant decrease in their food supply. Moreover, the security situation in the Rohingya camps had worsened because of armed and criminal activities including increased violence, abductions, and their involvement in drug trade. The effectiveness of Bangladeshi security forces, mainly the Armed Police Battalion, in managing these issues has been hindered by allegations of corruption and collusion with these groups.

Although Bangladesh has been a ‘shelter’ for the Rohingya refugees for over the past forty years, it has never accepted them as refugees, rather labeled them as Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals (FDMNs). It is a matter of great concern that for the last four decades, there has been little progress in repatriating them to Myanmar. To effectively address this issue, a joint effort from global actors including international and regional organizations is necessary to formulate a workable plan tackling the underlying problems. The UN and other international organizations must put on stronger pressure on Myanmar to begin the repatriation process immediately. Therefore, a pragmatic approach to repatriation is needed including continuous dialogue with Naypyidaw, and, if necessary, to engage with the Arakan Army who are presently fighting the military regime of Myanmar for greater autonomy of Rakhine. We sincerely hope that the Rohingya people will not be the “Next Bihari Refugees” in Bangladesh as apprehended by Masaaki Ohashi (2024).

PhD, Professor of Political Science, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh