Article

*Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited

February 22, 2023

“Linkage of Fighting and Thinking” as Seen in the U.S. Army’s

Unified Pacific Wargame Series

Hiroyasu Akutsu

(Research Fellow, Sasakawa Peace Foundation/Professor, Faculty of Law, Heisei International University)

Foreword

This author previously discussed the current state of wargaming in the U.S. Pacific Deterrence Initiative in another article.[1] A number of wargames have been conducted since the beginning of 2022. This article will explain the wargames developed and conducted at the U.S. Army’s Center for Army Analysis (CAA). However, since the concrete scenarios in the wargames have not been made public at this point, this article will only deal with the format of the wargames within the limit of the available information and give an overview of the programs where these wargames were a part.[2] It will also touch on the facilitated discussions, which were included as a set with the wargames in these programs, and the significance of such discussions.

U.S. Army Unified Pacific Wargame Series

This article discusses the U.S. Army’s “Unified Pacific Wargame Series” consisting of various wargame programs employing the CAA Accelerated Wargaming System(CAAAWS).[3] This wargame series was hosted by Gen. Charles Flynn, U.S. Army Pacific Commanding General, and the wargame programs were sponsored by Gen. James C. McConville, U.S. Army Chief of Staff.

The first part mainly consisted of a seminar-style facilitated discussion (FD) on “Maneuver in Competition.” This FD was held at the Schofield Barracks on Jan. 10–14, 2022, with 76 active duty officers participating. The main purpose was to consider 43 specific operations, activities, and resourcing proposals suggested by the U.S. Pacific Army within the timeframe from the present to 2030. A more wide-ranging and detailed discussion took place on an assessment of their feasibility, sustainability, and acceptability from the standpoint of each U.S. Army site, theater, and region. Finally, deliberation of more detailed topics taking resourcing into account was conducted, through which discussions to identify various risks and opportunities were held.

In part two, the wargame “Fight Beyond the First Battle” was conducted at the U.S. Army base Schofield Barracks on Oahu Island, Hawaii from April 4–8, 2022. Lessons learned after the wargame have not been made public, but there have been reports on part of the outlines of the programs. This wargame was computer-aided and replicable. It was a free-play joint operations wargame based on a highly transparent referee system pitting the blue force against the red force. More than 200 officials from the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), various U.S. Army units, the Indo-Pacific Command and its subordinate organizations, and other offices reportedly participated in this exercise.[4]

In the wargame, the blue force, or the joint force players, was assigned the task of considering two different courses of action.[5] The players were reportedly asked to identify the risks and opportunities of these courses of action and make a final decision from the standpoint of a commanding officer on the battlefield. It goes without saying that the scope of these courses of action covered all areas, from the army, navy, and air force to the space, cyber, and electromagnetic realms, or the so-called new domains in Japan.

The third and last part was the “Fight in Conflict” program combining the CAAAWS and FD held at the Schofield Barracks on May 9–13, 2022 with over 200 participants.[6] Details of the wargame, including the scenario, are confidential but apparently, it was an exercise on how to continue fighting the enemy for several months under a situation of supply shortage at the theater level. Here, the players’ actions were judged by the CAAAWS, and they were required to do a comparative study of the two courses of action. Furthermore, 45 participating generals considered tactical and strategic risks from three different points of view: joint and combined interoperability, strengthening and maintaining operational endurance, and integrated deterrence through joint operations.

In addition, during the last week of these three programs, a “board game” focused on fighting and a “strategic discussion” focusing on lessons learned from the fighting were held.

The above is all the information disclosed by the U.S. Forces. Details of specific scenarios and lessons learned remain confidential. However, the fact that a total of nearly 500 elite generals and other participants from outside the U.S. Forces and Department of Defense, including the State Department, were involved in the programs consisting of wargames and group discussions held over six months points to the U.S.’s strong military commitment to the Indo-Pacific.

Facilitated Discussion

In wargaming, normally the team members will discuss among themselves or with other teams to review the course of the wargame after it is over (such sessions are often called After Action Review: AAR).

The person who assists such discussions or serves as moderator is commonly known as a facilitator[7]. This facilitator is a specialist whose purpose is to promote smooth discussion within a group. He/she does not join the discussion but provides support to the participants from the sideline to ensure a lively discussion. Specialist facilitators who provide support for the team discussions and moderates the AAR are also present at the military’s wargaming. Discussions led by facilitators are called facilitated discussion (FD)[8]. The programs of the Unified Pacific Wargame Series were made up of three parts consisting of a combination of wargames and FDs.

Of the three programs above, parts two and three clearly involved the combination of wargames and FDs. Normally, brief exchange of views to review the wargame takes place after its completion. This is common knowledge to anyone who has participated in a wargame.

However, what is important here is not the program format of combining wargame and FD, but the quality of the wargame plus the capability of the facilitator leading the FD. The U.S. Forces train facilitators specializing in wargames through its education programs. In special cases, veteran facilitators are sent to the U.S. Forces and the armed forces of the allies. In other words, facilitators go beyond the level of simple moderators or organizers of discussions. They are required to be very high-level experts who possess general and more specialized capabilities. This is a point the Japanese government and the Self Defense Forces need to take note of when training wargaming experts because capable facilitators are essential for appropriate red teaming and drawing more general takeaways and lessons from specific wargames.

Comments on the Unified Pacific Wargame Series

Lastly, I would like to cite the comments voiced by U.S. Army commanders and other officials on the Unified Pacific Wargame Series. U.S. Army Pacific Commanding General Flynn, the overall host of this program, stated: “This is going to be invaluable for the Joint Force. Wargaming is a way to test your plans. It's a way to look at new concepts. It's a way to identify capability gaps. From the concepts and the capabilities and the gaps that you identify, you can come up with ideas and paths to creating warfighting advantages.”

Lt. Col. Tim Doyle, Unified Pacific Wargame Series lead planner, said: “The aim [of this wargame series] was to provide an experiential learning environment for senior leaders to identify and better understand strategic and operational problems.”[9]

On the other hand, Lt. Gen. Xavier Brunson, Commanding General of the U.S. Army’s First Corps who also participated in the wargame, observed: “The theater commander counts on us to be the operational warfighting headquarters in the Indo-Pacific. It's very important to understand the lessons learned and the way those headquarters above are going to fight and win in prevailing conflict… For us, the value is in understanding a little bit more about joint and multi-domain condition settings. It’s about thinking about our posture differently. It's about how we go about helping the Theater Army achieve a positional advantage in the Indo-Pacific.”[10]

Lastly, Flynn cited the two parallel efforts consisting of wargaming and FD as the unique feature of this wargame series. Flynn gave the following comments:

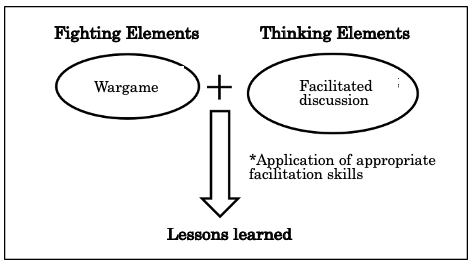

One effort [in this program] was the actual wargaming itself, where there were units, formations, and capabilities in all the domains conducting operations. They were basically doing the action, reaction, counteraction, and then having a series of outcomes. That standard typical wargaming effort was going on in one track. The second track in parallel with that was we had these senior leader seminars and academics to talk about things like interoperability, joint and combined interoperability, to talk about operational endurance and the challenges with operational endurance, and to talk about things like integrated deterrence and joint campaigning. I think the idea of having those two parallel tracks where there was a fighting element of the wargame, and a thinking element of the war game was really invaluable. It was very innovative and a creative way to set the war game up. I think the combination of the insights from both the thinking part of it and the fighting part of it is going to be really rich in the final analysis.”[11]

I would like to add that the role of facilitators specializing in wargaming is important for deriving the insights and lessons mentioned above. (See Diagram 1)

Diagram 1 Linkage of Fighting and Thinking Elements in Wargaming

(Source: Created by the author)

Furthermore, the specialized skills of facilitators are regarded as a given by the U.S. and British forces, so the reports and other documents on the Unified Pacific Wargame Series would not take any particular note of them.

Conclusion

This article gives an overview of the U.S. Army’s Unified Pacific Wargame Series that started in January 2022. I would like to stress in particular that this program was not only a wargame simulating the U.S. Forces’ fighting; it also provided considerable thinking opportunities through FDs, where facilitators gave support from the sideline in the discussions. As Gen. Flynn pointed out, the optimum combination of the fighting elements in the wargame and the thinking elements in the FD enables meaningful learning and lessons. In Japan, when similar programs are planned, they must not end with just a one-time wargame or a “critique” by a lecturer after the event. The AAR or the so-called “hotwash” discussion held immediately after the event to assess and deliberate on the wargame must not simply be a meeting for voicing superficial impressions. They need to be an occasion for participants to seriously review their own play in a systematic manner. The FD part also needs to be taken into full consideration at the planning stage in order to ensure that the data and insights obtained at the wargames can be collated as lessons learned subsequently.

In this article, the author emphasizes the importance of facilitators based on his personal experience. Japan also needs to consider improving facilitation skills and developing human resources in order to enhance the quality of FD. Particularly in wargaming, it is important for Japan to make steady efforts to build the foundation for what is taken for granted in the UK and the U.S.

The U.S. Army’s First Corps also participated in this Unified Pacific Wargame Series. This means that, in light of the current Pacific Deterrence Initiative, it is fairly conceivable that the scenarios used in the wargames are closely related to Japan’s security. While the publicly available reports have not mentioned any participants from Japan, if there were Japanese participants, it is hoped that the results of their participation will be utilized for the development of wargaming by Japan’s Self Defense Forces. Incidentally, the U.S. Military Operations Research Society (MORS) is holding its “Wargaming with Pacific Partners Special Meeting” in Hawaii from Feb. 27 to March 1, 2023, and they are soliciting participants from Japan.[12] It is hoped that there will be many participants from Japan in this meeting.

1 Hiroyasu Akutsu, “New Development in Wargaming as Seen in the U.S. Pacific Deterrence Initiative: A Decision-Making Tool Japan Should Actively Employ” (Oct.11, 2022).

2 Steven A. Stoddard, “Wargaming the Army’s Role in the Indo-Pacific,” Phalanx, Military Operations Research Society (MORS), Fall 2022, pp. 40-42; and Craig Childs, “Unified Pacific Offers Critical Insights into The Theater Army’s Contribution to Joint Warfighting Concepts in the Indo-Pacific,” United States Army News, May 19, 2022.

3 CAA Accelerated Wargaming System(CAAAWS) in English.

4 Childs, op. cit.

5 In this case, “course of action (COA)” in English.

6 Part of the program was conducted at Fort Shaffer, where U.S. State Department officials reportedly participated.

7 “Facilitation techniques” are known in capacity development and other fields in Japan today. However, the facilitation training this author joined in the U.S. was aimed at acquiring general skills applicable to many areas, and trainees are given “effective facilitator” certification after completing the course. The training consisted of basic management skills relating to encouraging participation in discussions, preventing confusion and distraction in the discussion, and calling attention to wrap up the discussion within the allotted time, as well as how to act as traffic cop for the discussion and guide this toward consensus building. There are also training programs for acquiring facilitation skills in specific areas, such as strategic planning, scenario planning, negotiation, and conflict resolution. The military’s educational institutions have training programs for facilitators specializing in wargaming. On this subject, see e.g., Jeff Appleget, Robert Burks, Fred Cameron, The Craft of Wargaming: A Detailed Planning Guide for Defense Planners and Analysts (Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2020).

8 FD is sometimes called tabletop exercise (TTX) since it is conducted on the table or desk.

9 Childs, op. cit.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.