- Top

- Publications

- Ocean Newsletter

- The Raising of the 'Ehime-Maru' and the Current State of Salvage Operations from the Deep-Sea

Ocean Newsletter

No.20 June 5, 2001

-

The 'Ehime-Maru' Incident from a Different Perspective

Masanobu TERADA

Secretary, Marine Traffic System Forum

Selected Papers No.2The "Ehime-Maru" accident was a tragic incident, in which a mistake by the US Navy took the lives of nine people, including several young high school students. For a period after the incident, the Japanese media, in conjunction with many websites, gathered much sympathy for the lost crew and reported extensively on the emotional aspects of the tragedy. However, there were few references made to the different values of Japanese and American people in terms of the political system in America that caused the collision, the rescue effort after the accident and the raising of the sunken "Ehime-Maru".

Selected Papers No.2 -

The Raising of the 'Ehime-Maru' and the Current State of Salvage Operations from the Deep-Sea

Nobuo SHIMIZU

Manager, Deep Sea Development Group, Fukada Salvage & Marine Works Co. Ltd.

Selected Papers No.2The present situation in deep-sea salvage operations, which involve extraordinary costs, is that no commercial market yet exists. This raises many questions concerning both the equipment and technological aspects of such heavy-duty deep-sea activities. Consequently, in raising the Ehime-Maru 610m from the sea floor, many difficulties can be anticipated. At the same time, however, hopefully it will also trigger many significant breakthroughs in the development of deep-sea salvage technology.

Selected Papers No.2 -

Playing with the Critters in Mudflats

Shinobu WATASUE

Chief, Encounter Network "Friends"Many crabs and precious shellfish inhabit the vast mudflats of Moriye Bay in Kitsuki City (Oita Prefecture), and this provides the perfect environment for children to become familiar with nature. However, it is with extreme regret that we can only stand and watch as the critters in the mudflats continue to be decreased by the maintenance operations of the nearby fishing port.

The Raising of the 'Ehime-Maru' and the Current State of Salvage Operations from the Deep-Sea

The present situation in deep-sea salvage operations, which involve extraordinary costs, is that no commercial market yet exists. This raises many questions concerning both the equipment and technological aspects of such heavy-duty deep-sea activities. Consequently, in raising the Ehime-Maru 610m from the sea floor, many difficulties can be anticipated. At the same time, however, hopefully it will also trigger many significant breakthroughs in the development of deep-sea salvage technology.

Background to the Decision to Salvage the Ehime-Maru

At about 1:45pm on the 10th of February 2001, the "USS Greenville", a US Navy nuclear powered submarine, plowed into the Ehime-Maru, a 499-long ton marine training vessel, owned by the Ehime Marine High School of Uwajima City in Ehime. The "Greenville" was in the middle of a rapid resurfacing maneuver, 10.2 miles (18.5 kms) off the coast of Diamond Head in Oahu Island, Hawaii. The vessel sank without even a moment's notice and now sits on the sea floor, 610 meters from the surface. Almost immediately after the impact, the crew of the Ehime-Maru attempted their own rescue operation, but tragically the accident ended in the lives of nine people being lost. Forty-five minutes after the collision, the US Coast Guard's rescue ship arrived on the scene to pick up the survivors and search for the missing crewmembers. In the following days, the search was continued by air and sea, right around the clock. The US Navy also requested the use of other apparatus such as "Remotely Operated Vehicles" (ROVs) and "Side Scan Sonars", enabling a stereoscopic search to be made of the area from air to sea floor. Alas, no sign of the nine victims was ever found, and after almost a month of activities, the search was called off.

Judging by the way the Ehime-Maru disappeared below the surface less than fifteen minutes after the impact, it became obvious to the grieving parties that the missing nine people were more than likely trapped below deck, leading to increasing pleas for the sunken vessel to be recovered, in addition to the cries to extend the search and rescue effort. In reply to Japan's requests, the United States government indicated they would do everything in their power to recover the bodies of the missing, and consequently operations began moving towards the raising of the sunken vessel. A two-month environmental assessment of the area was completed as the first stage of the operations, and following this, it was estimated that a start could be made on the recovery this coming summer.

Under the US Navy framework, all salvage operations of US Navy or related aircraft and ships are consigned by contract to private enterprises. The Ehime-Maru salvage was accordingly consigned to the Dutch salvaging company "Smit International" who were signed up with US Navy at the time. I was also involved in the early salvaging developments. I served as a salvage advisor from February 12th-27th following the collision, at the "Ehime-Maru Rescue Response Center", which was set up by the Japanese Consulate in Hawaii, and also investigated the possibility of making a salvage through the observation of the under water operations of the ROVs "Scorpio" and "Deep Drone"

The Current State of Deep-Sea Salvaging Operations

Japan's record in deep-sea salvaging is the raising of a 50-long ton private marine research vessel "Heriosu" from a depth of 240 meters, after it sank off the coast of Iwashiro in Fukushima Prefecture in July 1988. Successful salvage operations on large vessels of up to 6,000-long tons have been made in shallower waters too, similar to most other smaller recovery attempts that are ordered by insurance companies for vessels sunk in waters that are no deeper than 50 meters. However, salvages are only made when the insurance policy held on the ship (Main Body Insurance) is more than the quote made by the salvage company. In the case that the insurance doesn't cover the salvage costs, the entire insurance payout goes to the ship owner and no salvage attempt is made. The rough cut off point for an economic salvage is therefore around 50 meters, the same depth that is about the limit for general scuba divers. For this reason, there is no commercial market for salvage operations on vessels lying at great depths.

However, due to recent developments in environmental and humanitarian issues, there is a growing need for a deep-sea salvage industry. The "Heriosu" salvage mentioned above and the recovery of the Ehime-Maru are just two examples of this. The salvage of the Russian tanker "Nakhodka" that caused one of the worlds worst oil spills (the main hull of the ship has been identified at a depth of 2,500 meters) and the child evacuation ship "Tsushima-Maru" (which has been identified at a depth of 840m) have also been discussed by the Japanese government.

Additionally, the nuclear powered Russian submarine "Kursk" that sank last year to a depth of 105 meters, with an underwater weight 18,000 tons (scheduled to be raised during summer this year) and the Russian Komsomolets that sank in April 1989 and has been traced to a depth of 1,682 meters, with a underwater weight of 4,500 tons, are further examples of potential targets for deep-sea operations internationally. This is not forgetting the more recent gas explosion on oil production plant "P36" off the coast of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, which resulted in the structure sinking nearly 2000 meters to the sea floor.

In regards to the mere surveying of structures to be uplifted from the sea floor, with the exception of interior surveys, in this day and age there aren't many depths where technology can't go. Furthermore, even in deep-sea regions, the recovery of several ton pieces of crashed aircraft, rockets and other debris is also a very feasible extension of surveying activities.

The Ehime-Maru salvage, however, is a heavy-duty operation that has to be undertaken in a deep subterranean environment, and that will require a culmination of all the available technology.

The Technological Aspects of the Ehime-Maru Salvage

As I have stated in the above text, the deep-sea isn't targeted by commercial salvage operations, and so the fact is when it comes to taking on such an operation, mainly due to a lack of specialized machinery and equipment, a quick response is virtually impossible. Especially for underwater equipment, emergency manufacturing often isn't possible and there is a limit to what can be done with the operational technology available commercially.

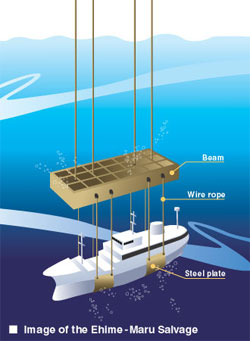

In terms of specific issues related to the raising of the Ehime-Maru, one of the biggest issues is the method of attaching the necessary cables to the hull of the ship. The limit for commercial divers who make such operations is about 300 meters, so for anything deeper operations are reliant upon unmanned ROVs. In the case whereby a sunken ship lies on flat on the sea floor, it is normal procedure to lift the stern of the ship and then pass cables under the hull through the space created between the ship and the sea floor. However, for the Ehime-Maru a robot must be used, so it is a case of how much can be dug out from under the hull of the ship, so that cables or metal plates can be passed underneath. Furthermore, I have heard that the lifting cables are to be attached to a lifting beam (diagram above). Therefore, another big issue will be how this attachment is going to be made. The thickness of the lifting cables necessary will be in the vicinity of 110mm, and they will probably weigh more than 50 kilograms per meter, so it will be interesting to see how a ROV will be able to handle such heavy material.

These kinds of issues will no doubt be the biggest points of attention in the Ehime-Maru salvage later this summer. However, not only will the operation be of great reference to deep-sea salvage activities of the future, but it is also likely to set the global standard for deep-sea salvage technology.

As I mentioned earlier in this text, the heavy-duty operations that are required as a consequence of accidents in the deep-seas involve many technological and equipment-manufacturing issues, and there are many cases of emergency responses not being able to be made at the commercial level. For this purpose and from a different point of view, I also hope the Ehime-Maru tragedy will provide the turning point for developing deep-sea accident prevention measures.

Finally, I would like to express my deepest sympathy to the family and friends of the missing 5 crewmembers and the 4 students. I hope that they will be reunited with the remains of their loved ones in the very near future and that they recover from their tragic loss as soon as possible.