- THAILAND'S DEEP SOUTH

Reflections on the Peace Dialogue in Southern Thailand Between the NSC and BRN

Unhappiness and frustration might best sum up the working relations between past Thai governments and their Malaysian counterparts when it comes to Southern Thailand. For the Thais, cooperation with the Malaysian authorities is needed while dealing with the separatist insurgents that often slip across the porous border from Thailand. On the Malaysian side, sharing the same ethnicity and Islamic religion as the Southern Thai Muslims means their politicians ought to have a key role to play in understanding and resolving insurgency issues in Southern Thailand. It might therefore seem logical that without the help of the Malaysian government, issues in regards to Muslim separatist moments in the deep South would be difficult to resolve. So when the report of a peace dialogue was made in February 2013, it came as a surprise for many.

The announcement of the peace dialogue between the Secretary-General of Thailand’s National Security Council (NSC) and the representatives of the well-known separatist movement Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN) on February 28, 2013 was a bolt from the blue. The location of the announcement was also significant, it tells us a lot about the formation of the historic meeting of the two hostile parties. The news was announced by the Malay Prime Minister, Najib Razak in the capital, Kuala Lumpur, following talks with Thai Prime Minister, Yingluck Shinawatra.

Amidst the ongoing campaign of daily violence in the area, the first public news of an attempt for a peace dialogue by the Yingluck government was unexpected. From the rumor mill there had been reports of meetings between the Thai army and separatist leaders but there had been no official engagements reported. The Prime Minister herself, Yingluck Shinawatra, seemed to be steering the negotiations. She is the sister of a former prime minister, the ‘controversial’ Thaksin Shinawatra, who now lives in exile. Thought to be a mere proxy for her exiled brother and with little political experience, seasoned political movers thought Yingluck would be a pushover in the rough and tumble of Thai politics. Yet she settled comfortably into her role. Her novice government, Pheu Thai (For Thais Party), found its feet despite the heavy opposition mounted by the Democrat Party and the well-organized anti-Thaksin movements including the powerful People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD), known as the Yellow Shirts. Instead of the new government crumbling as many had thought, Yingluck showed some deft political footwork and we are now witnessing a sudden turn-around in the approach in handling the political conflict in the South. For the moment at least, it seems that the Thai government is coming to terms with this reality of what until now has been an intractable problem.

Legacy of Thai nation-state building

Looking back at the handling of the Malay Muslim South by past Thai governments, it is clear that the methods and strategies employed have been swayed by political expediencies. Yet this is not a modern phenomenon; it has long been the case with the South of Thailand. Looking back a hundred years, unable to resist the pressure from Great Britain to rule over the Malay states, Siam, in 1909, finally decided to cede the four Malay states of Kedah, Kelantan, Trengganu, and Perlis to Britain. In return, the British acknowledged Thai sovereignty over Patani and Satun. Earlier Siam had already initiated the administrative reform movement of the whole kingdom. The centralization of the Thai kingdom came with the idea of a Thai nation-state in which all ethnic differences were erased. After that, the subjects of Lao, Cambodian, and Malay ethnicities in the former tributary states were all labeled Thai. Earlier in 1901, Siam had ignored the ethnic and cultural differences between the inner provinces and the seven Malay states and changed their collective names to that of the Area of the Seven Provinces [Boriwen Chet Huamuang]. They were no longer either autonomous or dependent states but provinces under the direct rule of the government in Bangkok. Yet, in 1902, the raja of Patani resisted giving over to Bangkok what he felt was his rightful and traditional power. In a heavy-handed move, he was arrested and swiftly incarcerated in Phitsanulok, a Northern Province; this was done to douse any feelings of uprising in other Malay states.

The historical significance of these actions is interpreted in different ways on the Thai and Patani side. The 1901 incident is accounted by Thai history as a revolt [kabot], while the Patani raja note this as resisting of the coming of modernization. Patani intellectuals have a stronger view. They believe Siam used all sorts of trickery and deceit to deceive the raja and the Malay people in order to fall under the yoke of Siamese subjugation, and accordingly, 1902 was the loss of their rights to freedom and independence. With the modern Thai interpretation of history, most Thais believe that the deep South has been and still is Thai territory, and this implies that issues in regards to security must be dealt with exclusively by their own government.

The new development of the contentious histories between Siam and Patani came in 1938, when Field Marshal Phibun came to power and began to implement a policy of Thai nationalism as part of his nation-building campaign. The government enforced the National Culture Act in which the most sensitive part was known as ratthaniyom, or the State Decrees. According to these laws, all Thais had to wear proper dress, and express modern behavior and etiquette when appearing in public places. In practice, it meant that Muslims could no longer carry their names in Malay or Arabic or dress in their Malay sarongs or headdresses. Moreover, they were required to use the Thai language for education and government offices. Finally, the use of the sharia court in the deep South was outlawed and replaced by Thai judicial courts.

It should be noted that through the forced assimilation of all minorities in the country, the Thai state managed to utilize Thai popular nationalism to serve the purpose of creating a mono-ethnic state. Yet, the era of forced assimilation ended with the popular resistance of Patani people and their religious leaders, the most famous among them was Hajji Sulong, who was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment for the offense of sedition within the kingdom. In general, relations between the Malay Muslims of the deep South and Thai authorities have changed little since. The major components of mistrust, condescension, and misunderstanding are still prevalent among government officials. Fear, resentment, and disapproval of Thai rule and power are also as common among Malay Muslims.

Responding to the growing separatist movement

Successive Thai governments have tinkered with numerous policies aimed at integrating and assimilating the Muslims. By the 1960s, the Thai government embarked on the road to development following advice and funding from the World Bank. At the same time, political separatism became an accepted norm among many Malay Muslims in the deep South. The government introduced development policies aimed at raising the social and economic conditions of the Malay Muslims, hoping that they would be convinced of the Thai government’s good intentions. Consequently, the national development policy became a divisive issue within Malay Muslim society. Modernity benefited some but it also weakened the social values and cultural institutions that had long served as pillars to resist the Bangkok government’s penetration into Malay Muslim society. Thus, there was a radicalization of the pondok that turned out to be a new contending ground between the Thai state and the Malay Muslim identity. The resistance this time by some religious leaders and younger Muslim activists led to the emergence of violent separatist organizations rallying under the banner of radical Islamic principles. Many armed organizations and fronts such as Barisan Nasional Pembebasan Patani, the Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN) and the Patani United Liberation Organization (PULO) sprang up, and the politics of the Islamic community were no longer domestic in the traditional sense, but became internationalized.

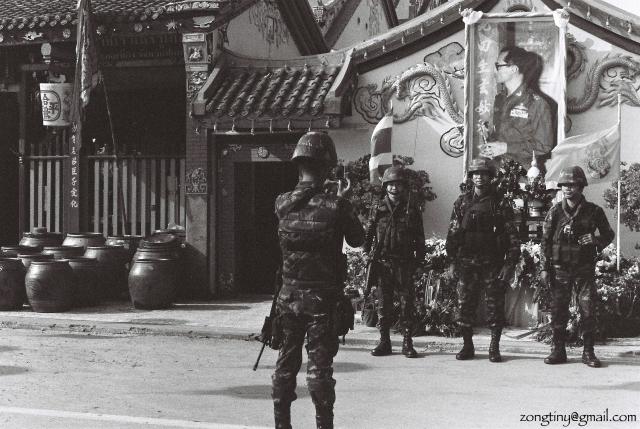

The Thai government, which was determined to pacify and modernize the deep South from above, created the Southern Border Provinces Administrative Center (SBPAC), an organ of administration in order to coordinate all programs and funding. The number of government departments and agencies, including security and armed forces, created to bring the whole region under the control of the government was higher than in any other regions of the country. The ‘success’ of the many peacekeeping commands resulted in arrests of a number of local Muslims, and large numbers of these spent years in protracted trials, that is if they were tried at all, and eventual acquittal by the courts. In the 1980s the SBPAC was able to normalize and bring peace back to the region by dismantling all armed struggles, including the Thai Communists and the Malay separatist movements. In the 1990s, violence in the Muslim South was minimal and did not threaten state security in the area. Separatism seemed to be a ghost of the past. However, by the beginning of the 21st century, the situation in Southern Thailand was changing dramatically.

The start of ‘daily killings’

The peaceful interregnum was terminated in January 2004, when new waves of militant Muslims opened up their armed struggle with the attack of the army camp in Narathiwat, killing four soldiers and escaping with more than 400 rifles and machine guns. The militants also torched 20 schools in 10 districts in Narathiwat at the same time. All the soldiers executed were Buddhists while their Muslim colleagues were spared. As might be expected, the government stepped up its security measures in the area, resulting in the oft-screaming headline of “daily killings.” On April 28, 2004, the killings escalated. The shocking incident occurred in the Krue Se Mosque, an important historic place in Patani, when all 37 militant Muslims holed up in the mosque after raiding police and military outposts, were killed by the armed forces. The violence continued in another, but unrelated, incident in Takbai, Narathiwat province, when local people were demonstrating outside the police station against the jailing of Muslim suspects involved in violent cases in the area. They were rounded up by military forces and piled into army trucks to be transported to camps in Songkhla. When the trucks arrived many hours later, 86 Muslims had died due to suffocation.

Since the upsurge of deadly attacks by Muslim militants over the period from 2004 to 2013, the situation in the deep South grew from bad to worse with victims totaling 15,578, of which 9,961 were wounded and 5,617 dead. Even though government personnel, including non-security officials and teachers, were the main targets of militant attacks, many local residents, especially Muslims, also suffered loss of life.

Following the coup in 2006, which toppled Thaksin Shinawatra’s elected government; the interim government under General Surayud Chulanont, former army commander and Privy Councilor, offered his apology for the past heavy-handedness of Thai governments in the treatment of Malay Muslims in the South. However, the response from the militants was not positive. In the meantime, security levels and operations were not reduced as the government continued to apply the Emergency Decree in the area. This gave exclusive power and impunity to the security forces in handling Muslim suspects. Many hundreds were arrested and locked up in army camps for interrogation and re-education programs.

The Seven Pleas… and beyond?

It took more than six decades before the Thai government decided to talk face-to-face with the separatist movements in the Malay Muslim southernmost provinces. But looking back, the first negotiations between the government and the representatives of the Malay Muslims were organized in April 1947. The main ideas and objectives of the Patani People’s Movement led by the charismatic modernist Islamic leader, Hajji Sulong, were presented in the form of Seven Pleas:

- 1. The government of Siam should have a person of high rank possessing full power to govern the four provinces of Patani, Yala, Narathiwat, and Satul, and this person should be a Muslim born within one of the provinces and elected by the populace. The person in this position should be retained without being replaced;

- 2. All of the taxes obtained within the four provinces should be spent only within the provinces;

- 3. The government should support education in the Malay medium up to the fourth grade in parish schools within the four provinces;

- 4. Eighty percent of the government officials within the four provinces should be Muslims born within the provinces;

- 5. The government should use the Malay language within government offices alongside the Siamese language;

- 6. The government should allow the Islamic Council to establish laws pertaining to the customs and ceremonies of Islam with the agreement of the (above noted) high official;

- 7. The government should separate the religious court from the civil court in the four provinces and (give the former) full authority to conduct cases.

The first plea/demand was about the nature of political relations between the Malay Muslims and the Thai state. It essentially called for a review of the political status of the Malay Muslims in the South and that their rightful place in the modern Thai nation-state were as equal citizens with distinctive rule and government. Other demands demonstrated their desire for respect and equal treatment for the Malay ethnicity and Islamic practice. The then-government of Thamrong rejected the pleas saying they were a return to the previous old sultanate kingdom in which the power to rule resided in one person. At that time, the concept of autonomy and self-determination was rarely heard in the Thai political discourse. The key concept was (and still is) a unified one nation-state based on Thai nationalism. In the 1940s, when the country was facing the imminent threat from Western powers, a centralized state and unity based on a dominant ethnic group was more satisfactory than a decentralized state and administration.

The first peace dialogue between the government and the Malay Muslims ended after the military coup in 1947. In 1948, Hajji Sulong was arrested by the government installed by the coup, led by Prime Minister Khuang Abhaiwong, the head of the Democrat Party. Hajji Sulong was charged with sedition and rebellion against the Thai state. The Patani People’s Movements were regarded as terrorists and rebels. Since then, the Thai government has adopted more severe governing measures of the area and has imposed policies aimed at assimilating the Malay Muslims into the dominant Thai culture and identity.

BRN’s Five Points Proposal

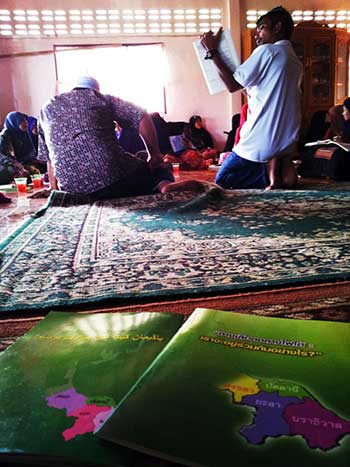

Given the historical background of the relationship between the Thai government and the Malay Muslim political movements, we can discern certain issues that the BRN regarded as important and crucial to their legitimate existence and struggle. After the first initial meetings and dialogues between the BRN and the NSC, both sides tried to gain an understanding from, and trust of, the other. The dialogue was part of a process of searching and finding some kind of common roots and understanding. Soon the BRN was confident to present their political aims and objectives. By looking at the proposed five demands of the BRN, I can see the shadow of history in the making. Here is the list of the key issues to be negotiated with the Thai government.

- 1.The government must recognize the BRN as the representative of Patani people and a liberation organization and not a separatist movement. Liberation means the right and freedom to practice religious activities, to pursue a Malayu way of life without oppression and attack by the authorities.

- 2.The status of Malaysia should be changed from the facilitator to the mediator in the peace process. If this is accepted by the government, the BRN promises to stop attacking security forces tasked with providing protection to teachers.

- 3.Future peace talks must be witnessed by representatives of Asean countries, the Organisation of Islamic Conference and non-governmental organizations.

- 4.The government must recognize the statehood of Patani and the sovereignty of Patani Malays. The southern conflict stemmed from Siamese occupation of the Patani state and violations of human rights. The Patani Malays should have a chance for self-determination to administer their territory in the form of a special administrative zone within the Thai Constitution.

- 5.All suspects held on security-related charges must be released and all arrest warrants invalidated. If this demand is accepted, the BRN agrees to lay down their arms.

In the explanation attached to the Five Points Proposal, the BRN clarified each point both on the grounds of the political system of the nation-state, in which minorities have certain rights and equality with the majority as citizen of the country, and of history in which both Bangkok and Patani have endured a long relationship. The key issue, which has to do with the histories of the two sides, is independence and free citizenship of the Malay people. By asking for the recognition of Patani’s sovereignty, the Muslim separatists demonstrated their steadfast call for the re-interpretation of Siam’s annexation of Patani in 1902. This point will be the most difficult fact for both Thai government and the Thai people to accept. But the representatives of the BRN also said that Siam (meaning the Thai government) does not need to accept whatever they propose. They are asking: Simply listen and demonstrate the Thai government’s position and understanding of the issues. If both sides, at least, could agree to live together in peace despite their disagreement, that might be the new positive sign of the coming of peace in the deep South.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the articles in P’s Pod are personal views of the authors and do not represent views or positions of particular institutions, organizations, groups or parties, including those of the authors and the universities of P’s Pod editorial team, unless otherwise stated.

All the photos in this articles, and many others on the site are from wewatch.info. Please visit the site for more on Thailand’s Deep South.

Professor

Pridi Banomyong International College

Thammasat University, Bangkok, Thailand

October 21, 2013