- SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES

Indigenous Peoples (Lumad) in Mindanao-Sulu Affected by the GPH-MILF Peace Process

Allow me to go directly to the topic—

Who among the Indigenous Peoples, all more popularly known as Lumad in Mindanao, are affected by the peace process between the Philippine Government (GPH) and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), the Manobos of Cotabato and the Teduray-Lambangian-Dulangan Manobo of Maguindanao? The latter is already an integral part of the Autonomous Region in Mindanao Muslim (ARMM). Adopted from the Bisayan word meaning indigenous or native, Lumad, as their collective name was announced in 1986, along with their right to self-determination within their respective ancestral domains; representatives from 15 tribes took part in the decision. Why Bisaya and not their local names? Among the Lumad, Bisayan happens to be their lingua franca in all their intertribal assemblies, more than 30 tribes of them. Today, those who are affected by the GPH-MILF peace process openly acknowledged the legitimacy of the Bangsamoro assertion but they also clearly state that they are distinct from the struggle of the Bangsamoro, especially those who are located within the Bangsamoro territory, as listed down below.

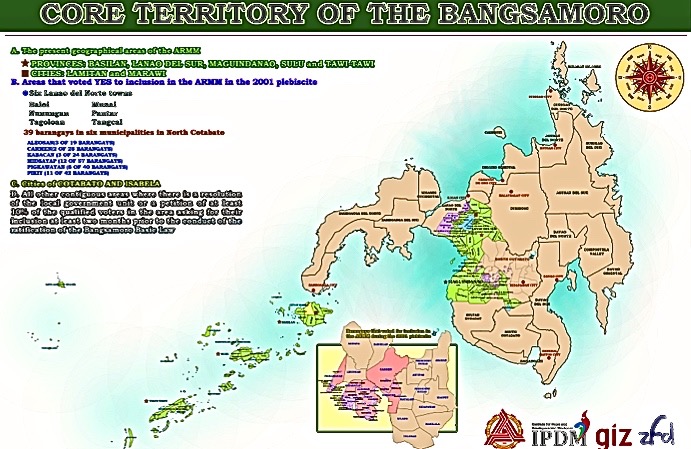

The Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro has clearly laid down the Core Territory of Bangsamoro, composed of the following, and who among them are affected:

a.the present geographical area of the ARMM;

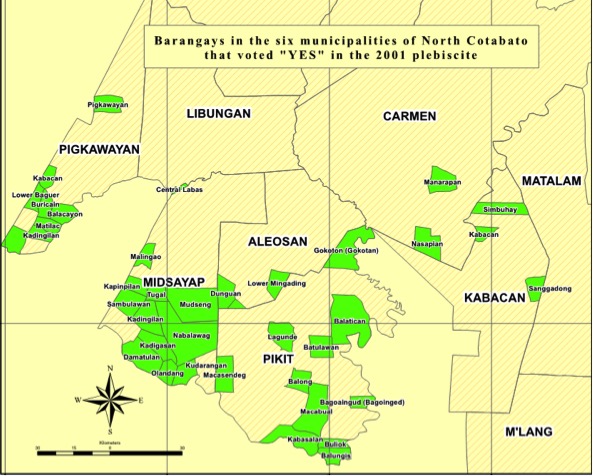

b.the Municipalities of Baloi, Munai, Nunungan, Pantar, Tagoloan and Tangkal in the province of Lanao del Norte and all other 39 barangays in the Municipalities of Kabacan, Carmen, Aleosan, Pigkawayan, Pikit, and Midsayap in the province of Cotabato that voted for inclusion in the ARMM during the 2001 plebiscite;

c.the cities of Cotabato and Isabela; and

d.all other contiguous areas where there is a resolution of the local government unit or a petition of at least ten percent (10%) of the qualified voters in the area asking for their inclusion at least two months prior to the conduct of the ratification of the Bangsamoro Basic Law and the process of delimitation of the Bangsamoro as mentioned in the next paragraph.

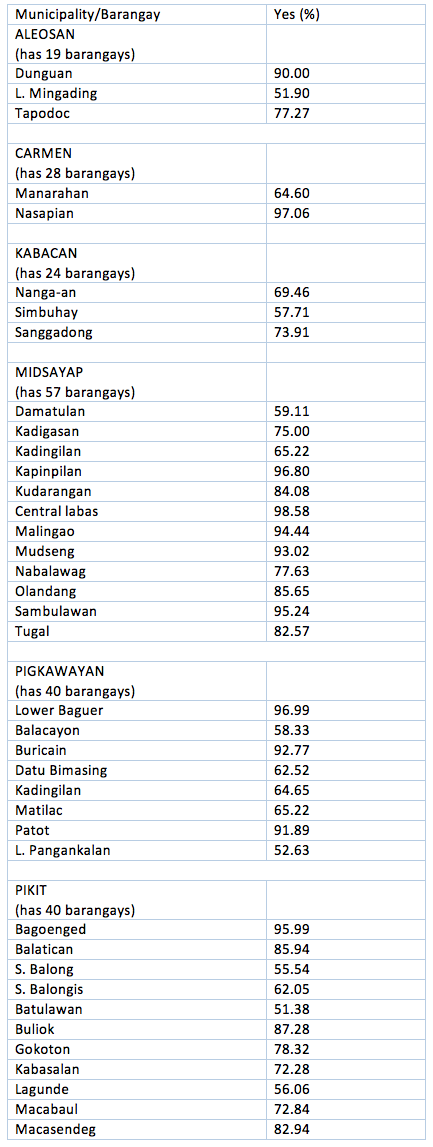

Table 1. Barangays in the six municipalities of (North) Cotabato that voted YES in the 2001 plebiscite

Source: Rudy B. Rodil, Initial comments on the provision on territory in the Framework Agreement between the GPH and the MILF, Oct 2012.

Map 1: Core Territory of the Bangsamoro:

Source: IPDM-GIZ and GFD, MSU-Iligan Institute of Technology, Iligan City.

Map 2: The 39 Barangays in the Six Municipalities, North Cotabato:

Source: Miriam Coronel Ferrer, The Political Settlement With The Bangsamoro Compromises & Challenges. Powerpoint presentation at the Department of Political Science, University of the Philippines, January 30, 2013.

Source: Miriam Coronel Ferrer, The Political Settlement With The Bangsamoro Compromises & Challenges. Powerpoint presentation at the Department of Political Science, University of the Philippines, January 30, 2013.

Constitution considered

Do we consider as resolved the territory issue with addition of these six municipalities? Yes, it seems settled, for the moment. Does this satisfy the constitutional meaning of “geographical areas” in the 1987 Constitution? Article X, Section 15 of the 1987 Constitution says: “There shall be created autonomous regions in Muslim Mindanao and in the Cordilleras consisting of provinces, cities, municipalities, and geographical areas sharing common and distinctive historical and cultural heritage, economic and social structures, and other relevant characteristics within the framework of this Constitution and the national sovereignty as well as territorial integrity of the Republic of the Philippines” (underscoring supplied).The answer is, yes.

This decision to zero in on the barangays that said “yes” in the 2001 plebiscite is obviously a political compromise—because there are 90 other Muslim-majority barangays and 13 more with Muslim population ranging from 40 to 50 percent, “sharing common and distinctive historical and cultural heritage.”

Which Lumad Communities are directly affected?

At least two Lumad communities, the Manobos in North Cotabato and the Teduray-Lambangian-Dulangan Manobo group, are in Maguindanao.

The Manobos are traditional inhabitants of that portion of Cotabato from Pigcawayan to Mt. Apo. This includes the six towns of Aleosan, Carmen, Kabacan, Midsayap, Pigkawayan and Pikit. These municipalities are part of the traditional territories of both the Manobo and the Maguindanao Moros, both of whom affirm common ancestry in the brothers, Tabunaway and Mamalu; the former became the ancestors of the Maguindanao (Muslim) and the latter became the ancestors of the Manobo. A similar story appears in the oral history of the Maguindanao and the Teduray. They have been there since time immemorial. But by a twist of historical events, they have become the minorities in these towns, a direct consequence of government-sponsored resettlement programs from the American colonial period to the subsequent influx of migrants from Luzon and the Visayas under the Republic (of the Philippines). At present, the population of Mindanao-Sulu is roughly distributed as follows according to the 2000 census: Lumad – 8.9 percent; Moro (Muslim) – 18.5 percent, and Migrants and their descendants – 72.5 percent.

How many Manobos are affected?

According to the same 2000 census, although Aleosan reports 463 Lumad inhabitants, Barangays Dunguan, L. Mingading and Tapodoc do not have a single one of them.

Barangays Manarahan and Nasapian, too, of Carmen have reported zero Lumad population.

Barangay Simbuhay of Kabacan has 192 Lumad inhabitants or 12.93 percent of the population, and coming next is Sanggadong with merely six persons. The third, Nanga-an, has zero Lumad population.

In Midsayap only Barangay Tugal has 10 Lumad population, another barangay has two, another still has one. All the rest have zero Lumad population.

Pigkawayan has barangay Kadingilan with six Lumad persons, Buricain has one, the rest has none.

Pikit has barangay Balatican with only one person and all the rest zero.

This means that only barangay Simbuhay of Kabacan has a sizeable Manobo population. What will be the reaction of the Manobo population, as part of the core territory? What happens to the early assertion of the Lumad since 1986 that

The Tedurays, Lambangian and Dulangan Manobo

The Tedurays are traditional inhabitants of that vast territory that used to be labeled in earlier maps as the Tiruray Highlands (as spelled at that time), part of Cotabato City and south of this; the accepted name of the inhabitants today is Teduray. The Tedurays, along with their blood relatives, the Lambangian and Dulangan Manobo, are wedged right in the midst of the Maguindanao world. More than 80 percent of their total population in Mindanao of 71,154 (2000 census) is found in the province of Maguindanao (57,296), mostly in the towns of Upi (24,650) and South Upi (17,559); populations of more than five thousand each are also living in Datu Odin Sinsuat (6,846) and Shariff Aguak (5,801).

They have long wanted to file their ancestral domain claim like their brothers elsewhere in Mindanao, Visayas and Luzon, but the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act does not apply in the ARMM. Neither has the ARMM Legislative Assembly enacted an ancestral domain law. In short, there has been no law in the country that could help them secure their ancestral domain claim. It is a good time to ask at this point: Can they pursue their ancestral domain claim within the Bangsamoro? They have also worked very hard to document their customary laws and strengthen their traditional structures so that in time they can properly govern themselves, within the Bangsamoro Basic Law.

It is important to consider that there are factors, historical and traditional, that bind them between the Lumad and the Moro communities. The following tribes acknowledge that they have common ancestors and their ancestral territories are neighbors: the Teduray and the Maguindanao, the Manobo and the Maguindanao, the Bla-an and the Maguindanao, the Higaunon and the Mrenaw, and the Subanen, Teduray, Maguindanao, Mrenaw. They have also had conflicts and they have arrived at resolution, including clearer territorial borders; these agreements have not expired.

Their differences in identities arose when Islam arrived. Those who adopted Islam developed social structures that eventually gave birth to the sultanate of Sulu in the west and the sultanate of Maguindanao in central Mindanao, while those who remained in their indigenous beliefs continued their customary laws. As far as the Lumad communities are concerned, their identity and right to self-determination should be respected in the Bangsamoro Basic Law.#

Rudy Buhay Rodil

Rudy Buhay Rodil is an active Mindanao historian and peace advocate. In 1988 he was a commissioner of the Regional Consultative Commission in Muslim Mindanao which helped Congress draft the Organic Act for the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao. As an acknowledged expert on the history of the Moro conflict, he was twice member of the GRP peace negotiating panel in the talks with the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), 1993-96, and also vice chair of the GRP Panel in the talks with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), Dec 2004 to 3 Sep 08. He was Visiting Professor at Hiroshima University in Oct-Dec 2011. Having started his studies on Mindanao, especially on the Moro and Lumad affairs, in the summer of 1973, he has so far written four books, several monographs and 127 articles. As educator, he has taught in Sulu, Cotabato, Davao, Manila and Iligan. Now retired, he was professor of history in the last twenty-four years in Mindanao State University-Iligan Institute of Technology, Jun 1983 to Oct 2007. As peace advocate, he has so far participated as resource person in more than 726 forums, seminars and conferences related to the creation of a culture of peace in Mindanao, both in the Philippines and abroad.