For the past three years, the acronyms FAB, CAB and lately, the BBL encapsulated key points in the rough road characterizing the peace talks between the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and the Government of the Philippines (GPH). FAB, CAB and BBL stand for Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro, Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro, and the Bangsamoro Basic Law respectively.

Considering the Filipinos’ proclivity to use acronyms—from the meaningful to the outrageous—this is nothing new and remarkable. But in the case of the MILF-GPH peace process, these acronyms have taken on significant meanings, not only in the literal sense, but also in identifying important landmarks—checkpoints and chokepoints—in the rugged road to peace in Mindanao, especially in the Bangsamoro.

On October 15, 2012, the panels of the two parties signed the Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro (FAB), and this elicited wide euphoria on the looming positive outcome of the long drawn-out process. The MILF talks with the Philippine government commenced more than 17 years ago, spanning the administrations of at least three Philippine presidents: Joseph Estrada, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, and starting June 2010, Benigno S. Aquino III. Public enthusiasm and excitement over the imminent closure of such a tedious and circuitous peace process was palpable, not only in the core territories of the envisioned Bangsamoro, but also in the contiguous and even in other regions in Mindanao and in many parts of the country. For some civil society leaders, just the mention of the word “Bangsamoro” by the President in a statement read on national television was enough to move them to tears. After all, it was the very first time a sitting president of the Philippines, a predominantly Catholic country, would recognize on national television the existence of a separate and distinctive identity of the Bangsamoro.

The FAB led to the creation of the Bangsamoro Transition Commission (BTC), through Executive Order (EO) 120 that President Aquino signed as early as December 2012. It was tasked to draft the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL), the organic act that would create and provide guidelines for the workings of the envisioned Bangsamoro government that will replace the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) by 2016. As EO 120 provided, the BTC was composed of 15 members, 8 of whom were nominated by the MILF; the rest were nominated by the Philippine government. It was also President Aquino who signed the appointment of all BTC members.

ARMM as failed experiment

For more than 20 years since its creation, the ARMM has been the poorest region in the country, with its provinces occupying the bottom rungs of the Philippine’s human development ladder. The original four provinces that constitute the ARMM—Maguindanao, Lanao del Sur, the island provinces of Sulu and Tawi-Tawi—have always been tagged as members of the country’s “Club 20” (the “club” of poorest provinces in the country). After a plebiscite in 2001, the ARMM expanded to include the island province of Basilan and the city of Marawi, a city in Lanao del Sur province, courtesy of Republic Act 9054 (An Act expanding the coverage of the ARMM, and other purposes). Like the original members, the two additional areas also exhibited the same low levels of human development indices compared to other provinces in the country.

From 2006 to 2012, encompassing three periods of the national government’s triennial household census, the region exhibited only one instance when its poverty incidence dipped, although just by a fraction of 1 percent (from 40.5 percent in 2006 to 39.9 percent in 2009). But such a minuscule drop was wiped out with a whopping 8.7 percent increase in the next census in 2012, when its poverty incidence was reported at a very high 48.7 percent (roughly half the number of people in the region) classified as living below the poverty threshold. In actual numbers of families, this percentage translates to 271,355 families, and if this is calculated using the average number of individuals per household of 6 (2 parents and 4 children) – this is roughly 1,628,130 individuals. As of 2012, the total population of the region was a little over 3 million. 1 See Table 1 below for details.

Table 1. Poverty Incidence and Magnitude of Poor Families in the ARMM, 2006, 2009 and 2012*

Region/Province |

Poverty Incidence among families (%) |

Magnitude of poor families |

||||

| 2006 | 2009 | 2012 | 2006 | 2009 | 2012 | |

| ARMM | 41 | 40 | 49 | 205,834 | 212,494 | 271,355 |

| Basilan | 28 | 29 | 49 | 14,137 | 14,787 | 16,832 |

| Lanao Sur | 39 | 49 | 67 | 51,408 | 68,770 | 100,946 |

| Maguindanao | 46 | 43 | 55 | 70,665 | 67,899 | 87,800 |

| Sulu | 35 | 36 | 40 | 39,478 | 42,530 | 51,278 |

| Tawi-tawi | 50 | 29 | 22 | 30,146 | 18,518 | 14,999 |

*Culled from the Regional Development Plan in the ARMM Updates, 2013. p. 22.

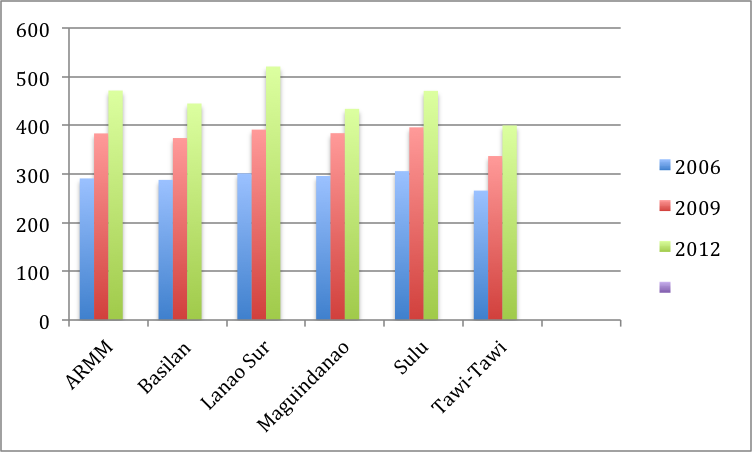

In terms of annual per capita poverty threshold, the amount (in US dollars) is quite measly, ranging from US$266 to$400 (see Figure 1 below). The increases in the per capita poverty threshold are dictated by inflationary factors extraneous to the region. In other words, these are not the results of decreasing poverty incidence.

A significant decrease in poverty incidence was recorded in the island province of Tawi-Tawi from 2009 to 2012, at almost 20 percent from its original level of 50 percent in 2006. But this lone outstanding performance dimmed in comparison with the increasing number of poor families in the four other provinces in the region. Two provinces—Maguindanao and Lanao del Sur—figured prominently in the significant spikes in their poverty incidences, with an average increase of 15 percent from their 2009 records (43 percent to 55 percent and 49 percent to 67 percent respectively, in 2012). The two provinces are also the location of several pocket wars and skirmishes classified as horizontal conflicts. Such conflicts are popularly referred to in the literature as “rido” or vengeance fighting among rival political families or among families that have been engaged in grudge relationships for several years now. 2