- MYANMAR

Evolving Challenges in Myanmar’s Political Transition

The current government that was elected in 2010 has managed to bring about a good measure of internal political reconciliation and liberalization. However, it continues to face major political as well as socio-economic challenges. Overcoming these challenges is important during this period of political transition as the country gears itself for the next election, scheduled to be held in late 2015.

Major reforms of the new government

The Thein Sein government has undertaken wide-ranging reforms since it was elected into office in 2010. Most of these efforts are aimed at enhancing the government’s political legitimacy internally and externally. Deflecting and coopting domestic challenges to its political legitimacy has earned the government much recognition, including from its strongest detractors. The major political achievements include its conciliatory efforts towards the political opposition and the signing of peace treaties with almost all of the ethnic insurgent armies.

Aung San Suu Kyi’s change of heart to compete in the April 2012 by-elections was significant since it brought the government and its opposition, the National League for Democracy (NLD), closer together in terms of finding a political solution to the previous impasse. Thein Sein’s accommodative approach towards Suu Kyi and the NLD was truly revolutionary and an important turning point in the evolution of the country’s political situation

There were a number of other political decisions undertaken by the Thein Sein government that has led to a much more liberal political environment. Prior to the by-elections, the government freed a large number of political detainees. This was one of the major demands of the political opposition as well as Western countries for the lifting of sanctions. Correlated to the decision to free political prisoners was the government’s decision to grant a broad based amnesty to political exiles living abroad. And there were a large number of exiles living in India, Thailand and the West that had previously provided information and organized activities against the military government.

—MPC and Ethnic minorities

The Myanmar Peace Center (MPC) that was inaugurated in October 2012 in Yangon currently serves as the government’s vehicle for negotiating meetings with the ethnic armed groups in order to achieve long-term accommodation and resolve the issue of having private armed groups within the country. President Thein Sein was one of the early architects and supporters of the process to engage the ethnic insurgent groups in the peace process. The MPC’s most significant and important mandate is the conclusion of a nationwide ceasefire deal with all the ethnic insurgent armies. The government has been quite successful in this regard by bringing into the fold the 3 last such groups to sign ceasefires in 2012. These were the Chin National Front (CNF), Karen National Union (KNU) and the Karenni National Progressive Party (KNPP). On the other hand, however, it has suffered a setback with the breakdown of the ceasefire agreement with the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO) and its armed wing, the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) since June 2011.

Images: Chin National Front, Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Chin-National-FrontArmy/163071607069642

The MPC and Thein Sein government’s approach to the ceasefire negotiations is to consolidate the ongoing process at three levels. In the first instance, the ceasefire will be negotiated at the regional level. Subsequently, the agreement will be endorsed at the state level, in accordance with the geographical and administrative division of the country. Finally, all the ceasefire groups will convene a meeting with the government where a nationwide ceasefire agreement will be signed. The last stage of the agreement is meant to replicate the historical Panglong Agreement that was signed by General Aung San (Suu Kyi’s father) in 1947 with the ethnic groups.

It is hoped that afterwards, through an admixture of negotiations for political rights and accompanying development in the region, the armies would be disbanded. These agreements have come with very strong commitment on the part of the government and the able leadership exercised by the lead negotiators of the two government-appointed teams. Especially significant in this regard is the role played by U Aung Min. Their direct appointment by President Thein Sein and their conciliatory approach has won them much leeway and goodwill from the ethnic armed groups who, with rare exceptions, have gone on to sign ceasefire agreements.

—Civil society issues

Another major development in Myanmar politics has been the active role of civil society organizations that have undertaken wide ranging activities, from political education to providing relief for those affected by natural calamities. For a long time, the previous military government was suspicious of such organizations for fear that they would serve as beach heads for foreign interference in the country’s domestic politics and sought to suppress them. The military was particularly suspicious of civil society organizations that received foreign support and funding. That view began to change after the devastation wrought by Cyclone Nargis and the overwhelming task of dealing with the death and destruction.

As for censorship of the mass media, authorities often had to physically clear what appeared in print in the past. As a result of such scrutiny, the major daily English language newspapers were only the government sponsored and propagandistic New Light of Myanmar and the Myanmar Times. Then there were weekly journal type magazines that were also heavily censored. Censorship rules were strict and entire articles could be ruled out of line and the journalists could be imprisoned or subjected to other sanctions. Hence the community of reporters tended to err on the side of safety. However, the Thein Sein government has lifted press censorship and the mass media operates relatively freely now. This new freedom means that information is now widely available and shared and, as a result, the government has been subjected to far greater scrutiny. There are also investigative pieces that sometimes put senior government officials on the defensive, like in the recent reports regarding the illegal confiscation of land by senior military officers.

When appraising the performance of the current government it needs to be borne in mind that it has only been functioning for little over three years since November 2010. The enormity of the task confronting the government is truly staggering. Even at this time the state does not have full control over all the country’s territory and peoples. The country’s infrastructure is weak and dilapidated and there are no formal laws in many areas, and where these exist they are easily bypassed. Nonetheless there is significant political will at the leadership level in addressing the issues directly and the international community has also offered much support and aid.

The newly evolving challenges

There are a large number of problems that require the attention of the current government of Myanmar. Some of them are more important than others since they impinge on the core functions of governance—the provision of safety and security for the inhabitants of the state. And two issues stand out in this regard. The first of these is the resumption of hostilities between the military and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) in Kachin state. This resumption of hostilities has wider implications for the ceasefire process in general and the government’s attempts to secure a nationwide ceasefire deal. In fact, the ethnic groups have significantly consolidated themselves and now appear to utilize a strategy of bargaining collectively. Additionally, there appears to be a broad-based agreement between the political opposition, the ceasefire groups and civil society groups that they have convergent interests, and that these are best served by working together against the government. In this regard, the government appears to be facing a united front of sorts of disenchanted local groups.

The second major challenge is the outbreak of violence in Rakhine state and, more recently, in Mandalay and Yangon Divisions. Whereas in the case of the ethnic groups there is actual military conflict, the latter can be more correctly described as communal conflict that has pitted two different ethno-religious communities against each other. Nonetheless, both of these developments have tremendous potential to set back the political legitimacy that the current government has sought to amass.

The KIA previously had a ceasefire agreement with the government that unfortunately broke down in mid-2011. The insurgent army has a troop strength of approximately 8,000 and is deployed in Kachin state that shares a long border with China. Both sides have blamed the other for the collapse of the truce. There are now approximately 100,000 internally displaced persons in government controlled refugee camps and another 55,000 in areas controlled by the KIA. The latter is headquartered in Laiza, near the border with China and there have been reports of shells landing on the Chinese side that hosts approximately 5,000 refugees. There have been a number of attempts by the government to resolve the Kachin situation. President Thein Sein issued two Executive Orders for the military to halt the fighting that came to naught in 2012. Similarly, civil society groups and more recently in January 2013 the Lower House of parliament also called for a halt to the fighting. The government has granted access to international relief aid agencies to assist with humanitarian work in the areas under its control.

—Coordination among opposition groups

In February 2011, a total of 11 ethnic armed ceasefire groups that include the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), New Mon State Party (NMSP), Shan State Army – North (SSA-N), Karenni National Progressive Party (KNPP), Chin National Front (CNF), Karen National Union (KNU) and five smaller groups representing the Lahu, Arakan, Pa-O, Palaung and a splinter Wa group, formed the United Nationalities Federal Council (UNFC) in order to collectively coordinate their position with the government. Whereas the general level of trust between the ceasefire groups and the government is quite high, groups like the All Burma Students Democratic Front (ABSDF), Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), Revolutionary Council of the Shan States (RCSS) and the United Wa State Army (UWSA) have not always been agreeable or cooperative, and sporadic fighting has broken out from time in Kachin and Shan states. The groups are also attempting to project a united front in order to have much stronger negotiating terms and positions. The latest development in this regard is the formation of the Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team (NCCT) that was formed in October 2013 after a meeting in Laiza. The NCCT draws its membership and office bearers from the larger ceasefire groups, and has recently been spearheading meetings with the MPC.

Also, in February 2014, the ethnic groups launched the Pyidaungsu Institute (PI) 1 in Chiang Mai, Thailand, to coordinate the position of the different ethnic groups. Office bearers of the PI are also drawn from the major ethnic groups and the stated policy position is to provide a common platform for dealings with the MPC. The ethnic groups’ situation is also complicated by a proliferation of organizations, including the Nationalities Brotherhood Federation that brings together 20 ethnic groups. This group announced in May 2014 that it has prepared a draft for the establishment of a federal union.

The loosened political situation has also led to a surge of civil society organizations, and increasingly many of them are finding common cause to oppose the government. They are especially interested in lobbying the public for amendments to specific provisions in the 2008 Constitution that give the military 25 percent of all seats in parliament and the need for an overwhelming majority of votes in excess of 75 percent in parliament to amend the constitution. As long as the military casts a block vote, such an amendment is impossible. There are also attempts to remove clauses that disqualify Aung San Suu Kyi from holding executive positions in the government, such as the ones that prohibit persons with foreign spouses and children from becoming President and the proviso that the President must be trained in military or strategic affairs. The political opposition and civic groups have found common cause in this lobby. Leading advocates for such change include the 88 Generation Group that was involved in the 1988 democratic protest movement against the military junta and the NLD. In May, there was a demonstration in Yangon that brought 35 such civil society groups together with 3,000 activists petitioning for change. The NLD and the 88 Generation Group has also launched a nationwide signature campaign hoping to persuade the government of the popularity of its position.

—The Rohingyas

The second difficult situation confronting the government is the outbreak of violence between the Rohingya and the Rakhine communities in western Rakhine state. There has always been historic animosity between the two groups and successive Myanmar governments have refused to recognize the Muslim Rohingyas as native to the country. Instead, they are typically referred to as Bengali Muslims and have had strict limitations placed on their personal freedoms, association, property ownership and movement. They are often viewed as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh and number some 800,000 in all.

The Rohingyas appear to have borne the brunt of the violence and those who fled their homes and property are currently housed in refugee camps near the port city of Sittwe. Many from the community have also chosen to flee the country and regularly land in Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia. The issue has also strained ties between Myanmar and Bangladesh with the latter refusing entry to would be refugees arguing that it already hosts 300,000 persons in refugee camps across the border. The violence in Meiktila in March 2013 2 was also aimed at Muslims and appears to have taken its cue from the situation in Rakhine. During this second incident, 43 persons perished and as with the earlier episode, security forces appear to have been complicit in the violence, at least at the outset. Since then similar episodes of violence have broken out in Lashio in the northern Shan states, Mandalay, Oakkan on the outskirts of Yangon and Thandwe in Rakhine State.

As in the Kachin case the Myanmar government has allowed international relief agencies to become involved in tending to the welfare of the displaced Rohingyas. On its part, it has also formed a Commission of Enquiry into the violence that made public its findings in April 2013. Additionally, the government has decided to build more permanent housing to resettle the Rohingyas, but the plan has been met with stiff resistance from the local Rakhine community. The early site of three islands off the coast of Sittwe has been rejected by the Rakhine community. The government is also actively trying to dissipate tensions between the Buddhist and Muslim communities by hosting inter-faith dialogues. President Thein Sein is a keen advocate of these dialogues and they have been occurring quite regularly at the Myanmar Peace Center (MPC) as well.

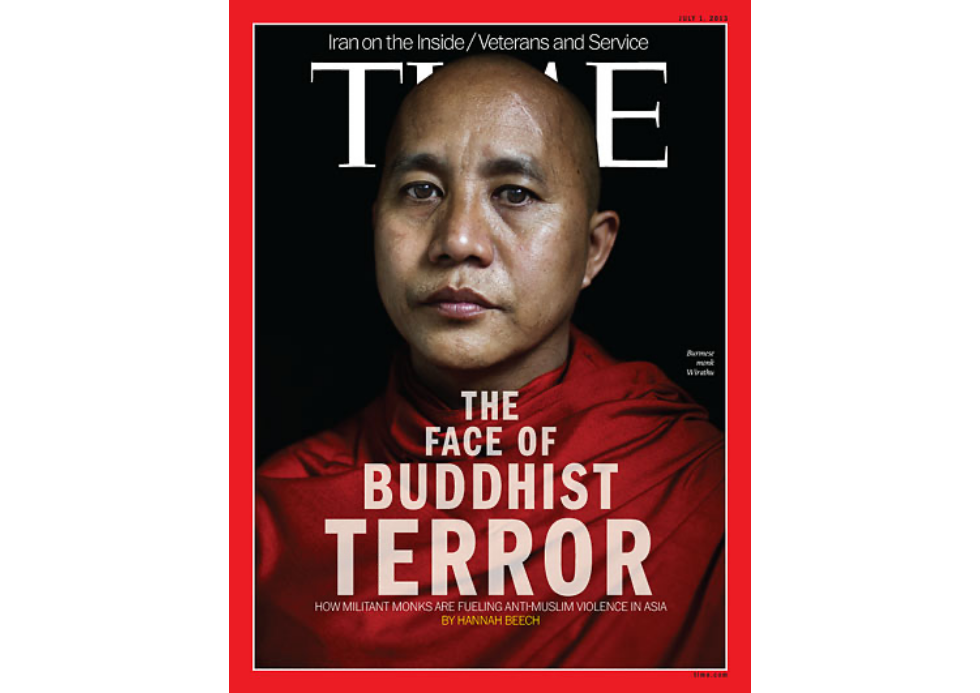

Two developments have significantly complicated this ethno-religious strife. The first of these is the evolution of Buddhist organizations that are specifically devoted towards checking the Muslim religion and its adherents within the country. The movement appears to be centred in Mandalay and led by the firebrand monk Ashin Wirathu. He has utilized the sangha in order to push for restrictions on religious conversion and inter-faith marriages in particular. It is now the subject of Religion and Nationalities Bill that has been sent to parliament for enactment into law. Separately, the monks have also inspired the formation of a social movement called the 969 group, 3 whose avowed intent is to stop patronizing businesses that are owned by Muslims. Such actions that have a tendency to fan hatred and pose a threat to civil harmony has created a major problem for the government that is trying to control outbreaks of hatred and violence.

The second development that complicates the situation is the existence of an insurgent group that is responsible for cross border violence from Bangladesh. This group, the Rohingya Solidarity Association (RSO) is gazette as a terrorist organization by the Myanmar government. It has conducted a series of cross-border raids that has led to significant casualties among members of the Myanmar border police. These clashes have significantly raised the temperature in bilateral relations between Myanmar and Bangladesh. Whereas the Myanmar government accuses Bangladesh of illegally harbouring members of the RSO, the Bangladesh government and Border Guards have flatly denied the accusation. Both sides have significantly beefed up their security presence at the border and the Myanmar government has bluntly indicated that it will repulse such future actions.

Whither from here: 2015 and beyond

There is little doubt that Myanmar is currently in the middle of an historical conjuncture with path dependent tendencies that will draw it away from its past. While the current situation appears to be the culmination of a military-inspired roadmap to democracy that began in 1994, the ongoing reforms are beginning to loosen the country’s political climate. President Thein Sein’s decision to engage Aung San Suu Kyi and other members of the political opposition has changed the situation on the ground. The NLD has clearly made significant progress in establishing itself as a political force to reckon with. It has also galvanized other civil society groups to push for amending the 2008 charter.

The largest and most influential domestic player is currently the military. It is the most organized actor and has disproportionate resources at its disposal in relation to its competitors. Most members of the current cabinet are ranking military officers who have simply donned civilian clothes. The mass based organization that represents their political interests is the USDP, which was simply converted from the previous Union Solidarity and Development Association (USDA). In structural terms, the military has a 25 percent representation in the Union government as well as the regional parliaments. The parliament requires an absolute majority of more than 75 percent in order to amend the 2008 Constitution and the military is likely cast a block vote to veto any prospects of such a change. Additionally, the document clearly forbids those married to foreigners and with children holding foreign passports from holding high executive office and, therefore, Aung San Suu Kyi would clearly be subjected to this rule. On the other hand, Aung San Suu Kyi has lobbied to change the constitution to bring in more in line with the wishes of the people and has made no secret of the fact that she aspires to be the next President. The military is also not subjected to parliamentary oversight and controls Home Affairs, Defence, and Border Areas while maintaining a majority representation of 6 out of 11 members in the National Security Council.

Based on the NLD’s and Aung San Suu Kyi’s popularity in the April 2012 by-elections, it is likely that the NLD will perform spectacularly well in the next national election slated for 2015. However, under the current constitution she cannot become President and attempts to change the Constitution may well prove difficult. Hence it is indeed possible that a compromise candidate acceptable to all parties may emerge as the new President.

In any event, beyond all this epiphenomena, it is really the military and the bureaucracy that is providing continuity and holding the country together. The large numbers recruited into the military’s officer cadet corps in the last decade (up to 2,000 per annum as opposed to the traditional 120) may well vent their frustrations if the military continues to be sidelined and deprived of lucrative placements in the bureaucracy as the political situation evolves. Ne Win and Than Shwe were much more careful with such placements and deflecting the possibility of coup attempts in the past. The failure to deal with the aspirations of the large military cohort down the line will certainly raise the spectre of a coup.

Notes:

- 1. http://www.pyidaungsuinstitute.org/index.php ↩️

- 2. Violent clash between Muslims and Buddhists in Meiktila in Mandalay region in 20-22 March 2013. http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/04/01/burma-satellite-images-detail-destruction-meiktila ↩️

- 3. See also piece on APBI site by Tin Win Akbar, “Recent Religious Riots in Myanmat: the current situation of Burmese Muslims” (17 February 2013). http://peacebuilding.asia/recent-religious-riots-in-myanmar-the-current-situation-of-burmese-muslims/ ↩️

Professor, Hiroshima Peace Institute