- MYANMAR

Recent Religious Riots in Myanmar: the current situation of Burmese Muslims

The story of Myanmar’s transformation from an entrenched military dictatorship to nascent democracy has surprised many observers. However, the violent attacks by Buddhists against Muslims that occurred from the fall of 2012 to the end of 2013 have cast a shadow on these positive developments.

The current conflict between Buddhists and Muslims began in 2012, when a Buddhist woman in Rakhine was found raped and murdered. The blame for this crime fell on the Rohingyas and the Rakhine Buddhists retaliated by attacking a bus and killing ten Muslims. This fighting spread quickly between the Buddhists and the Rohingyas and set off waves of riots and mob violence. With casualties on both sides, most observers agree that the Rohingyas suffered a disproportionately greater loss of life and property. More than 250 people were killed, many more injured, and 250,000 Muslims were displaced, mostly from their homes in the state of Rakhine. Those displaced by the conflict are still in temporary camps today.

In late March 2013, rioters went on a three-day rampage in central Meikhtila, burning down Muslims’ homes, businesses, and mosques, which resulted in the killing of around 40 people. What was left of Muslim-owned businesses were spray-painted with the number ‘969’. The three digits ‘969’ refer to the Buddha’s “three jewels”, the first number ‘9’ represents the nine great properties of Buddha, the second number ‘6’ represents the six great properties of Dhamma (the Philosophies of Buddha) and third number ‘9’ represents the nine great properties of Sanga (Buddhist Monks). The underlying message of ‘969’ is that Myanmar is for Buddhists, particularly for Buddhists who are ethnic Bamar rather than members of other ethnic groups.

Shortly after, riots erupted in the Bago region after travelling monks preached the ‘969’ ideology. In addition, fresh clashes broke out in Oakkan, a town north of Yangon, where at least one person was killed. With no end to the violence in sight, today thousands of Muslims displaced by these riots remain barricaded in refugee camps. As anti-Muslim sentiment spread in the Buddhist-dominated country, violence broke out in a remote city in a mountainous region near Myanmar’s northeastern border with China, about 700 km from the commercial capital Yangon. Then in early October 2013, communal violence erupted between Buddhists and Muslims in Sandoway in western Myanmar, again this resulted in loss of life; five Muslims dead and dozens of homes destroyed.

‘969’ movement and Burmese nationalism

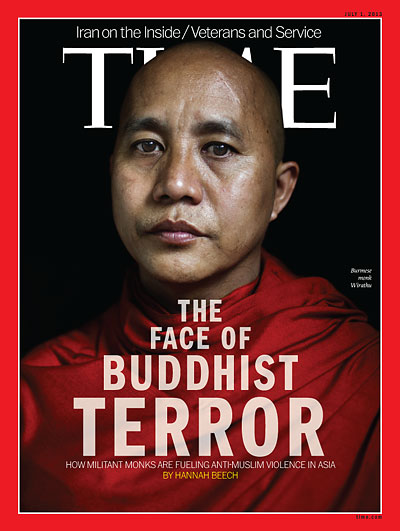

Many observers believe that the Buddhist nationalist-led ‘969’ movement is fermenting or, at the very least, behind a broad range of anti-Muslim activities, including violence across much of Myanmar. It is becoming a brand name for the nationalist anti-Muslim campaign led by prominent Mandalay-based monk, Ashin Wirathu.

Ashin Wirathu was arrested in 2003 for inciting anti-Muslim riots in his hometown near Mandalay, riots in which Buddhists killed ten Muslims. Ashin Wirathu was sentenced to 25 years in prison, but was released as part of an amnesty in 2011, shortly before the latest surge of anti-Muslim activity in the country. Since then, Ashin Wirathu has spearheaded the fast-growing ‘969’ movement, making numerous speeches calling on Buddhists to “buy 969” and boycott Muslim-owned stores. The movement’s ideology combined Buddhist religious fanaticism with intense Burmese nationalism and more than a tinge of ethnic chauvinism. Not surprisingly, the rhetoric struck a chord with the Bamar, the principal ethnic group in Burma, accounting for about two-thirds of the country’s population, and especially prominent in the lowlands of the Irrawaddy Basin. The vast majority of the Bamar are Theravada Buddhists.

Time Magazine. July 1, 2013. Vol. 182, No. 1.Cover image via Time Magazine.

There is also a sense in which 969 is intended as a numerological counter to the Muslim 786 symbol. The number 786 is derived from the numerical value in the Arabic Abjad numeral system of the opening passage of the Koran and is used by Muslims in Myanmar and elsewhere in South Asia as a sign, particular in the case of Islamic halal restaurants. (A groundless yet widespread rumour in Myanmar is that 786—adding up to 21—is a secret Muslim code that indicates a desire to take over either Myanmar or the world in the 21st century.)

As anti-Muslim riots rocked Myanmar, President Thein Sein blamed the carnage on “political opportunists and religious extremists” and issued a warning to those who exploit noble religious teachings for their own self-interest by stirring hatred among people of different faiths. On 4 October 2013, Thein Sein accused “outsiders” of orchestrating the outbreak of Muslim-Buddhist communal violence in Sandoway in western Myanmar, suggesting it was a premeditated attack intended to undermine his first visit to the conflict-torn region. However, he did not make it clear about who were these “outsiders”.

Staged incidents?

Mr. Tomás Ojea Quintana, the UN special envoy on human rights in Myanmar, suspects the involvement of state forces. He said (there are) instances where the military, police and other civilian law enforcement forces have been standing by while atrocities were committed before their very eyes. These acts include violence by well-organized ultra-nationalist mobs who happen to be Buddhists. This may indicate direct involvement by some sections of the State or implicit collusion and support for such actions.

Aung Zaw, a journalist who founded the news organization Irrawaddy Publishing Group, wrote in the New York Times that factions within the government appear to be encouraging the monks to take part in the violence. He stated that the deadly anti-Muslim riots are no accidents but orchestrated by army hard-liners to thwart both Myanmar’s domestic reforms and opening to the world. Hate speech from the hard-liners has influenced many ordinary Buddhists in Mynamar, driving them to violence against Muslims. The Buddhist monks, meanwhile, provide a veneer of respectability to the violence.

Dr. Maung Zarni, a Myanmar exile who is a visiting fellow at the London School of Economics, has critically examined the role of the quasi-civlian Thein Sein government in the recent violence in Myanmar. He has listed a number of overt anti-Muslim acts committed by the government, from backing violence against Rohingyas and “cleansing” Muslims from the Burmese military to approving anti-Muslim publications and bolstering the rise of Ashin Wirathu himself.

Yet religious intolerance is not new to Myanmar, as noted by Andrew Selth at Griffith University, as the regime reportedly encouraged some anti-Muslim riots to divert attention from its own failings before 2011. He points out that the problem is not just the tactics of the security forces but the discriminatory policies and community attitudes in Myanmar, meaning that anti-Muslim unrest is likely to recur. These are issues that few politicians in Mynamar seem willing to address seriously.

Other observers see tacit coordination between the mobs and the government, and suspect the hard-liners are trying to discredit Aung San Suu Kyi. Myanmar expert and author Bertil Lintner said, that the government is very worried about the support that Suu Kyi commands. It wants to force her into a position where she would be forced to make a pro-Rohingya statement that could undermine her popularity among Myanmar’s Buddhists, many of whom harbour anti-Muslim sentiment. Many Burmese appear to approve of the violence in the name of protecting Buddhism. On the other hand, if she remains silent on the issue, she will disappoint those who support her firm stand on human rights.

Fingers have been pointed in different directions, and most seem to Myanmar agree that someone, or some group, is deliberately instigating the recent unrest.

The role of the media

The role of Myanmar’s nascent information culture could be responsible in spreading malicious rumour that has fanned ‘hate speech’. The legacy of state censorship that only ended in August 2012 lingers, and only a few Myanmar nationals have access to news from independent media sources or to the online social media that is ubiquitous in much of Southeast Asia. According to a well-informed source, only around 800,000 people have Facebook accounts out of a population of around 65 million. While 300,000 Myanmar nationals read weekly newspapers, some of the most popular publications show bias against the Muslims. Moreover, the majority of Myanmar’s population hears about political developments from word-of-mouth, family, friends, neighbours or the monks; none are considered reliable of news sources. But to understand the dynamics of the current religious conflict’s deeper causes we need to examine closer the political and cultural situation.

Burmese Muslims: turbulent relations the Burmese Buddhists

Muslims initially arrived in what is today’s Myanmar as traders in the early 11th century from Central Asia and other parts of Southeast Asia. The Muslim population in Myanmar today includes those of Pathis, the oldest settlers since first Burmese Kingdom established at Pagan of Indian ancestry, Pashu (Malay ancestry), Chinese ancestry known as Panthays, Rohinhyas (northern Rakhine), Kaman (Southern Rakhine) and many others of mixed ancestry. There are also Burmese Muslims, either through marriage or conversion. Yet in the eyes of most Burmese and past military regimes, those that become Muslim cease to be Burmese and would likely be classified as Kalar, a derogatory term for Burmese Muslims (originally used for migrant Indians regardless of any religious affiliation) or even just foreigners.

In the 1930s, economic hardship and anti-colonial movement spurred riots that were directed at the immigrant Indian population in general. While the riots in 1938 were anti-colonial they also targeted Muslims more explicitly. After the establishment of the military dictatorship in 1962, however, targeting the Muslims became unambiguous.

Anti-Muslim riots occurred many times throughout the half a century of military rule. Despite the fact that these riots involved large numbers of monks, many presumed that the incidents were organized by military rulers to divert the attention from economic hardship, the failure of policies, or to galvanize nationalist sentiment. Since military leaders were unable to improve the lives of people, Muslims became a convenient scapegoat to shield them from public anger.

Moreover, Muslims were explicitly excluded from the Burmese military, high government office and from many prestigious positions in the country. The route to high education was also blocked to the Muslims. Consequently, many Muslims engaged in small businesses where they did not need higher education or connections with the government. Many formal or informal rules and regulations were also introduced to suppress the Muslims. At the military academies and public officers’ training programmes anti-Muslim indoctrination was part of the curricula. Regardless of their citizenship, treating Muslims like second-class citizens or even non-citizens became the norm in government circles. Muslims became, in short, oppressed and downtrodden people in their motherland.

Although Burmese Muslims were targeted in riots, faced discrimination and continued to be oppressed by the military, they were still able to maintain a healthy, harmonious relationship with the Burmese Buddhists in the early days of military rule. In the distant past, Myanmar’s Buddhists and Muslims lived peacefully together for several hundred years. Burmese Buddhists showed respect toward Burmese Muslims’ Islamic faith and even allowed their daughters and sisters to marry Burmese Muslim men and did not object when their daughters and sisters converted to Islam after marriage. Likewise, the majority of Burmese Muslims who are of moderate faith also participated in the religious events of their Buddhists counterparts. The way of life and cultural identity of the majority of the Burmese Muslims were, in fact, not very different from the Burmese Buddhists. However, the policies of the military rulers toward Burmese Muslims were calculated to create many divisions between the two communities.

International Islamic assertiveness and Burmese Muslims

The military dictators who were obsessed with eliminating all political opponents inadvertently gave favour to the religious leaders of extreme conservative Muslim groups who had little interest in the democratic movement, unlike the moderate Muslim religious leaders who were well integrated into Burmese society. Their views follow closely the school of thought that is a mixture of Deobandi, Tablighi, Jamaat and the Wahhabi movements, views that are vastly different from those held by the traditionally religiously moderate Burmese. As a result, Burmese Muslims are slowly and steadily becoming more conservative and rigid in their religious practice. Many changed their way of dress from typical Burmese style to Deobandi style, keeping the beard, wearing clothes very similar to Indians or Bengalis. The new style religious leaders also imposed many kinds of religious pronouncments that made it difficult for Burmese Muslims to maintain their harmonious social relations with Burmese Buddhists.

By 1987, Myanmar was one of the least developed countries in Southeast Asia due to the military dictatorship’s closed-door socialist economy and mismanagement of the country as well as the rabid nationalism driven by political paranoia that distorted Buddhism. What was once one of most promising countries in the region now faced widespread poverty, scarcity of jobs, and a gloomy future. Such a situation forced many Burmese in general to flee their county, legally or illegally, and risk becoming undocumented workers in neighbouring countries. Many went to Malaysia, a Muslim majority country, others headed to the Middle-East Arab countries to work as unskilled labourers.

There have been frequent reports from these countries that undocumented workers from Myanmar have been treated unfairly. This has encouraged many Burmese Muslims to become more pious in solidarity with their Muslim hosts. Given the discrimination the Burmese Muslims have faced in the past and the fact that they cannot rely on the state to protect them in a crisis, it is also understandable that the Burmese Muslims in Myanmar have turned inward, both in their religious practices and in their social interactions. While a number of Muslim groups have been active in charitable activities beyond their own religious community, the perception among non-Muslims is that the Islamic community is insular and that Islamic religious practice is suspiciously private. These perceptions are also influenced by the global narrative of the “War on Terror”, wherein every mosque or madrasa appears to be a weapons garrison or terrorist training ground, an impression cemented by popular portrayals of Islamic militancy in the international media. The impact of international Islamic assertiveness combined with the promotion of Wahhabis school of thought has forced some Burmese Muslims to shift their loyalty from their nation to international Islamic solidarity.

Burmese Muslims: stateless under the 1982 Citizenship Act.

The right to citizenship is enshrined in various international human rights conventions. However, many Myanmar observers say that Myanmar’s 1982 Citizenship Act, which was issued during the reign of former dictator General Ne Win, is incompatible with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights or with Burma’s legal obligations under international treaties. In addition, they also say that the citizenship act arbitrarily stripped many people in Myanmar, almost all the Burmese Muslims, of the right to citizenship.

Under Article 4 (II) of the previous 1948 Citizenship Law, “Any person descended from ancestors who for two generations at least have all made any of the territories included within the Union their permanent home and whose parents and himself were born in any of such territories shall be deemed to be a citizen of the Union.” However, unlike the previous citizenship law that was introduced at the time Myanmar (then Burma) became independent in 1948, the 1982 Citizenship Act guarantees citizenship only for those who can prove that their families have lived in Myanmar for at least three generations. The officially recognized 135 ethnic groups are eligible for citizenship, and they include the main ethnic groups—Baman, Rakhine, Chin, Shan, Karen, Mon and Karenni. Chapter II, Article 3, of the Citizenship Act states that only these groups and others that settled in Burma before 1823 are entitled to Burmese citizenship. It is often difficult to prove that one had settled in Myanmar before 1823, and even if one manages to prove that, the immigration officer will often reject the evidence when he discovers you are a Muslim.

There are processes in the 1982 Citizenship Act for acquiring naturalized citizenship, but this citizenship is not the same as naturalized citizenship in most other countries. In Myanmar, naturalized citizenship does not give the same rights as full citizenship; moreover, it is not even an intermediary stage in the path to full citizenship. Naturalized citizens do not enjoy equal professional opportunities, and they cannot stand for elected office. Further, under Burmese law, naturalized citizenship can be revoked for a number of reasons such as “showing disaffection or disloyalty to the State” and “committing an offence involving moral turpitude”.

It is clear that the future of Myanmar and its whole reform process cannot be assured unless the question of citizenship for the Burmese Muslims is properly addressed. The international community must push the Myanmar government to amend its 1982 Citizenship Act to ensure that all qualified persons in the country have equal access to the right to citizenship and are not discriminated against on the grounds of ethnicity and religion.

References

Accessed: 04 February 2014

http://www.theweek.co.uk/asia-pacific/burma/47364/burma-regime-inciting-rakhine-conflict-discredit-aung-san-suu-kyi

http://observers.france24.com/content/20130424-muslim-burmese-refugees-camps-fear

http://www.dvb.no/news/reports-of-state-involvement-in-burma-unrest-un-expert/27315

http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2013/04/969-the-strange-numerological-basis-for-burmas-religious-violence/274816/

http://www.patheos.com/blogs/dannyfisher/2013/06/this-is-time-magazines-cover-in-every-country-in-the-world-this-week-except-the-united-states/

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/25/opinion/will-hatred-kill-the-dream-of-a-peaceful-democratic-myanmar.html?ref=opinion

President, Federation of Workers’ Union of the Burmese Citizens (in Japan).