Contents *Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited

SPF China Observer

HOMENo.62 2025/07/09

China's Rare Earth Export Restrictions and Other Countries' Responses: Strategies for the Main Battleground of Economic Security

Yuki Kobayashi (Senior Research Fellow, Sasakawa Peace Foundation)

1. China Tightens Rare-Earth Export Controls

In April 2025, China implemented export restrictions on seven rare earths as a response to tariffs imposed by the U.S. Trump administration, and the impact of these restrictions is spreading around the world. Due to the stagnation in the supply of parts using rare earths, not only have U.S. manufacturers been forced to suspend production of automobiles, but automakers in Europe and Japan have also suspended production.[1]

As discussed in detail below, rare earths, for which China has implemented export controls, are used in data equipment, motors and turbines for electric power vehicles (EVs) and wind power generation and are essential for both digital transformation (DX) and green transformation (GX), which have become international trends in the 21st century. It also includes rare earths essential to the aerospace industry and laser manufacturing, and the impact could extend to military equipment. Rare earths cannot be utilized as-is as a resource but can only be used through complex refining techniques. China dominates the international market for both mining and refining. Considering these circumstances, it can be said that this measure is the main battleground of economic security for the countries, and they are forced to take countermeasures.

The concept of economic security is known to have emerged in the early 20th century, but it has only rapidly spread to the international community since the 2010s, to summarize the proposed definition,

- (i) To protect the people from threats such as supply disruptions of critical commodities and advanced technologies and excessive dependence on other countries, and to maintain their survival and the sovereignty of the nation.

- (ii) Use of critical commodities or advanced technology to expand its own interests or achieve diplomatic objectives.

Thus, there are two aspects of “defense” and “offense”. It is also a concept that encompasses energy security and food security by adding the presence of technologies as well as the production and supply of resources and food.[2] According to the above definition, the current situation in the world is that China, using its abundant rare earth reserves and refining technology as a shield, is on the “offensive” to expand its own influence, while other countries are forced to play “defense”.

This paper will first identify the characteristics of the seven rare earth elements for which China has implemented export controls, then analyze China's measures and the responses of other countries from the perspective of economic security. Finally consider the measures that should be taken by each country, including Japan.

2. Seven Rare Earth Elements and China's Export Controls

(1) Types of rare earths for which export controls have been tightened

Rare earths refer to 17 elements that have electrical and chemical properties such as permanent magnets, of which seven are light rare earth elements and 10 are heavy rare earth elements. All of these are indispensable for high-tech industries, but heavy rare earths are indispensable and more important in fields directly related to national security, such as laser equipment and the aerospace industry.[3] The seven elements for which China has tightened export controls are all heavy rare earths, and their main uses are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Rare Earths for which China has tightened export controls

| Name | Main applications |

|---|---|

| Samarium | Sensors, Medical Devices, Automotive Parts |

| Gadolinium | Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents, nuclear reactor control rods |

| Terbium | Anti-counterfeiting fluorescent printing, laser processing |

| Dysprosium | EVs, hybrid vehicle motors, wind turbines, data storage devices |

| Lutetium | Laser, Radiation Therapy |

| Scandium | Electrode Materials, Lasers, Aircraft Parts |

Source: Prepared by the author based on Katsuhiro Saito, "Rare Metals; Rare Earths The Amazing Abilities," (in Japanese) C&R Research Institute, May 2019, etc.

On 4 April 2025, China's Ministry of Commerce announced the strengthening of export controls on rare earths in Table 1 in accordance with the country's Export Control Law and Regulations on Export Control of Dual-Use Items to ensure national security and fulfill international obligations to prevent the proliferation of nuclear weapons and other military equipment. When a business exports these items, it is required to apply for a permit from the Ministry of Commerce in accordance with the above laws and ordinances. If there is any doubt about the application, customs clearance will not be allowed.[4] In effect, it appears to be retaliation for the U.S. tariffs.

Although China's measures are not export volume restrictions, customs clearance delays have affected supply volumes and transaction prices. According to Argus Media, a British research firm that analyzes global trends in rare earths, the trading price of dysprosium in Europe as of May 1 tripled to $850 per kilogram, three times higher than in early April, and terbium tripled to $3,000 before the regulation. This is the largest monthly increase since May 2015, when data can be traced back. As a result, economic activities in other countries have been affected, as we have seen earlier.

(2) China's capabilities in rare earth mining and refining

These export restrictions are based on China's overwhelming dominance in the international market for rare earth mining and refining.

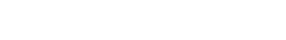

According to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), a U.S. government agency, 48.9% of the world's rare earth reserves are unevenly distributed in China, which also accounts for 68% of the total mined by country (see Figure 1). Since the 2010s, when the importance of economic security has become strongly recognized, diversification of mining countries has been observed in the world, such as the resumption of the closed Mountain Pass mine in the United States, but the disproportionate reserves of heavy rare earths, which are indispensable for security-related equipment, are in China, which is the source of market dominance. More than 90% of the reserves of rare earths at the Mountain Pass Mine and mines in Australia are light rare earths, while the Xinfeng Mine in China's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region accounts for 40% of the heavy rare earths.[5] It is not easy to secure alternative suppliers.

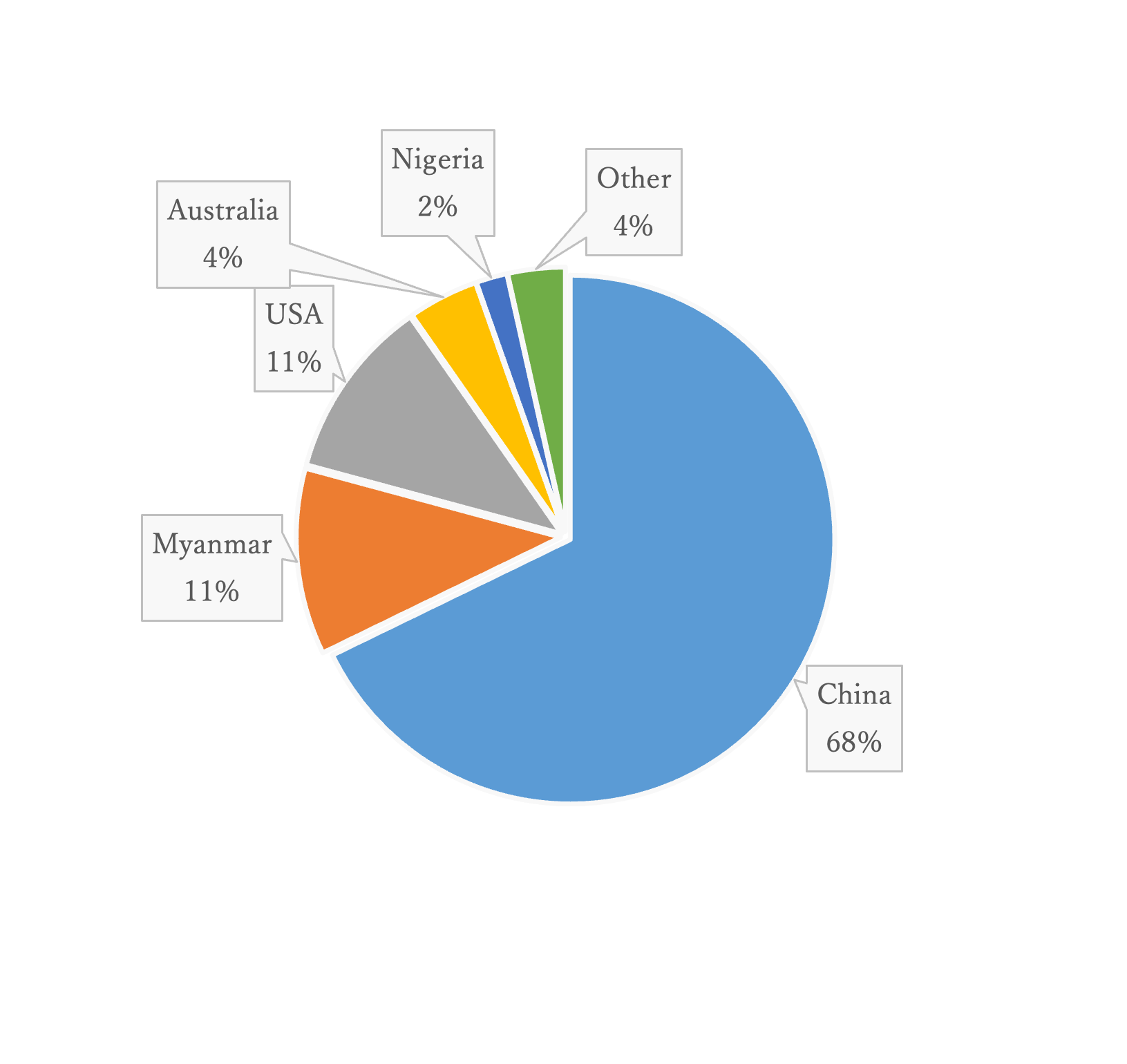

When it comes to the refining sector, China's market dominance is even more pronounced, accounting for over 90% (see Figure 2). The world must rely on Chinese refining to utilize rare earths for the applications shown in Table 1.

Figure 1:Mining Ratio of Rare Earths by Country (2023)

Figure 2:Rare Earth Refining Ratio by Country

One of the reasons why the supply of rare earths has been concentrated in China is that a large amount of pollutants such as toxic gases, sludge, and radioactive materials are generated in the process from mining and refining, and the physical burden on workers and the surrounding environment is tremendous. The reason is that to separate rare earths mixed in a single ore requires the use of a large number of chemicals.[6] In France, which until the 1980s led the international market for rare earths along with the United States, wastewater from a plant in the western part of the country engaged in the refining of rare earths and minerals was reported to contain radioactive materials at concentrations nearly 100 times higher than the average for other regions.[7] As a result, environmental protection momentum in Western countries increased, and most operators withdrew from mining and refining of rare earths or drastically reduced the scale of their operations, while the initiative shifted to China, where environmental regulations are looser than in other countries. Since the 1950s, China has focused on rare earths as an indispensable resource for the next generation, and in 1992, Deng Xiaoping, the country's supreme leader at the time, said, “There is oil in the Middle East and rare earths in China”.[8] As discussed below, China has also postponed the resolution of labor condition improvements and environmental pollution that could not be resolved in Western countries, but it has thus established a monopoly on rare earth supply and is in a position to exert influence over the world's advanced technology and military industries.

3. Response by other countries

(1) Western democracies are rebuilding supply chains

This tightening of export controls has accelerated the rebuilding of rare-earth supply chains in Western democracies, where the risk of dependence on China has become apparent.

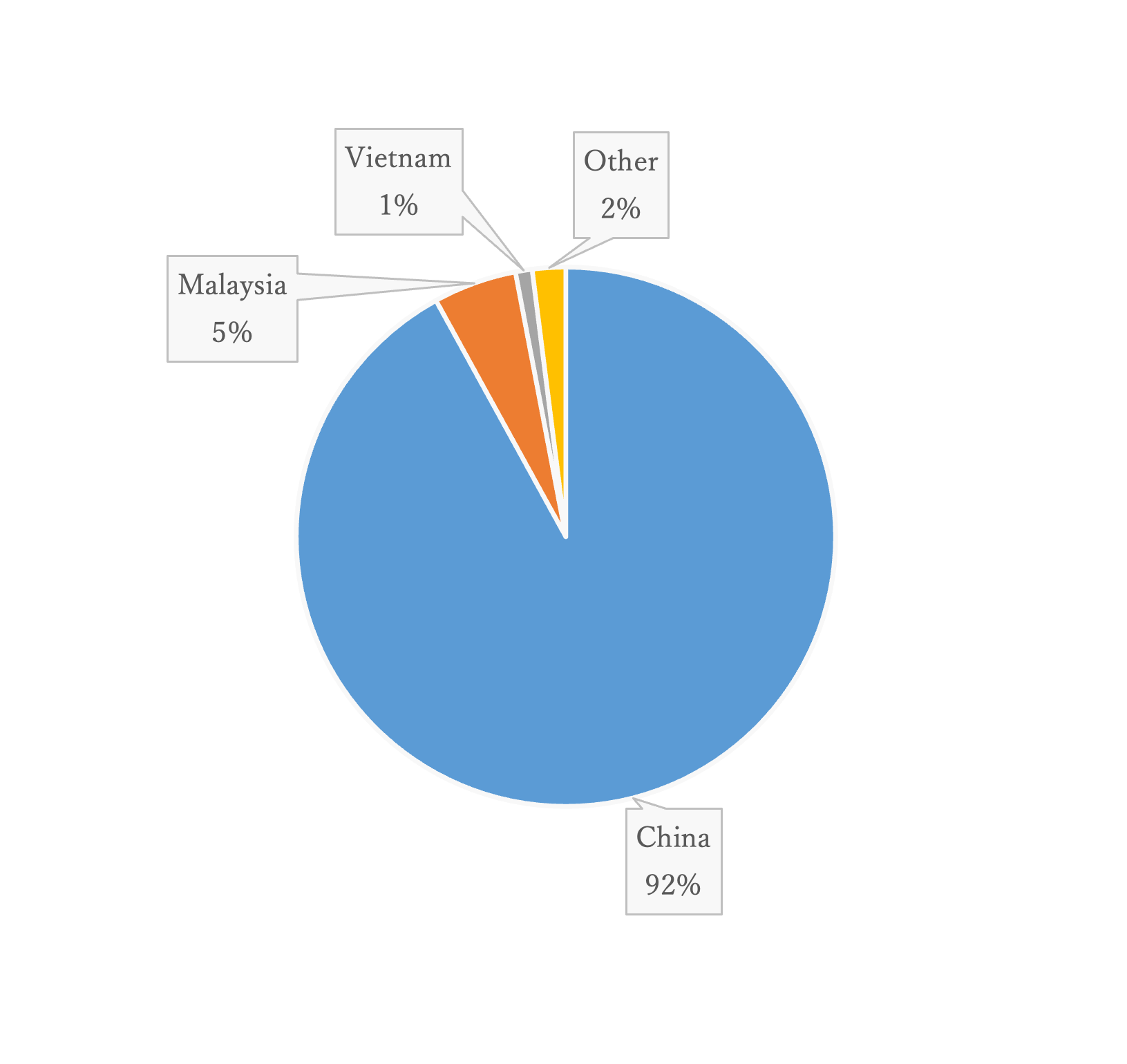

In particular, the United States is experiencing a growing sense of crisis. In March 2025, prior to China's export controls, President Trump signed an executive order called “Immediate Measures to Increase American Mineral Production” and announced an increase in rare earth production.[9] The following April, the U.S signed a “Mineral resources agreement” with Ukraine, which is facing a military invasion by Russia, in return for military assistance.[10] According to Ukrainian government data, the distribution and types of rare minerals in the country are shown in Figure 3 and Table 2.

Figure 3:Major Mineral Reserves in Ukraine

Table 2: Major mineral resources (including rare earths) produced in Ukraine and their uses

| Name | Application |

|---|---|

| Beryllium | Aircraft, rockets, and missile components |

| Graphite | Materials for large-scale lithium-ion batteries for EVs |

| Lithium | Main raw materials for lithium-ion batteries (smartphones, PCs, EVs, etc.) |

| Titanium | Satellite Components |

| Non ferrous metal | Semiconductors, electronic components |

| polymetallic | Lithium-ion battery components |

| Rare Earths | Lithium-ion battery components |

| Iron | Steel Products |

| Manganese | Lithium-ion battery |

| Uranium | Nuclear power generation |

Source: Prepared by the author based on Gullaume Pitron “La Guerre des metaux rares” (Japanese version), Hara shobo, March 2020, etc.

At present, it has been confirmed that Ukraine has reserves of critical minerals used in the EVs, aerospace and nuclear industries, but it is unclear how much of the heavy rare earths that China has imposed export restrictions on are reserved.[11] Moreover, the issue of refining is not solved by this agreement. As Figures 1 and 2 clearly show, although the U.S. mines rare earths, it exports almost all of them to China for refining. The situation of high tariffs with China is not only strangling itself, but if the United States does not promote in-house production of refining, it will continue to be dependent on China forever.

To this end, the government is seeking to expand its mining and refining operations to the few remaining rare earth operators in the U.S., as well as to attract refiners from allied and like-minded countries to the U.S.

MP Materials, which is engaged in rare earth mining at its Mountain Pass mine in California, has announced that it will expand its mining and refining operations because the mine also contains rare earths that China has restricted for export.[12] In addition, Australia's Lynas, which is engaged in refining at its plant in Malaysia and occupies a certain position in the international market for rare earth refining, although it is far from China (see Figure 2), is building a new rare earth refining plant in Texas. From the perspective of national security, the U.S. Department of Defense is subsidizing the construction of the plant by 258 million dollars (about 36.8 billion yen) as part of restructuring the rare earth supply chain. The plant is scheduled to start operations in 2026.[13]

(2) Movements in Japan

Japan was the first country in the world to experience Chinese restrictions on rare earth exports. In September 2010, the Japan Coast Guard demanded that a Chinese fishing boat operating in Japanese territorial waters off the Senkaku Islands leave the area, but it did not comply. The captain of the fishing boat was arrested on suspicion of obstruction of justice after the fishing boat struck a Coast Guard patrol boat. China reacted and imposed restrictions on exports of rare earths to Japan. According to trade statistics from the Ministry of Finance, imports of rare earths from China plummeted from 2,246 tons in September 2010 to 1,278 tons in October.[14]

Based on this background, Japan has been promoting measures from two aspects. The first is the establishment of a rare earth supply chain outside of China. Sojitz, a general trading company, and the Japan Energy, Metals & Minerals Corporation (JOGMEC) invested in the aforementioned Lynas in 2011, and in March 2023, they will provide an additional loan of approximately 18 billion yen to supply up to 65% of the heavy rare earths (dysprosium and terbium; see Table 1) mined by Lynas and refined at its plant in Malaysia to Japan.[15] This is Japan's first acquisition of rare earth interests. In May 2024, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) decided to contribute 100 million euros (about 16.5 billion yen) to rare earth refining by Caremag of France through JOGMEC. In March 2025, energy companies Iwatani & Co., Ltd. and JOGMEC decided to invest up to 110 million euros in the company and participate in rare earth refining. The supply of dysprosium and terbium (see Table 1), which are heavy rare earths, is expected to be equivalent to 20% of the demand in Japan in the future.[16]

The second is efforts to reduce dependence on rare earths themselves. The New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO) has started developing motors that do not use rare earths from 2024,[17] and parts manufacturers and start-ups are competing to develop rare earth-free motors with the aim of mass production between 2027 and 2028. First, it is expected to be put to practical use in small EVs.

4. Outlook: Will China's Dominance of Rare Earths Continue?

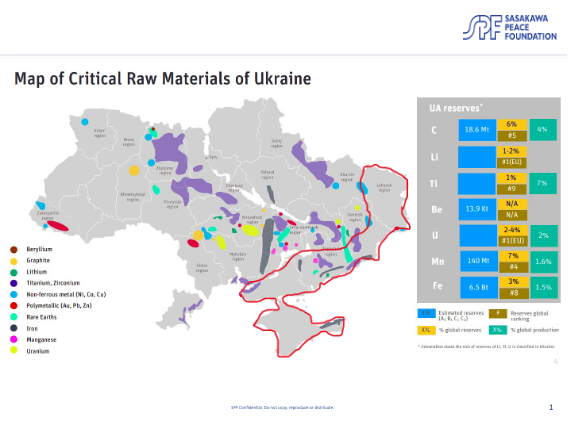

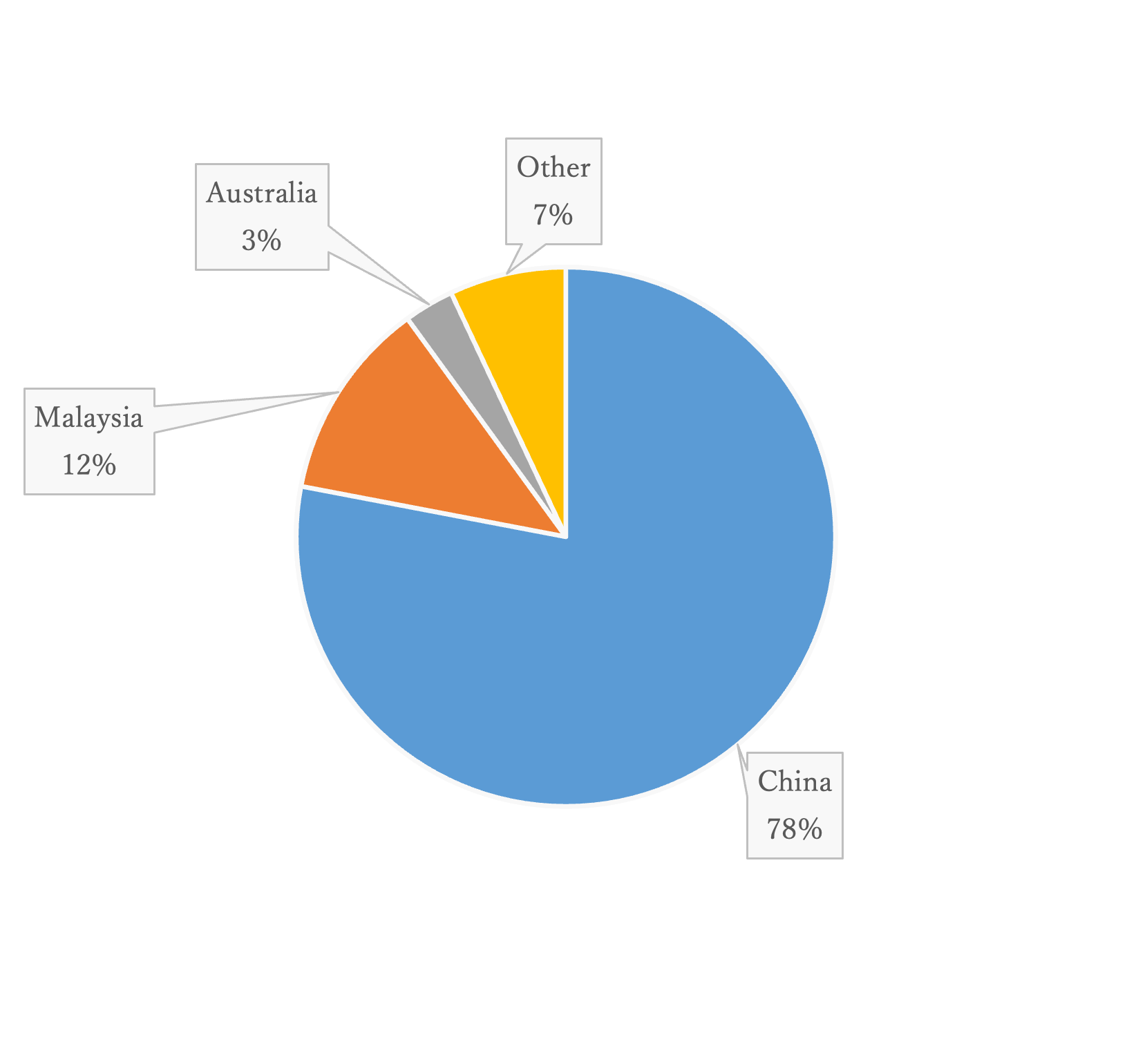

To what extent will “Western democracies” efforts to reduce their dependence on China be successful? The IEA estimates the refining ratio by country for the rare earth situation in 2040 as follows (see Figure 4).

Figure 4:Rare-earth Refining Ratio by Country as of 2040

Although this will be down from 92% in 2023, China will still account for 78% of rare earth refining in 2040 and will continue to have a near monopoly. The fact that Malaysia is mainly a refinery operated by Lynas of Australia, which receives investment from Japan, and that the total of the two countries, Malaysia and Australia, is expected to reach 15%, can be seen as a sign that Japan's establishment of supply chain out of China ahead of the United States and other countries will bear fruit to some extent.

China's figure of 78% could fall further for three reasons. First, this figure is a forecast as of 2023 and does not fully reflect the acceleration of the exit from China following China's restrictions on rare earth exports. Second, a change in awareness has been observed in China, where environmental regulations were previously looser than in other countries and awareness of environmental protection was not high. Since the 2010s, there has been an increase in the number of cases in which local or foreign medias have reported on the reality of environmental pollution, such as dilute sulfuric acid and hydrochloric acid generated by refining in Jiangxi Province, where rare earth mines are located.[18]

Third, with the progress of DX and GX, the demand for rare earths will continue to increase, and it will not only be difficult for China alone to cover the increase, but it has also been pointed out that by 2030, China itself may not be able to supply itself in the amount of rare earths required, apart from refining[19], and it is highly likely that it will be necessary to increase mining and refining outside of China. According to the IEA's estimates, the total global demand for rare earths in 2023 will reach 93 kilotons (1 kiloton equals 1,000 tons) to 134 kilotons in 2030 and 169 kilotons in 2040. The breakdown shows that non-energy applications are expected to increase by 36% compared to 2023, and renewable energy applications are expected to increase more than fourfold compared to the same year, assuming the realization of decarbonization. If China becomes unable to supply itself in rare earths around 2030, it will need to mine 35 kilotons outside China for the 10-year increase required until 2040.In fact, the presence of mines in Africa is attracting attention, but the IEA has included a section on “Risk Management Associated with the Transition to Cree Energy” in its “Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024” to ensure that mine development does not impose sacrifices on the environment and residents of the region, given the large environmental impact of mining and refining of rare earths and minerals. It calls for the importance of sustainability in cooperation with other countries.[20]

5. Conclusion: Establishing Economic Security and the Role of Japan

We have analyzed the impact of China's export restrictions on rare earths from the perspective of economic security, using various data. Based on the results, I would like to emphasize the following two points that each country, including Japan, should address in the future.

First, we should continue our efforts to build supply chain out of China and establish them as soon as possible. Based on the IEA's projections for 2040, this is essential. If the expansion of rare earth refining in the United States and France, which do not seem to be reflected in the forecast, proceeds as planned, and a supply system among like-minded countries is established, mainly light rare earths, which are abundant reserves in Western democracies, and heavy rare earths can be supplied to a certain extent, they can expect to strengthen China's ability to resist aggression in terms of economic security.

Second, once the supply chain has been established and the Western democracies have overcome their economic security weaknesses to some extent in the manner described above, they should seek cooperation with China. As we saw in Section 2, the mining and refining of rare minerals such as rare earths has a large impact on the environment. The United States and France, which were advanced countries in rare earth refining, and China, which subsequently established a monopoly system, and Japan, which has relied on imports from them, are in a position to be well aware of the seriousness of environmental pollution associated with rare earth production. Without waiting for the IEA to point out, it is not desirable to ensure the progress of DX and GX in a way that transfers pollution to new regions, such as Africa, where there are many untapped mines. How can we reduce the burden on the environment and preserve the livelihoods of local residents, and to what extent can we tolerate the rise in the price of rare earth products as a result, and establish sustainable rare earth production? These are global issues, and it is essential for each country to pool its wisdom and explore solutions.

Japan is in a position to make effective use of its advanced technological capabilities. The development of motors that do not depend on rare earths will lead to a reduction in dependence on rare earths worldwide, and technologies to reduce environmental impact can be utilized in mines where rare earths are mined and refined, including in China. When China imposed restrictions on rare earth exports in 2010, it stated that the ostensible reason was to prevent environmental destruction as well as the possibility of resource depletion, and Japan also had a history of cooperation in environmental protection as one of the proposals.[21] Thus, in terms of the definition of economic security mentioned at the beginning, Japan has the potential to utilize its technological capabilities to expand its national interests. In the future, when China's dominance of rare earths is relatively declining, it is necessary to start thinking about how to utilize its technological capabilities for international contributions.

1 For more information on the European situation, see the European Association of Automotive Supplier (CLEPA) website “Urgent action needed as China's export restrictions on rare earths disrupt European automotive supply chains” 4 June 2025. [https://www.clepa.eu/insights-updates/press-releases/urgent-action-needed-as-chinas-export-restrictions-on-rare-earths-disrupt-european-automotive-supply-chains/c]

For Japan, please refer to Suzuki's website and news release “Suspension of production of some models produced in Japan” on May 30, 2025. [https://www.suzuki.co.jp/release/d/2025/0530/]

2 For the definition and conceptual arrangement of economic security, see Kazuhiro Nakatani, “Economic Security and International Law” (in Japanese) Shinzansha, July 2024, pp. 3-9.

3 Katsuhiro Saito, “Rare Metals; Rare Earths-The Amazing Abilities” (in Japanese) C&R Research Institute, May 2019, pp. 120-127.

4 Ministry of Commerce of the People's Republic of China “Announcement of the Ministry of Commerce and the General Administration of Customs [2025] No. 18 Announcing the Decision on the Implementation of Export Control on Certain Medium and Heavy Rare Earth Related Items” (in Chinese) April 4, 2025. [https://www.mofcom.gov.cn/zwgk/zcfb/art/2025/art_9c2108ccaf754f22a34abab2fedaa944.html]

5 JOGMEC, “Rare Earth Supply and Challenges” (in Japanese), June 27, 2024. [https://mric.jogmec.go.jp/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/mrseminar2024_01_02.pdf]

6 Katsuhiro Saito, “Rare Metals; Rare Earths-The Amazing Abilities” (in Japanese) pp. 128-131.

7 Gullaume Pitron “La Guerre des metaux rares” (Japanese version), Hara shobo, March 2020, pp. 71-76.

8 Yoshikiyo Shimamine, Economic Research Department, Dai-ichi Life Research Institute, “Rare Earths as a Compensation for the Tariff War Against China 1 ~ Is the United States Prepared to Abandon China's Monopoly of Rare Earths ~” (in Japanese) April 10, 2025. [https://www.dlri.co.jp/report/macro/431667.html]

9 WHITE HOUSE website “Immediate Measures to Increase American Mineral Production” 20 March 2025. [https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/03/immediate-measures-to-increase-american-mineral-production/]

10 Forbes website “The Only U.S. Rare Earth Mine May Win Big From Trump’s China Tariffs” 21 April 2025. [https://www.forbes.com/sites/alanohnsman/2025/04/21/the-only-us-rare-earth-mine-may-win-big-from-trumps-china-tariffs/]

11 For more information on Ukraine's mineral resources, see my article “The End of the War in Ukraine and the Speculations of the Great Powers on Natural Resources” (in Japanese), March 20, 2025. [https://www.spf.org/jpus-insights/uspolicy-community/spf-amuspolicy-community-documents-05.html]

12 WHITE HOUSE website “Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Secures Agreement to Establish United States-Ukraine Reconstruction Investment Fund” 1 May 2025. [https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/05/fact-sheet-president-donald-j-trump-secures-agreement-to-establish-united-states-ukraine-reconstruction-investment-fund/]

13 Lynas website “U.S. DoD Strengthens Support for Lynas U.S. Facility” 1 August 2023. [https://wcsecure.weblink.com.au/pdf/LYC/02692868.pdf]

14 Institute of Social Science, The University of Tokyo, Tomoo Marukawa, “The Rare Earth Crisis in 2010” (in Japanese), June 23, 2016. [https://web.iss.u-tokyo.ac.jp/crisis/essay/2010-2010979192-924201042010-wto201092219412010-nhk924924-120109220310180922461012781200920112102010.html]

15 METI website “We will acquire the first interest in rare earths in Japan” (in Japanese), 7 March 2023. [https://www.meti.go.jp/press/2022/03/20230307001/20230307001.html]

16 METI website “The governments of Japan and France are collaborating to support heavy rare earth projects in the French Republic” (in Japanese), 17 March 2025. [https://www.meti.go.jp/press/2024/03/20250317001/20250317001.html]

17 NEDO website “Economic Security Critical Technology Development Program begins development of heavy rare earth-free magnets and rare earth-free magnets, as well as the design and development of motors suitable for next-generation magnets” (in Japanese), 25 July 2024. [https://www.nedo.go.jp/news/press/AA5_101765.html]

18 Gullaume Pitron “La Guerre des metaux rares” pp. 29-31.

19 Katsuhiro Saito, “Rare Metals; Rare Earths-The Amazing Abilities” pp. 169-170.

20 IEA “Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024”pp. 202-223. [https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/ee01701d-1d5c-4ba8-9df6-abeeac9de99a/GlobalCriticalMineralsOutlook2024.pdf]

21 Tomoo Marukawa, “The Rare Earth Crisis in 2010”.