Contents *Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited

SPF China Observer

HOMENo.57 2024/10/11

Can the China-Russia Nuclear Energy Agreement Put the Brakes on Beijing’s Nuclear Weapons Buildup?

Yuki Kobayashi (Research Fellow, Sasakawa Peace Foundation)

1. Concern over China’s Fast Breeder Reactor (FBR)

Nuclear non-proliferation experts are voicing concern that China’s fast breeder reactor (FBR), which has been constructed on the coast of Fujian Province and appears to have gone into test operation, may be a step toward building up nuclear arms capabilities. This is because the FBR may be used to reprocess spent nuclear fuel to extract copious quantities of ultrapure plutonium-239, the type of plutonium best suited for the production of nuclear weapons.

Regarding the FBR in China, Russia has been providing technical assistance including the supply of nuclear fuel. The two countries signed a cooperation agreement on FBRs back in 2018. Another agreement, which includes some new commitments, was concluded at the China-Russia summit meeting in March 2023.[1] When a country transfers its nuclear technology for facilities that may lead to nuclear proliferation, such as FBRs, its agreement with the recipient country usually includes a provision prohibiting diversion for military use. That is why I pointed to the importance of analyzing the nuclear energy agreement between China and Russia in my previous article, “Intention behind Russia’s Involvement in China’s Plutonium Production.”

The Sasakawa Peace Foundation obtained a copy of the Russian text of the China-Russia Nuclear Energy Agreement of 2018. After translating it into English, we analyzed its content together with nuclear non-proliferation experts from Japan and abroad, including a Russian national. As a result, we found that the agreement includes provisions prohibiting China from using the nuclear fuel and technology provided by Russia for any military purposes, including, but not limited to the production of nuclear weapons and nuclear bombs. Some experts point out that if the agreement is complied with, it would be difficult for China—given the amount of plutonium currently held—to field a stockpile of roughly 1,500 nuclear warheads by 2035 as projected by the U.S. Department of Defense,[2] or it would take much more time to achieve that end. At the same time, however, the agreement has no mention of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspections of nuclear facilities and materials, meaning that the international community has no way of checking whether China actually complies with the agreement.

This article first provides an overview of the FBR, which China is working to bring into full operation, and estimates the country’s nuclear weapon production capability by reference to the amount of plutonium held in China. Then, it examines the China-Russia Nuclear Energy Agreement to analyze its impact on China’s nuclear armament.

2. Basic Structure of an FBR and Development Status in China

(1) How an FBR works

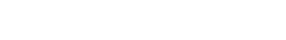

An FBR consists of two fuel regions: the core fuel region that releases thermal energy and neutrons through nuclear fission and the blanket fuel region composed of non-fissile uranium-238, which “blankets” the core fuel (see the Figure).

Figure:FBR Fuel Composition (Core Fuel Shown in Pink, Blanket Fuel in Blue)

Core fuel burns, and the generated thermal energy is used to generate electricity. At the same time, uranium-238 constituting blanket fuel absorbs neutrons that have been released and thus changes into plutonium-239, meaning that plutonium is newly produced within the reactor. High-purity plutonium-239, considered best-suited for use in nuclear weapons, can be obtained by reprocessing this blanket fuel.

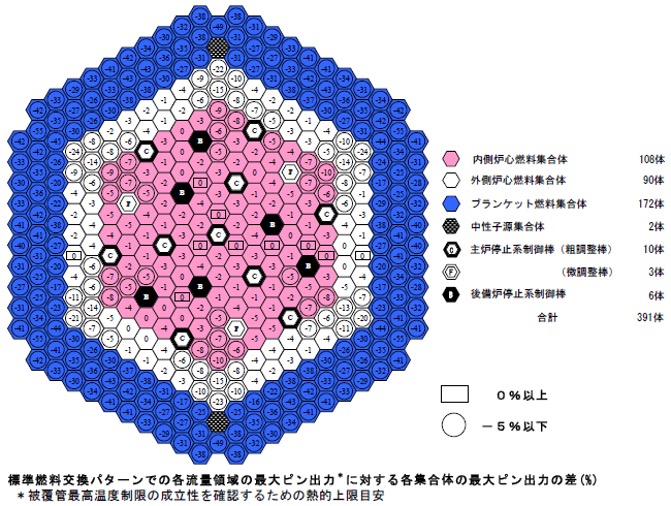

In accordance with its agreement with China, Russia delivered core fuel to China at the end of 2022.[3] If China successfully brings its FBR, a medium-sized reactor with an output of 600 MWe, into operation along with the fuel reprocessing plant, it can extract weapon-grade plutonium-239 by the 100 kilograms per year. Satellite images of the FBR captured in July 2023 and thereafter consistently show a white stream extending from the drainage outlet. This means that a massive amount of seawater is being circulated through a nuclear reactor to remove heat and then discharged into the sea, indicating that the reactor has been put into pilot operation (see the Satellite Image).

Satellite Image:A Gush of Water Flowing out of the Drainage Outlet of CFR600

According to the latest data (April 2024) from the International Panel on Fissile Materials (IPFM), an independent group of experts doing research on trends in fissile material stockpiles around the world, China is believed to hold nearly three metric tons of plutonium available for weapons (see the Table). In contrast to other countries, most of the plutonium currently held in China is believed to be for military purposes as its reprocessing plant, which is designed to reprocess spent fuel from civilian nuclear power reactors for plutonium extraction, has yet to go into operation.[4]

Table:Stocks of Plutonium by Country

| Country | Total plutonium (Pu) (tons) |

Of this, Pu available for weapons (tons) |

|---|---|---|

| Russia | 193 | 88 |

| United States | 87.6 | 38.4 |

| United Kingdom | 119.6 | 3.2 |

| France | 98 | 6 |

| China | 3 | 2.9 |

| Pakistan | 0.54 | 0.54 |

| India | 10 | 0.7 |

| Israel | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| North Korea | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Japan | 45.1 | 0 |

Source:International Panel on Fissile Materials

Plutonium needed to produce one nuclear weapon is estimated to be 3.5 ± 0.5 kilograms for calculation. This means that if China used its whole stock of plutonium, it would produce 725 to 965 nuclear warheads. This, together with the existing inventory of warheads estimated at 500, would bring the total number up to 1,225 to 1,465.[5] These figures are almost equal to the maximum nuclear warheads (1,550) that the United States and Russia are allowed to deploy as stipulated in the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) signed between the two nuclear powers. However, for any country managing its nuclear weapons and materials based on criteria comparable to those in the United States, it would be unrealistic to deploy all warheads available. The United States and Russia each have more than 3,000 non-operational warheads. If China’s strategic vision is to deploy as many warheads as the United States, it would be imperative for the country to increase the production of plutonium and build up its inventory of non-operational nuclear weapons. That is why much attention is being paid to the FBR in Fujian Province and the operation status of the reprocessing plant.

3. Analysis of the China-Russia Nuclear Energy Agreement of 2018

The China-Russia Nuclear Energy Agreement on Chinese FBRs was concluded in June 2018.

Article 5 of the agreement provides that Russia shall provide technical assistance to China with the development of FBRs, including the supply of core fuel, while Article 7 stipulates that any disputes over the performance or interpretation of the agreement shall be referred to the International Court of Arbitration as a third-party arbitrator. The most important provision from the viewpoint of nuclear non-proliferation is Article 8, paragraph 2. An English translation of the provision reads as follows:

“2. Nuclear materials, equipment, special non-nuclear materials and related technologies received by the People's Republic of China in accordance with this Agreement, as well as nuclear and special non-nuclear materials, facilities and equipment produced on their basis or as a result of their use:

Shall not be used to produce nuclear weapons and other nuclear explosive devices or to achieve any military purpose;”

It clearly states that the technology provided by Russia and any items derived therefrom may not be used for any military purposes, including, but not limited to the production of nuclear weapons and nuclear bombs. Pavel Podvig, senior researcher at the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR) gives positive acknowledgement, noting that the terms of the agreement clearly prohibit China from using the plutonium obtained with use of the fuel or technology provided by Russia for any military purposes.[6] Meanwhile, Tatsujiro Suzuki, professor at Nagasaki University Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (RECNA), points to the need for China to accept IAEA safeguards, i.e., monitoring and inspection of nuclear facilities and materials, which he says would help “dispel concerns over the possibility of using them for military purposes.”[7] China is one of the countries specifically allowed to possess nuclear weapons under the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) and not required to accept IAEA safeguards. However, in the past when transferring its uranium enrichment technology, which also poses the possibility of diversion for military use, Russia demanded China to accept IAEA safeguards and China agreed. This means that the IAEA provides assurance that China’s enrichment plant, built with the help of Russia, does not produce uranium fuel with density exceeding the prescribed limit. Tomonori Iwamoto, Secretary General of the Institute of Nuclear Materials Management (INMM) Japan Chapter, takes a cautious look at Russia’s latest technology transfer to China, saying, “This time around, Russia did not demand China to accept IAEA safeguards, which seems to me a step backward from its commitment to nuclear non-proliferation.”[8]

4. Enhancing Transparency in the Transfer of Nuclear Materials and Nuclear Energy Technology: Japan’s Role

The fact that the China-Russia Nuclear Energy Agreement contains a provision prohibiting the diversion for military purposes of the plutonium produced by the FBR deserves a degree of credit from the viewpoint of nuclear non-proliferation. However, China has so far disclosed no information on the operational status of the FBR or any other developments at the facility for scrutiny by the international community, other than simply claiming that it is for civilian use. Also, there is no ruling out the possibility of such transfer of nuclear materials or nuclear energy technology leading to “vertical proliferation,” i.e., a significant boost to a country’s nuclear weapon capability, even when both sides already possess nuclear weapons. In order to prevent nuclear proliferation, it is imperative to enhance transparency in the transfer of nuclear materials and nuclear energy technology regardless of whether or not countries involved are in possession of nuclear weapons.

Having obtained greenlight for commencing operation of its reprocessing plant in Rokkasho, Aomori Prefecture, under the revised Japan-US Nuclear Cooperation Agreement of 1988, Japan, together with the IAEA and the United States, developed safeguards system for large-scale reprocessing facilities. Taking advantage of its unique experience as the only non-nuclear weapon state involved in such effort, Japan should raise questions about the current state of affairs where the NPT-recognized nuclear weapon states are not required to accept IAEA inspections and play a leading role in international discussions for enhancing nuclear non-proliferation. This will also contribute to improving the security environment for Japan, a country that would be directly affected by nuclear weapons buildup in China.

1 “China and Russia sign fast-neutron reactors cooperation agreement” March/22/2023 [https://www.world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/China-and-Russia-to-cooperate-on-fast-neutron-reac]

2 Office of the Secretary of Defense, “MILITARY AND SECURITY DEVELOPMENTS INVOLVING THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA 2022” [https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/23321290/2022-military-and-security-developments-involving-the-peoples-republic-of-china.pdf]

3 Rosatom, “ROSATOM ships fuel for China’s CFR-600 fast reactor launch” December 28 2022 [https://rosatom.ru/en/press-centre/news/rosatom-ships-fuel-for-china-s-cfr-600-fast-reactor-launch/]

4 IPFM[Countries: China] 13 April 2024.

5 The numbers of warheads are from the Stockholm Institute for Peach Research (SIPRI), “SIPRI YEARBOOK 2023.” [https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/YB23%2007%20WNF.pdf]

6 International Panel on Fissile Materials (IPFM) BLOG, “Russian laws prohibit military use of HEU supplied to China,” May 15, 2024.

7 Responses via email to the author’s inquiries. July 23, 2024.

8 Responses in an interview conducted by the author. July 23, 2024.