Satellite Imagery Analysis 2024/05/30

Intention behind Russia’s Involvement in China’s Plutonium Production

Yuki Kobayashi (Research Fellow, Sasakawa Peace Foundation)

1. Latest Developments in China’s Construction of Fast Breeder Reactors

China has been working on the construction of a fast breeder reactor (FBR) on the coast of Fujian Province, drawing attention from experts on nuclear non-proliferation and nuclear arms control. This is because the FBR may be used to reprocess spent nuclear fuel to extract copious quantities of ultrapure plutonium-239, the type of plutonium best suited for the production of nuclear weapons. It has been pointed out that the plant may serve as a hub of China’s plutonium supply as the country seeks to expand its nuclear arsenal with the aim of establishing military capability equal to that of the United States. The U.S. Department of Defense also estimates in its published report that China’s operational nuclear warheads will double to be over 1,000 by 2030.[1] In December 2022, Russia delivered initial fuel to be loaded in the FBR in China, and in 2023, a sign of test operation of the reactor was observed (see my article "Water Drainage Observed at China’s Fast Breeder Reactor")

Full-Scale Operation Likely in Near Future. In March 2023, China and Russia had a summit meeting and signed a cooperation agreement pertaining to this FBR, which turned out to include provisions about the treatment of spent nuclear fuel.[2] The two countries have not disclosed the details of the agreement. Normally, an agreement for nuclear power generation that involves the use of an FBR places restrictions, such as that the fuel supplier country takes back spent fuel from the user country and/or requests that the user accept inspections of the nuclear reactor by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) so that fuel user will not reprocess spent fuel at its own discretion to produce nuclear weapons. If China cannot freely reprocess spent fuel from its FBR, that may affect its production of plutonium and of nuclear weapons in the future. This means that the country may have difficulty expanding its nuclear arsenal as the U.S. Department of Defense predicts.

This paper first estimates China’s nuclear arms production capability, referring to the overview of the FBRs that the country is working to put into full operation, as well as to China’s stockpile of plutonium. Then it discusses how Russia is trying to be involved in China’s plutonium production and nuclear armament.

2. Basic Structure of an FBR and Development Status in China

(1) How an FBR works

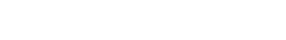

An FBR consists of two fuel regions: the core fuel region that releases thermal energy and neutrons through nuclear fission and the blanket fuel region composed of non-fissile uranium-238, which “blankets” the core fuel (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: FBR Fuel Composition (Core Fuel Shown in Pink, Blanket Fuel in Blue)

Core fuel burns, and the generated thermal energy is used to generate electricity. At the same time, uranium-238 constituting blanket fuel absorbs neutrons that have been released and thus changes into plutonium-239. This means that an FBR produces new plutonium and reprocesses spent fuel, thereby making more plutonium available than consumed for reuse to generate electricity, which is why FBRs have been called “dream nuclear reactors.” Japan, the United States, and France took the lead in technological development of FBRs for practical use, and Japan operated an FBR called Monju. However, due to the difficulty of managing liquid sodium as the reactor coolant, countries around the world except for Russia, China, and India have discontinued or frozen FBR development. It should also be noted that the plutonium extracted by reprocessing blanket fuel is high-purity plutonium-239, which is said to be the best plutonium for production of nuclear weapons. Any medium-sized or larger reactor in full operation would be able to reprocess spent fuel to provide copious quantities of plutonium by the 100 kilograms per year. Hence, an FBR and spent fuel reprocessing are also sensitive technologies in terms of nuclear non-proliferation.

(2) China’s plutonium stockpile and FBR development

The International Panel on Fissile Materials (IPFM) studies trends in stocks of nuclear materials around the world. In April 2024, the IPFM published the latest data on the stocks of plutonium by country (see Table 1).

Table 1: Stocks of Plutonium by Country

| Country | Total Plutonium (Pu) (tons) | Of this, Pu available for weapons (tons) |

|---|---|---|

| Russia | 193 | 88 |

| United States | 87.6 | 38.4 |

| United Kingdom | 119.6 | 3.2 |

| France | 98 | 6 |

| China | 3 | 2.9 |

| Pakistan | 0.54 | 0.54 |

| India | 10 | 0.7 |

| Israel | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| North Korea | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Japan | 45.1 | 0 |

Source: International Panel on Fissile Materials

Plutonium needed to produce one nuclear weapon is estimated at 3.5 kilograms, give or take 0.5 kilos, for calculation. This means that if China used its whole stock of plutonium, it would produce up to a little fewer than 1,500 nuclear warheads. This number is almost equal to the maximum nuclear warheads (1,550) that the United States and Russia are allowed to deploy as stipulated in the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) signed between the two nuclear powers. However, in light of nuclear arsenal operation and management, it is unrealistic to deploy all warheads these countries hold. The United States and Russia each have stockpiles of more than 3,000 non-operational nuclear warheads. If China had a strategic vision of deploying as many nuclear warheads as the United States, the country would need to do something about the present state, in which it holds less plutonium than the United Kingdom and France that have fewer nuclear warheads than China (the UK: 225, France: 290[3]) in order to produce more plutonium. It would also be essential that China increase its stockpile of non-operational nuclear arms. This is why the FBR in Fujian Province is attracting attention.

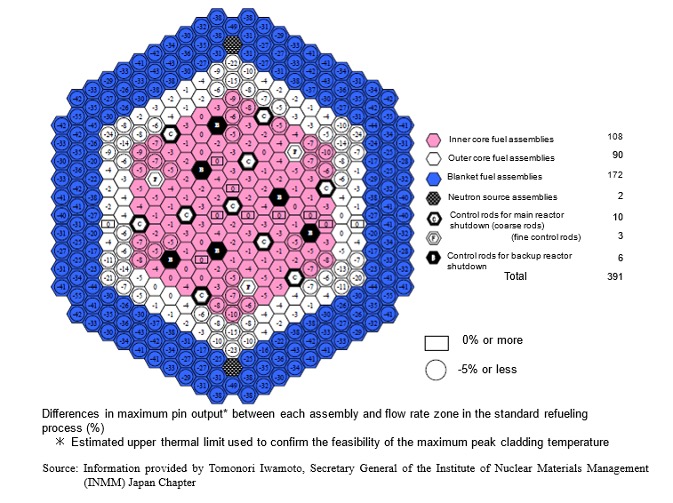

According to an IAEA report, in 2017, China began the construction of this FBR named CFR-600 (maximum output of 600 MW) in Fujian Province.[4] The report states “The first fuel loading will be launched at 2023,” and in late 2022, core fuel was delivered from Russia. Furthermore, in July 2023 and thereafter, a massive discharge of water into the sea was continuously observed, apparently after cooling the reactor. This indicates that CFR-600 came into test operation in that summer or thereafter (see Satellite Image 1).

Satellite Image 1: Swirls of Water Discharged from the Drainage of CFR-600

3. Who Owns Spent Fuel?

(1) Issue of ownership of spent fuel from an FBR

Who owns the right to reprocess spent fuel or the right to use the plutonium obtained through the reprocessing? Whether the right belongs to the fuel supplier or the operator of the nuclear reactor is a critical issue in terms of international nuclear non-proliferation. Especially in the case of an FBR, the ownership of spent fuel is a complicated issue for the following reasons:

(1) Plutonium extracted from spent fuel is nuclear weapons-grade, which means it has the potential of contributing to nuclear proliferation.

(2) Core and blanket fuels are often purchased from different suppliers.

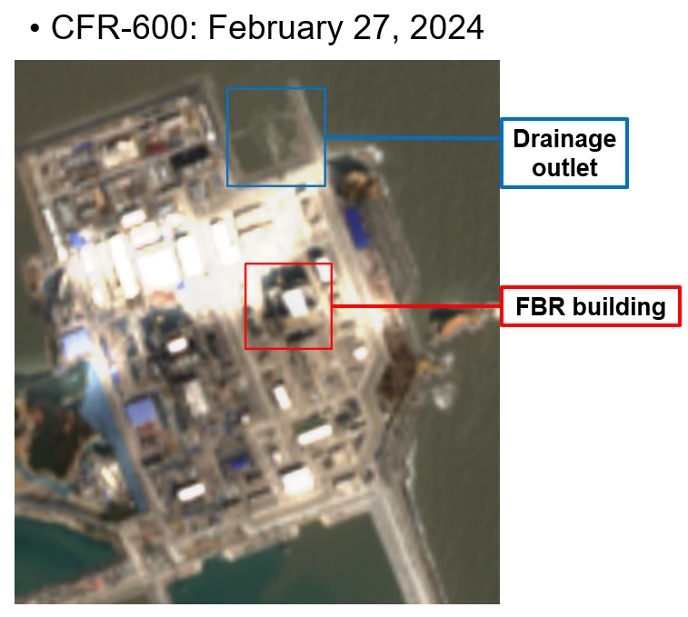

As Figure 2 shows, plutonium-239, which provides excellent energy releases, comprises over 90

percent of weapons-grade plutonium extracted from blanket fuel for an FBR. On the other hand, plutonium from reprocessed spent fuel for a regular nuclear reactor (light-water reactor), which is the type of reactor commonly used worldwide, is composed of around more than 50 percent plutonium-239 and contains many other isotopes. This plutonium could be used for the production of nuclear weapons, yet it is less than suitable.

Figure 2: Plutonium Composition Suitable for the Production of Nuclear Weapons

This table has been created by the author of this report referring to the article “Comparison of Plutonium Composition for an Atomic Bomb and Industrial Use” on the website of Nuclear Energy Encyclopedia ATOMICA and other sources.

Furthermore, another issue arises when core and blanket fuels are provided by different suppliers. Only a few countries have the technology to produce core fuel (e.g., Russia and France), which uses high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU) or mixed-oxide (MOX) fuel composed of uranium and plutonium. Blanket fuel uses uranium-238, which comprises over 99 percent of naturally occurring uranium, and thus there is a large surplus of it. China apparently supplies itself with blanket fuel for CFR-600 from its internal source.[5] In the case where core and blanket fuel suppliers are different, who owns the right to use plutonium extracted from reprocessed spent fuel in the blanket region, and how should the ownership be determined? Depending on the definition, the country that operates the reactor may not be allowed to extract or use plutonium at its own discretion.

(2) Idea of neutron contribution

The agreed minutes to the Japan-US Nuclear Cooperation Agreement signed in 1988 offers one idea.[6] At the time, the U.S. government and Congress were critical of Japan’s planned nuclear fuel cycle, which was to operate an FBR for reprocessing spent fuel in order to extract and reuse plutonium and thus seemed unsuitable for nuclear non-proliferation. Hence, the revision of the Japan-US Nuclear Cooperation Agreement in the 1980s focused on how the United States and the international community would watch Japan’s use of plutonium. As a result, the idea of “neutron contribution” was adopted to address the issue of ownership of spent fuel in the blanket region of an FBR. The logic of the idea is that since plutonium from the blanket region is generated by neutrons released from nuclear materials in the core fuel, the supplier of the nuclear materials for the core region is acknowledged to own the right to a certain percentage of plutonium from the blanket region.[7] With little domestic production of natural uranium, Japan imported fuel for its FBR from France and other countries. Hence, the idea of nuclear contribution was to not entitle Japan to reprocess the blanket fuel to extract and use plutonium at its own discretion. In other words, the idea of neutron contribution guaranteed that Japan would use plutonium in accordance with the legally binding bilateral nuclear accords the country signed with the United States and France as well as with the safeguards agreement signed with the IAEA (for regular inspections of nuclear facilities). Neutron contribution received certain recognition as an idea that contributed to nuclear non-proliferation.[8]

4. Issues Posed by Russia’s Involvement in China’s FBR

China insists that plutonium produced by CFR-600 is for civilian use, yet the country has disclosed to the international community nothing about what the plant does. If China intended to divert its plutonium to military use, how would Russia become involved in the reprocessing of spent fuel from the FBRs by signing an agreement with China? When I asked experts on nuclear non-proliferation and nuclear arms control in Japan and other countries (including Russia), their opinions were divided. One view was that China’s expanded nuclear armaments would downgrade the relative status of Russia, which as a nuclear power has defined the principles of arms control worldwide together with the United States. Hence, some said that Russia might impose restrictions on China’s reprocessing of spent fuel from the FBR and use of plutonium. In that case, the principle of neutron contribution might be partially considered. The other view was that given the current difference in national strength between China and Russia, Russia might have no choice but to allow China to reprocess spent fuel.[9] In either case, in regard to CFR-600, we should keep watching for what Russia intends and decides to do, in addition to whether China will achieve stable operation of the plant to establish its technology for reprocessing spent fuel to obtain large quantities of plutonium.

The reason for the need to examine what China and Russia intend to do is that the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) gives these two countries special permission to have nuclear arms and that they are not required to accept IAEA inspections of the transfer of nuclear materials and the use of plutonium. The details of the agreement regarding the FBRs signed between them have not been, and will unlikely be, disclosed. Their agreement does not pose the threat of nuclear proliferation to non-nuclear-weapon states (“horizontal proliferation”), the threat that led to the revision of the Japan-US Nuclear Cooperation Agreement. However, the transfer of nuclear materials between China and Russia this time will potentially lead a nuclear power to dramatically increase its nuclear weapons capability (“vertical proliferation”), affecting the security of Northeast Asia and, eventually, of the world. The international community should work on how to ensure the transparency of nuclear materials transferred between nuclear-weapon states. Japan should take the lead in calling on the world to discuss this issue, as it is the only non-nuclear-weapon state that is allowed to operate FBRs and reprocess spent fuel from the reactors to extract plutonium and its security is directly affected by any developments in China’s military affairs.

1 “MILITARY AND SECURITY DEVELOPMENTS INVOLVING THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA 2023” Page 104, Office of the Secretary of Defense [https://media.defense.gov/2023/Oct/19/2003323409/-1/-1/1/2023-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF]

2 “China and Russia sign fast-neutron reactors cooperation agreement” March 22, 2023 [https://www.world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/China-and-Russia-to-cooperate-on-fast-neutron-reac]

3 The numbers of nuclear warheads are cited from “SIPRI YEARBOOK 2023” published by Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) [https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/YB23%2007%20WNF.pdf]

4 “IAEA Report DOC CFR600,” the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) [https://aris.iaea.org/PDF/CFR-600.pdf]

5 China’s uranium enrichment business has a worldwide market share of over 11 percent. Uranium enrichment is the process of separating fissile uranium-235 and non-fissile uranium-238 to increase the proportion of uranium-235. China has large quantities of uranium-238 in its domestic locations. Reference: “Analysis of Worldwide Market Shares in the Uranium Enrichment Industry” [https://deallab.info/enriched-uranium/]

6 The official name is the Implementing Agreement Between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of Japan pursuant to Agreed Minutes and Article 11 of Their Agreement for Cooperation Concerning Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy July 2, 1988.

7 “Bilateral nuclear cooperation agreements and flag control on nuclear material and other materials” Tsuboi Hiroshi and Keiji Kanda, Journal of the Atomic Energy Society of Japan, Vol. 43, Issue 8, 2001 [https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jaesj1959/43/8/43_8_806/_pdf/-char/ja] [https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jaesj1959/43/8/43_8_806/_article/-char/en]

8 Same as above

9 From interviews with six experts on nuclear non-proliferation and arms control (one in Russia, two in the United States, and three in Japan) conducted from April 2 to 26 in 2024.