The Iranian Nuclear Development Issue and The Concept of a Middle East Nuclear Consortium

Yuki Kobayashi

* The following article is the English translation of the Japanese article originally published at December 24, 2025.

1. The Turbulent Situation in Iran and the Concept of a Middle East Nuclear Consortium

The situation in Iran, suspected of pursuing nuclear development such as high-level uranium enrichment, remains in turmoil. In June 2025, Israel and the United States carried out airstrikes on Iran’s nuclear-related facilities with the aim of preventing the development of nuclear weapons1. In August, the United Kingdom, France, and Germany initiated the “snapback” procedure to reinstate sanctions, arguing that Iran had violated the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)—the nuclear agreement concluded in 2015 between Iran and six countries, including Germany as an addition to the permanent members of the UN Security Council. By the end of September, sanctions against Iran were reimposed2, prompting Iran to suspend cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in protest.

In this context, one proposed solution to the Iranian nuclear issue has been the establishment of a regional consortium involving neighboring countries, under which uranium enrichment would be conducted jointly by multiple states. This idea has quietly emerged and is attracting attention. According to U.S. media reports, the proposal was put forward by Iran to the United States as a means of bridging the gap between Washington’s demand for a complete halt to Iranian uranium enrichment and Tehran’s insistence on retaining its right to the peaceful use of nuclear energy3. Former Iranian government officials have also acknowledged the existence of such a concept. On November 3, 2025, former Vice President Mohammad Javad Zarif delivered a speech at the 63rd Pugwash Conference held in Hiroshima, unveiling the idea of establishing the “Middle East Network for Atomic Research and Advancement” (MENARA), aimed at promoting the peaceful use of nuclear energy and advancing nuclear non-proliferation4.

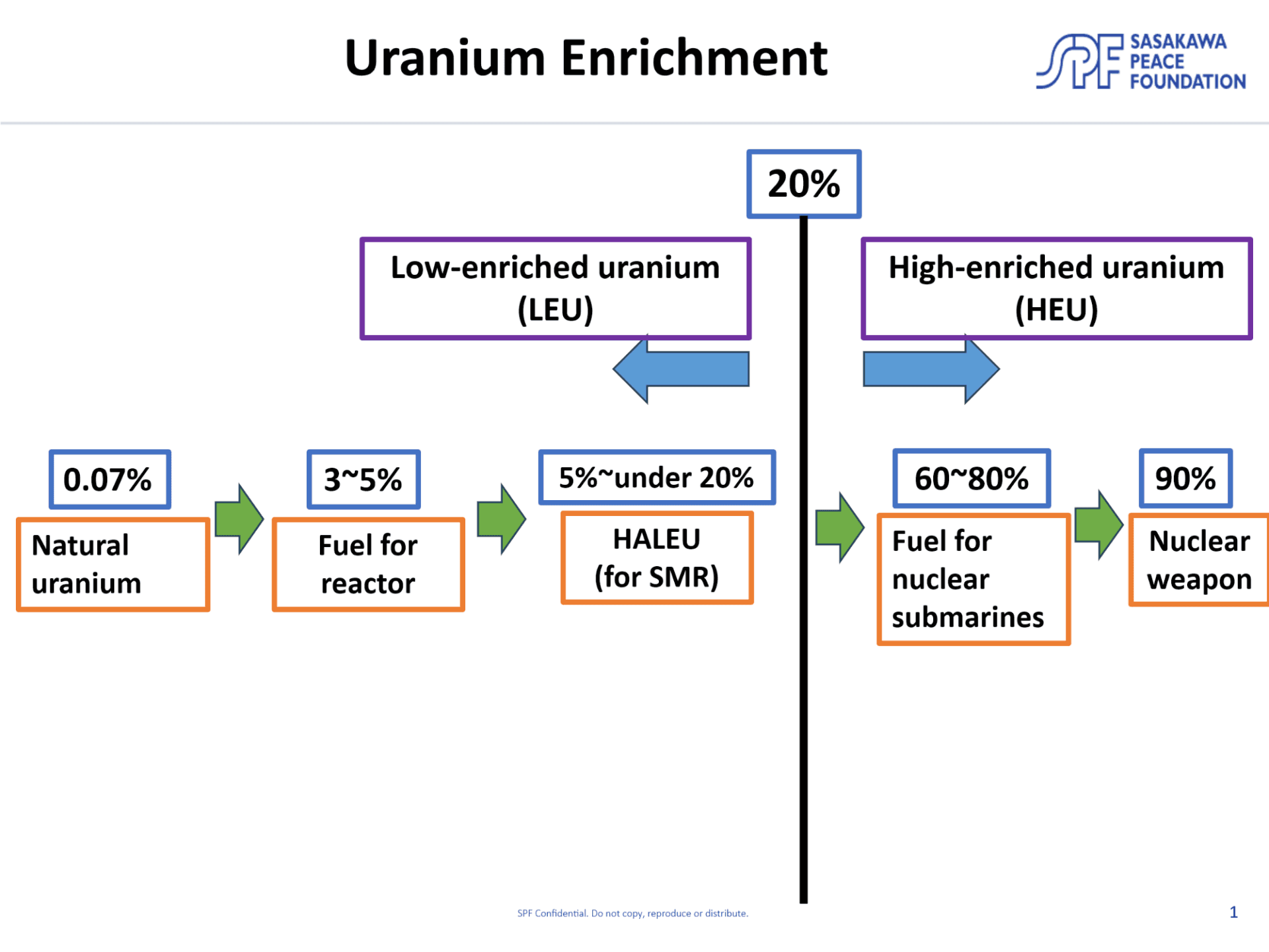

Iran’s current trajectory cannot escape the charge of exceeding the bounds of peaceful nuclear use, as it has raised the level of uranium enrichment to nearly 60 percent—approaching weapons-grade (see figure below). Should Iran, in defiance of renewed Western sanctions, withdraw from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and persist in its nuclear development, major neighboring powers such as Saudi Arabia may also move toward nuclear development, potentially triggering a “domino effect” of nuclear proliferation across the Middle East and beyond. In this context, the concept of a regional consortium warrants examination as a possible solution that could reconcile the prevention of nuclear proliferation with the peaceful use of nuclear energy.

This paper will first provide an overview of Iran’s uranium enrichment activities and the responses of Israel and Western countries. It will then examine Iran’s proposed consortium concept, reviewing the history of consortia in the nuclear field and incorporating perspectives from the United States—likely to be a principal negotiating party—as well as from nuclear energy and non-proliferation experts. Finally, it will consider what the international community, including Japan, should undertake in pursuit of resolving the Iranian nuclear issue.

2. Iran’s Suspected Nuclear Development and the Response of Western Countries

(1) Uranium Enrichment and Nuclear Weapons

Whether for civilian power generation or military purposes, the process of uranium enrichment is indispensable. Natural uranium contains only 0.7 percent of uranium-235, the isotope that undergoes fission and releases vast amounts of thermal energy, while the remainder consists of uranium-238, which does not readily undergo fission. Consequently, it is necessary to separate uranium-235 using centrifuges and increase its proportion through processing. Specifically, natural uranium ore is chemically treated to produce a yellow powder known as “yellowcake,” which is then combined with fluorine to form uranium hexafluoride. When heated, uranium hexafluoride becomes gaseous and is fed into centrifuges5. As shown in the figure, low-enriched uranium (LEU) containing 3–5 percent uranium-235 is typically used for nuclear reactors. Once the technology to enrich uranium to around 5 percent is established, it becomes technically possible to produce highly enriched uranium (HEU) at 90 percent concentration, suitable for nuclear weapons. A uranium-based nuclear weapon is estimated to require approximately 22 kilograms of HEU per device.

Although the conversion to uranium hexafluoride, its supply to centrifuges, and the production of highly enriched uranium may be unfamiliar to those outside the nuclear field, understanding the outline of the enrichment process and the applications corresponding to different enrichment levels is essential. This knowledge is necessary for grasping the core of the Iranian issue and for considering the division of roles among countries in the proposed Middle East Nuclear Consortium.

Figure: Overview of Uranium Enrichment

Source: Compiled by the author.

Iran has engaged in the manufacture of centrifuges and uranium enrichment at Natanz and Fordo, located in the western part of the country. Since 2018, when the first Trump administration in the United States unilaterally withdrew from the JCPOA, Iran has significantly exceeded the enrichment cap of 3.67 percent stipulated under the agreement, raising the enrichment level to as high as 60 percent. According to a report delivered by IAEA Director General Rafael Grossi to the United Nations Security Council on June 20, 2025, Iran’s stockpile of uranium enriched to 60 percent has already surpassed 400 kilograms6. As shown in the figure, uranium classified as weapons-grade requires enrichment to 90 percent, but Iran is estimated to be capable of reaching that level within approximately three weeks.

(2) Israeli and U.S. Airstrikes and the Move by the UK, France, and Germany to Reapply Sanctions

On June 13, 2025, Israel launched attacks across Iran, including strikes on nuclear-related facilities, claiming the objective of halting Iran’s nuclear development. Furthermore, in the early hours of June 22 (local time), the United States attacked three Iranian nuclear facilities, with President Trump boasting that they had been “completely destroyed.”7 The U.S. participation in the airstrikes was deemed essential because the uranium enrichment plants constructed deep within fortified rock formations—such as those at Fordo—could only be destroyed through the use of the GBU-57, a ground-penetrating bomb commonly known as the “bunker buster.” The GBU-57 is capable of penetrating more than 60 meters underground, and the United States is the only country in the world to possess a ground-penetrating bomb of this capability. As noted below, the U.S. Department of Defense acknowledged the use of the bunker buster in the course of the strikes.

After proceeding quietly and with minimal communication for 18 hours from the U.S. to the target area, the first of seven B-2 Spirit stealth bombers dropped two 30,000-pound GBU-57 Massive Ordnance Penetrator "bunker buster" bombs at the Fordo site yesterday at approximately 6:40 p.m. EDT…

Ref: U.S. Department of Defense “Hegseth, Caine Laud Success of U.S. Strike on Iran Nuke Sites” 22 June 2025.

The bunker buster was also used in the attack on the underground uranium enrichment facility at Natanz. As shown in the satellite image below (upper center), cluster-like craters—believed to be the result of bunker buster strikes—can be clearly identified.

Satellite Image: Natanz Nuclear Facility Immediately After U.S. Strikes

Source: Google Earth

Contrary to President Trump’s remarks, the recent airstrikes did not succeed in completely destroying the uranium enrichment facilities at Fordo and Natanz. Moreover, uranium already enriched to 60 percent had reportedly been relocated by Iran prior to the strikes and remained intact8. As a result, the possibility of Iran continuing its nuclear development has not been eliminated.

In response, the three European parties to the JCPOA—the United Kingdom, France, and Germany—expressed heightened concern and, on August 28 of the same year, formally notified the United Nations Security Council of Iran’s violation of the agreement. The JCPOA had originally stipulated that all sanctions on Iran would be fully terminated on October 18, 2025, but it also provided that sanctions could be reinstated in the event of a significant Iranian breach9. Although China and Russia submitted proposals to the Security Council calling for the continuation of sanctions relief, these were rejected, and sanctions were reinstated on September 28 (Japan time). The Iranian Ministry of Foreign Affairs strongly protested, declaring that “the reactivation of sanctions is unjustified and imposes no obligations on Iran or any other UN member state10.

3. The Concept of a Middle East Nuclear Consortium

Amid escalating tensions surrounding Iran, the idea of a regional consortium was reportedly proposed during negotiations between Iran and the United States, which had withdrawn from the JCPOA, just prior to the Israeli and U.S. airstrikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities11. While the specific details remain unclear, some aspects of the proposal can be gleaned from the speech delivered by former Vice President Zarif in Hiroshima.

Another initiative that a colleague and I proposed in the Guardian a couple of months ago is the Middle East Network for Atomic Research and Advancement, or MENARA—a term that in Arabic means “beacon.” MENARA envisions a collaborative regional network dedicated to non-proliferation while harnessing peaceful nuclear cooperation. This network should include an enrichment consortium, bringing together existing capabilities into a collective peaceful and transparent effort. Crucially, the network would also incorporate robust oversight mechanisms, including mutual inspections to foster trust through transparency. Open to all Middle Eastern countries willing to renounce nuclear weapons and adhere to strict safeguards, its mission is to reframe the nuclear question from a source of tension into a platform for collaboration.

Ref: Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs “Keynote Speech by Dr. Javad Zarif at the 63rd Pugwash Conference Hiroshima” November 3, 2025.

Zarif’s proposal emphasized the following points:

- It would constitute a regional network dedicated to the peaceful use of nuclear energy and the prevention of nuclear proliferation.

- Uranium enrichment—most closely associated with concerns over nuclear weapons development—should serve as the central pillar of regional cooperation, thereby enhancing transparency in nuclear activities.

- In addition to IAEA safeguards (inspections of nuclear facilities and materials), mutual monitoring of nuclear use among Middle Eastern countries should be introduced.

- Membership should be open to all Middle Eastern states that renounce nuclear weapons and comply with safeguard obligations.

This vision appears to have been seriously considered not only by Zarif but also by reformist politicians and bureaucrats within Iran who are regarded as prioritizing international cooperation.

At the same time, however, Iran’s parliament is currently dominated by hardline conservatives, whose insistence on never relinquishing uranium enrichment and the right to peaceful nuclear use has grown stronger. Taking these domestic circumstances into account, Zarif underscored that Article IV of the NPT stipulates the “inalienable right” of non-nuclear-weapon states to the peaceful use of nuclear energy, and reiterated that Iran would not abandon this right. He sharply criticized the U.S. and Israeli airstrikes, declaring that they not only violated Article IV but also undermined the very foundation of the NPT12.

4. Feasibility and Challenges of the Consortium Concept

Zarif’s proposed consortium reflects an apparent intention to address concerns over Iran’s uranium enrichment, yet it remains uncertain whether such a plan could secure consensus within Iran itself. Moreover, ambiguities persist within the proposal. For instance, the participating countries in the consortium have not been specified, nor has it been clarified how the various stages of uranium enrichment would be divided among them. Consequently, U.S. Middle East specialists and associations of nuclear scientists have begun offering evaluations of the consortium concept as well as new proposals.

(1) Evaluation from the typology of international consortiums by The Washington Institute

Researchers at The Washington Institute, which primarily provides policy recommendations on Middle Eastern affairs, have attempted to assess Iran’s proposed consortium by situating it within typologies of international consortia.The many consortium ideas that have been proposed to deal with the Iran enrichment quandary can be grouped into three general categories:

Financial stake for services rendered. In this model, participants pay for a stake in a company, receive enriched uranium in return, but do not participate in all aspects of production…

Split technical participation. In this model, consortium partners identify parts of the fuel production process to be done by each member and share the resulting product. For example, one member mines the uranium, another converts it into enrichable form, another produces the fuel, and yet another handles waste maintenance….

Black-box operations. In this model, a country could house an enrichment facility but not be involved in the technological aspects of its work. Such a facility could be under foreign control and operation, as seen with Urenco’s plant in the United States…

Ref: The Washington Institute for Near East Policy “An “Enrichment Consortium” Is No Panacea for the Iran Nuclear Dilemma” June 5, 2025.

This typology is based on analyses of the international nuclear consortia that emerged in Europe during the 1970s. Until then, apart from the two major nuclear-weapon states—the United States and the Soviet Union—there were no commercial uranium enrichment facilities. Within the Western bloc, the United States had monopolized the supply of enriched uranium, thereby effectively managing the nuclear energy use of other countries. However, in the 1970s, momentum grew in Europe for self-sufficiency in uranium enrichment and for greater autonomy in nuclear policy. To balance the need to share the substantial costs of infrastructure construction with the goal of preventing proliferation risks through mutual monitoring, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and West Germany established URENCO in 1971 to engage in uranium enrichment. Each of the three countries constructed its own enrichment plant using the centrifuge method. In 1973, France, together with Belgium, Spain, and Sweden, established EURODIF, which built a commercial uranium enrichment facility in France employing the gaseous diffusion method. This facility began operations in the early 1980s13.

URENCO continues to operate today, accounting for more than 30 percent of the global uranium enrichment market, making it the second-largest player worldwide after a subsidiary of Russia’s state-owned nuclear corporation Rosatom. It is regarded as a successful example of a consortium. EURODIF, by contrast, was dissolved in 1991, but its operations were taken over by France’s Areva (now Orano), which has continued uranium enrichment using URENCO’s centrifuge technology14.

The two European cases are closest in form to Type 1 consortia, and their success can be attributed to several factors: the existence of sufficient demand for enriched uranium within the region; the shared objectives among participating countries of distributing the high costs of nuclear infrastructure, preventing proliferation risks through mutual oversight, and reducing dependence on the United States15.

By contrast, in the Middle East, nuclear power generation remains in its infancy, and demand for uranium enrichment cannot be expected to reach sufficient levels. Moreover, Iran shows little willingness to relocate its core enrichment technologies and major processes abroad. The United States, for its part, opposes any arrangement in which the majority of enrichment processes would be conducted within Iran. It remains unclear whether the consortium concept could bridge these differences. In any form, the fact that Iran would retain enrichment processes and technological know-how means that concerns over potential military diversion cannot be fully eliminated. For these reasons, The Washington Institute has concluded that the consortium cannot serve as a panacea16.

(2) The Consortium Proposal Suggested by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

Seeking solutions to these challenges is the U.S.-based Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The journal is known for addressing issues of science and technology that pose threats to human society, particularly weapons of mass destruction such as nuclear arms, and for annually publishing the “Doomsday Clock,” which symbolizes the time remaining until potential human catastrophe. Taking into account the economic capacities of Middle Eastern countries, their geographic characteristics, and the presence or absence of nuclear power plants—including construction plans—the Bulletin has proposed that the initial member states of such a consortium should be Iran, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, and has defined the roles of each country as follows.Iran: The development, production and operation of centrifuges for uranium enrichment has been the focus of Iran’s program and of its technological accomplishments…. Iran would maintain research, development, and manufacturing/production of centrifuges and operation of research and development test or pilot cascades. These activities could continue at its current nuclear complex.

Oman: An obvious candidate to host a new uranium enrichment plant for the regional consortium would be Oman, across the Gulf of Oman from Iran and bordering on both Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Oman has repeatedly acted as a diplomatic intermediary and venue for discussions between Iran and the United States.

Saudi Arabia: Uranium mining and imports of uranium and uranium ore concentrate; conversion to uranium hexafluoride (UF6); the stockpiling of enriched uranium product and tails; and processing the enriched uranium back into uranium oxide for fabrication into fuel would all take place in Saudi Arabia…. As the richest country in the region, Saudi Arabia could become the primary financier and potentially a major customer for the output of the regional enrichment plant.

United Arab Emirates: The management headquarters of the multinational consortium could be in the United Arab Emirates. The UAE also could be an early client for consortium uranium enrichment services and for fuel supply from the LEU fuel store in Saudi Arabia.

Ref: Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists “A nuclear consortium in the Persian Gulf as a basis for a new nuclear deal between the United States and Iran” June 2, 2025.

Like Zarif’s proposal, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists emphasizes that the consortium should be open to the region, allowing participation by countries beyond the four initially identified, should they wish to join. Turkey and Egypt, both advancing nuclear power plant construction plans, are considered strong candidates17.

Nevertheless, as researchers at The Washington Institute have pointed out, it is unlikely that Middle Eastern countries alone could ensure the sustainability of such a consortium. The Bulletin therefore calls for robust involvement by the international community. In particular, it stresses that approval of any consortium agreement through a resolution of the UN Security Council and ratification by the U.S. Congress would be indispensable. This recommendation reflects the precedent of 2015, when Iran and the P5+1 (the permanent members of the UN Security Council plus Germany) reached agreement on the JCPOA, but the U.S. Congress declined to ratify it, enabling President Trump in 2018 to declare a unilateral withdrawal. Regarding a new consortium, the Bulletin notes that if a Republican president were to support the agreement through negotiations with Iran, it might be possible to secure the two-thirds majority in the Senate required for ratification18.

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has also proposed measures to prevent Iran from diverting uranium enrichment technology for military purposes. During the transitional period toward a consortium, it suggests that, under IAEA supervision, highly enriched uranium should be diluted to below 5 percent and then used in Iran’s operating nuclear power plants. While permitting Iran to develop and manufacture centrifuges, the proposal stipulates that the choice of centrifuge models would be determined by the consortium, with Iran having no authority in the selection process.

Although the Bulletin’s proposal reflects perspectives characteristic of an organization well-versed in nuclear engineering—such as the division of roles in the enrichment process—it does not provide a definitive answer to the question raised by The Washington Institute: whether concerns over military diversion would persist so long as Iran retains enrichment processes and technological expertise. Furthermore, regarding the international involvement necessary to ensure the sustainability of the consortium, prospects remain bleak given that the UN Security Council itself has fallen into dysfunction due to internal divisions.

5. Conclusion

As the preceding analysis has demonstrated, the consortium initiative is being seriously considered by Iran itself and by U.S. experts engaged in negotiations as one possible means of addressing the Iranian nuclear issue. However, at this stage, discussions remain confined to Iran and certain circles in the United States; substantive debate among Middle Eastern countries has yet to begin, and the path to realization is far from straightforward. This section summarizes the background, substance, and proposals of the initiative, and concludes with reflections on how Japan might contribute from its own perspective.

- Amid escalating tensions over Iran, the concept of a Middle East Nuclear Consortium was proposed as one possible solution shortly before potential strikes by Israel and the United States on Iran’s nuclear facilities.

- Within Iran, the idea is being seriously examined, at least among reformist factions that prioritize international cooperation.

- Yet, as indicated in the proposal by former Vice President Zarif, details such as the composition of member states and the division of roles in uranium enrichment remain undefined.

- The Washington Institute, drawing on comparative studies of past international nuclear consortia, argues that a Middle Eastern consortium faces few prospects for success. Moreover, Iran has already accumulated enrichment technology, making it difficult to dispel concerns over potential military diversion.

- Conversely, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has advanced its own proposals regarding consortium membership, suggesting room for further consideration, though without articulating a clear roadmap for implementation.

Given these circumstances, it is essential to engage the principal stakeholders—Iran, the United States, the parties to the JCPOA, and Middle Eastern states—in concrete work toward operationalizing the consortium, including the allocation of roles in the enrichment process. From Japan’s standpoint, what can be done to support this process and contribute to resolving the Iranian nuclear issue? Above all, Japan’s role—independent of the consortium initiative—should be to persuade Iran to remain within the framework of the NPT, taking into account its relationship with the United States. Japan has, since the postwar period, been one of the countries that most fully exercised the right to peaceful use of nuclear energy under close cooperation with the IAEA, and, despite being a non-nuclear-weapon state, obtained U.S. approval to acquire reprocessing technology for extracting plutonium from spent fuel. Sharing this history with Iran and persistently urging it to cooperate with the IAEA while adhering to peaceful use within the NPT framework is imperative. Japan’s long-standing record of maintaining amicable relations with Iran even after the 1979 revolution further strengthens its ability to play such a role. Should the consortium initiative materialize, Japan could also contribute by providing safeguards technologies developed in cooperation with the IAEA to prevent nuclear proliferation, as well as by supporting capacity-building for nuclear regulatory authorities in Middle Eastern countries.

The current situation remains challenging, yet it is to be hoped that diverse ideas and proposals—including the consortium initiative—will continue to be debated, paving the way toward a resolution of the Iranian nuclear issue.

(End)

- “'Historically Successful' Strike on Iranian Nuclear Site Was 15 Years in the Making,” U.S. Department of Defense, June 26, 2025, <https://www.war.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/4227082/historically-successful-strike-on-iranian-nuclear-site-was-15-years-in-the-maki/>(accessed on November 6, 2025)(本文に戻る)

- “Completion of UN Sanctions Snapback on Iran,” U.S. Department of State, September 27, 2025, <https://www.state.gov/releases/office-of-the-spokesperson/2025/09/completion-of-un-sanctions-snapback-on-iran>(accessed on November 6, 2025)(本文に戻る)

- Farnaz Fassihi, “Iran Proposes Novel Path to Nuclear Deal With U.S.,” The New York Times, May 13, 2025, <https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/13/world/middleeast/iran-us-nuclear-talks.html>(accessed on November 6, 2025(本文に戻る)

- “Keynote Speech by Dr. Javad Zarif at the 63rd Pugwash Conference Hiroshima, 3 November, 2025,” Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs (See pager 5 for reference to the consortium) <https://pugwash.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/251103-mjz-pugwash-hiroshima.pdf>(accessed on November 6, 2025)(本文に戻る)

- See, e.g., JNFL, "Process at Uranium Enrichment Plant. <https://www.jnfl.co.jp/ja/business/about/uran/summary/process.html>(accessed on November 6, 2025)(本文に戻る)

- “IAEA Director General Grossi’s Statement to UNSC on Situation in Iran,” IAEA, June 20, 2025, <https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/statements/iaea-director-general-grossis-statement-to-unsc-on-situation-in-iran-20-june-2025> (accessed on November 6, 2025)(本文に戻る)

- “President Trump Delivers Address to the Nation, June 21, 2025,” The WHITE HOUSE, June 21, 2025, <https://www.whitehouse.gov/videos/president-trump-delivers-address-to-the-nation-june-21-2025/>(accessed on November 6, 2025)(本文に戻る)

- See SPF CHINA OBSERVER “Preliminary Assessment of Iran’s Nuclear Development and the Attacks on Nuclear-Related Facilities” July 23, 2025. <https://www.spf.org/spf-china-observer/en/eisei/eisei-detail013.html>(accessed on November 6, 2025)(本文に戻る)

- "Re-application of the Security Council Sanctions Resolution against Iran (Foreign Minister's Statement, in Japanese)," Ministry of Foreign Affairs, <https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/press/danwa/25/pageit_000001_00003.html>(accessed on November 6, 2025)(本文に戻る)

- “US, European attempts to restore UNSC resolutions against Iran ‘illegal’: Baghaei,” Islamic Republic News Agency, September 29 2025, <https://en.irna.ir/news/85952546/US-European-attempts-to-restore-UNSC-resolutions-against-Iran>(accessed on November 6, 2025)(本文に戻る)

- See footnote 3.。(本文に戻る)

- Mr. Zarif responded to questions from the media and research organizations after his speech in Hiroshima, Japan, on November 3, 2025, and agreed to be quoted in his remarks.(本文に戻る)

- ATOMICA, The Encyclopedia of Nuclear Energy "Uranium Enrichment Facilities of the World (in Japanese) <https://atomica.jaea.go.jp/data/detail/dat_detail_04-05-02-02.html>(accessed on November 6, 2025)(本文に戻る)

- “An “Enrichment Consortium” Is No Panacea for the Iran Nuclear Dilemma,” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, June 5, 2025, <https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/enrichment-consortium-no-panacea-iran-nuclear-dilemma> (accessed on November 6, 2025)(本文に戻る)

- Same as above.(本文に戻る)

- Same as above.(本文に戻る)

- Frank von Hippel et al., “A nuclear consortium in the Persian Gulf as a basis for a new nuclear deal between the United States and Iran,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, June 2, 2025, <https://thebulletin.org/2025/06/a-nuclear-consortium-in-the-persian-gulf-as-a-basis-for-a-new-nuclear-deal-between-the-united-states-and-iran/> (accessed on November 6, 2025)(本文に戻る)

- Same as above.(本文に戻る)