Contents *Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited

SPF China Observer

HOMENo.67 2026/01/30

Developments Surrounding Launch of Taiwan’s Indigenous Sub Hai Kun

—Background Behind Commissioning Delay and Its Implications for Taiwan’ Security—

Introduction

In recent years, the Taiwan Strait has seen increasingly aggressive military activities by China, which regards Taiwan as a target to be “reunified” as part of its own territory.[1] Meanwhile, Taiwan has been governed since 2016 by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), which opposes “reunification” with China, and has promoted expansion of the defense budget as well as the domestic production of weapon systems in order to counter China’s military pressure.[2]

Against this backdrop, Taiwan has placed particular emphasis on the development of indigenous submarines as a key component of its weapon indigenization efforts. Surrounded by the sea, Taiwan is heavily dependent on maritime routes for the procurement of supplies from overseas and thus possesses geographical vulnerability to maritime blockades. Submarines, by contrast, are regarded as a critical capability for breaking such blockades,[3] are positioned as one element of long-range strike capabilities, and are also seen as contributing to the deterrence of China’s penetration of what it calls the first island chain.[4]

Based on such awareness, Taiwan began construction of its first indigenous submarine, Hai Kun (named after a mythical sea creature appearing in the Zhuangzi collection of works of Daoism), in 2020 under the Tsai Ing-wen administration, and a launching ceremony was held in September 2023. Although Hai Kun had been scheduled for induction into the armed forces in November 2025,[5] the vessel remained at the stage of sea trials as of late December 2025, when this paper was written; not only has it yet to enter service, but even its dive trials have not been conducted.

This paper analyzes the causes of the delay in Hai Kun’s commissioning and the security implications arising from that delay. As a prerequisite for this analysis, it first reviews the background behind Taiwan’s pursuit of indigenous submarine construction and provides an overview of the key characteristics of the vessel.

1. Prehistory of Indigenous Submarine Construction Project

At present, the Taiwanese Navy operates four submarines. Of these, two are Hai Shih-class vessels sold by the United States in the 1950s, while the remaining two are Chien Lung-class submarines imported from the Netherlands in the 1980s. As such, all submarines currently in Taiwan’s inventory are foreign-built, and it can be noted that they are all aging out-of-date vessels with exceptionally long service lives.

Because of the difficulty of procuring submarines from abroad, Taiwan has long pursued the localization of submarine construction.[6] In the 1990s, during the Lee Teng-hui administration (1987–2000), joint development with Dutch companies was considered, but the initiative ultimately collapsed due to pressure from China. Under the Chen Shui-bian administration (2000–2008), Taiwan explored the possibility of joint development with companies from Germany, Israel and other countries. However, the plan was abandoned after President Chen Shui-bian opposed local production. It should also be noted that the US Bush administration (2001–2009) approved the sale of eight diesel-powered submarines to Taiwan under the Chen government, but the transaction ultimately failed to materialize.[7] This was due to Taiwan’s inability to secure sufficient funding amid partisan confrontation as well as because of the fact that the United States was no longer building diesel-powered submarines at the time, and expectations of strong opposition from China. The subsequent Ma Ying-jeou administration (2008–2016) initially considered importing submarines from the United States as well. However, having failed to receive a positive response from Washington, it formulated an “Integrated Research Program on Key Technologies for Indigenous Submarine Construction” in 2014, signaling a policy shift toward localization. This policy was carried over into the Tsai Ing-wen administration (2016–2024), following the transfer of power from the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) to the DPP and became the foundation of the Hai Kun construction program.

As outlined above, Taiwan’s efforts to pursue indigenous submarine construction reveal a consistent pattern regardless of the ruling party: Taiwan has sought to localize submarine production but, lacking its own proprietary know-how, it has been compelled to rely on joint development with foreign firms. As discussed later, a similar situation can be observed in the construction of Hai Kun, where this reliance has become one of the factors contributing to its delayed commissioning.

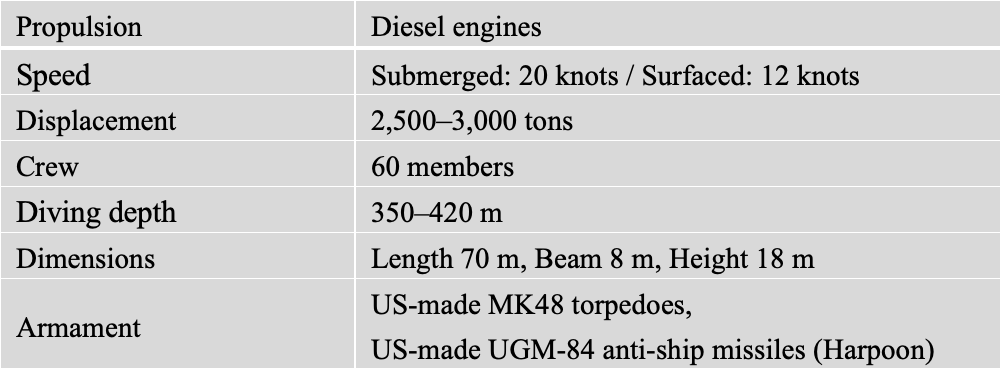

2. Overview of Hai Kun

Given these developments, funding for Hai Kun’s construction was allocated in 2016 under the Tsai Ing-wen administration, construction was initiated in November 2020, and, as noted above, a launching ceremony was held in September 2023. The principal specifications of Hai Kun are shown in the table below.[8]

The construction was carried out primarily by CSBC Corporation, Taiwan (hereinafter “CSBC”), a Taiwanese state-owned enterprise. The onboard hardware and software, however, involved procurement from foreign firms, many of which were US companies. For example, Lockheed Martin reportedly supplied the combat management system, Northrop Grumman provided the sonar, and L3Harris Technologies delivered the optronic mast—an apparatus equipped with electronic and infrared cameras to observe the external environment in place of a traditional periscope—as well as communications and electronic systems.[9] Taiwan’s procurement of weapons from overseas has long been constrained, except for the United States, which has the Taiwan Relations Act enacted in 1979 stipulating the provision of “defensive arms” to Taiwan (Section 2(a)), given other countries’ considerations of their relations with China. Nevertheless, in the development and construction of Hai Kun, companies not only from the United States but also from Australia, Canada, India, the United Kingdom, Spain, and South Korea reportedly provided technology, personnel, and components.[10] In this sense, the project can be characterized as de facto international joint development.

Su Tzu-yun, Research Fellow at Taiwan’s Institute for National Defense and Security Research, positively assessed the provision of critical technologies by Western countries in the Hai Kun construction, describing it as “symbolic of how European countries view Taiwan.” Associate Professor Lin Ying-yu of Tamkang University likewise pointed out that, in the process of integrating technologies from multiple countries for the Hai Kun project, Taiwan is likely to advance the training of submarine-related personnel in the future, which could in turn contribute to the development of its defense industry.

The construction cost of Hai Kun amounts to a total of 49.3 billion New Taiwan dollars (NTD) . In addition, Taiwan plans to build seven more indigenous submarines of the same class by 2038. The construction cost for each of these submarines is estimated at 20 billion NTD , bringing the total projected cost to 189.3 billion NTD by the time all eight indigenous submarines enter service. For reference, the construction cost of the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force’s 3,000-ton-class submarine Raigei, which entered service in October 2020, was approximately 16 billion NTD,[11] while that of its sister ship Taigei, commissioned in March 2025, was about 14 billion NTD.[12] These figures are lower even when compared with Hai Kun’s construction cost as well as that of its follow-on vessels of the same class.

3. Factors Behind Delayed Commissioning

Thus, although the Hai Kun development program was a joint project involving companies from multiple countries, including the United States, the implementation of various post-launch tests has been delayed, resulting in the postponement of its commissioning. What factors account for this delay? Broadly speaking, they can be divided into two categories: Factors related to project management and those associated with Taiwan’s domestic political divisions.

With regard to project management, one issue that has been highlighted is delays in the delivery of equipment systems to be installed on Hai Kun.[13] For example, it has been pointed out that delays in the procurement of the optronic mast manufactured by US company L3Harris postponed the commencement of sea trials.[14] This can likely be attributed to the large number of foreign suppliers involved, which has rendered the supply chain for Hai Kun increasingly complex. While the large number of foreign contractors involved can be seen as evidence of multinational cooperation in Taiwan’s submarine construction efforts, it may also be regarded as a factor impeding commissioning. Moreover, reports of internal disputes between naval advisers involved in the Hai Kun construction project and participating contractors,[15] as well as incidents of information leakage during the construction process,[16] suggest that adequate control was not fully maintained throughout the construction and operational processes.

As for political factors in Taiwan, one issue is the opposition parties’ lack of enthusiasm for the indigenous submarine construction program. Following the 2024 presidential and Legislative Yuan elections, opposition parties such as the Kuomintang hold a majority in the Legislative Yuan. The opposition has advocated budget reductions and froze approximately 10 billion NTD (about ¥50 billion)—roughly half of the funding related to indigenous submarine construction—in the 2025 budget proposal submitted by the Executive Yuan.[17] The opposition camp’s argument is that, given the low feasibility of enabling future mass production of submarines, funding should be frozen until Hai Kun completes its testing.[18] However, this stance may be affecting not only the construction of follow-on submarines but also various processes required for Hai Kun’s commissioning. From a political perspective, another relevant factor is that Huang Shu-kuang, who had been a driving force behind the indigenous submarine program, resigned in September 2025 from his positions as an adviser to the National Security Council and as leader of the indigenous submarine construction project team housed within the Presidential Office, citing “family reasons.”[19]

4. Security Implications of Hai Kun’s Delayed Deployment

Delays in Hai Kun’s commissioning will inevitably lead to delays in the construction of follow-on indigenous submarines and, in turn, to stagnation in the development of Taiwan’s submarine force. Such delays could also undermine efforts to enhance countermeasures against potential Chinese maritime blockades and amphibious operations.

However, the impact of Hai Kun’s delayed commissioning on Taiwan’s security extends beyond the mere development of military capabilities. Such delays risk heightening skepticism, both domestically and internationally, regarding Taiwan’s capacity to build its defense capabilities autonomously. Perhaps with the intention of amplifying such doubts, unconfirmed information concerning Hai Kun’s delayed deployment has already begun to circulate. For example, the Taiwanese online media outlet Mirror News reported an “exposé” in November 2025, alleging that Hai Kun was not equipped with an anchor during its sea trials, thereby endangering the lives of its crew and violating maritime law.[20]

In addition, cybersecurity experts have pointed out that a post on Weibo, a Chinese social media platform, claiming that Hai Kun’s hull was deformed after a five-hour test voyage was subsequently disseminated on social networking services widely used in Taiwan, such as Threads and X. This case suggests the possibility of Chinese involvement.[21]

Furthermore, China’s state-affiliated English-language media outlet Global Times cited the aforementioned reports by Taiwanese media alleging that Hai Kun lacked an anchor, among other claims, and published articles asserting that these reports “exposed the vulnerabilities of Taiwan’s submarine,”[22] thereby criticizing Hai Kun’s operation. Moreover, a spokesperson for China’s Ministry of National Defense stated in October 2025 that “the DPP authorities are squandering the hard-earned money of the Taiwanese people in pursuit of ‘independence through force’” and that the “‘indigenously built’ submarine would not be able to withstand even a single blow from the People’s Liberation Army.”[23] As such, a certain degree of overlap can be observed between information circulating within Taiwan and narratives disseminated by the Chinese side.

Taiwanese authorities are also aware of these dynamics. In a report submitted to the Legislative Yuan, the Political Warfare Bureau of Taiwan’s Ministry of National Defense stated that Hai Kun has become a key target of China’s information warfare, noting that a total of 22,407 pieces of related unconfirmed information have been identified. According to the report, such information can be classified into five categories: (1) wasteful spending, (2) technical deficiencies, (3) its use as a tool of political propaganda (by the Taiwanese government), (4) low operational value in actual combat, and (5) the limited proportion of domestically produced components. The bureau further pointed out that all of these narratives are intended to weaken defense awareness within Taiwanese society.[24]

China may not be responsible for all of the negative information circulating about Hai Kun. Nevertheless, given China’s consistent criticism of Taiwan’s efforts to strengthen its defense capabilities, as well as the fact that Chinese media have mounted critical campaigns drawing on information circulating within Taiwan, it is plausible that Beijing is exploiting the existence of critical discourse in Taiwan regarding the construction of indigenous submarines, including Hai Kun, to shape a narrative that “Taiwan lacks the capability to build submarines and, by extension, to develop autonomous defense capabilities, making such efforts futile.”

Conclusion

Submarines have long been regarded as critical assets for countering enemy maritime blockades and amphibious assaults, as was the case in the early years of the People’s Republic of China[25] when it perceived significant military threats from the United States. In this sense, it is rational for Taiwan—recognizing the possibility of similar risks in the future—to pursue the indigenous construction of submarines. If Taiwan’s assertion that criticism of Hai Kun’s operation has become a focal point of China’s cognitive warfare is taken into account, it may also suggest that China perceives Taiwan’s submarines as a significant threat.

On the other hand, Taiwan has procured a wide range of technologies and equipment from overseas because Taiwan lacked indigenous know-how in submarine construction. While this can be viewed politically as the manifestation of an international support framework for Taiwan, it has also complicated the supply chain and become a factor contributing to Hai Kun’s delayed commissioning. Taken together, these factors suggest that insufficient project management by the Taiwanese government and CSBC has underpinned the failure to achieve the goal of commissioning. Moreover, the intensification of domestic political confrontation in Taiwan in recent years has further exacerbated this situation.

There are also views that point to fundamental problems with Taiwan’s submarine construction program itself while not denying the value of possessing submarines per se: namely, that a target fleet size of eight submarines is insufficient to counter China, that the projected completion date of 2038 is too distant, and that the submarines lack features that are standard on modern advanced platforms, such as air-independent propulsion (AIP) systems and the use of sound-absorbing materials.[26] Furthermore, even taking into account that Hai Kun is Taiwan’s first indigenous submarine and that its development has entailed enormous costs, its construction cost remains significantly higher than that of Japanese submarines. This raises the need to consider budgetary balance with other, more affordable and flexible capabilities that Taiwan is pursuing in parallel, such as small corvettes, minelayers, and unmanned water vehicles.

These lines of argument bear certain similarities to the critical narratives directed at Taiwan’s indigenous submarine program within the context of cognitive warfare in which China is also involved. However, dismissing all such criticisms generally as “cognitive warfare” risks instead exacerbating societal divisions and expanding opportunities for China to exploit them. Accordingly, while Taiwan faces an urgent need to strengthen its defense capabilities—including submarines—amid China’s rapid military buildup, the Taiwanese government must also listen to such critiques and respond to them in an appropriate and measured manner. Fundamentally, there are numerous factors that must be taken into account, including the selection of technology and equipment suppliers, schedule management, and the appropriateness of budget allocations. Moreover, how the United States—Taiwan’s principal security partner—formulates its guidance on strengthening Taiwan’s defense capabilities constitutes another variable, which will inevitably affect the construction and operation of indigenous submarines. In this sense, the development of Taiwan’s indigenous submarines, including Hai Kun, can be seen as encapsulating the challenges inherent in Taiwan’s efforts to enhance its autonomous defense capabilities.

(* All titles and positions are as of the time referenced. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author and do not represent the views of the author’s affiliated institution.)

1 In this paper, unless otherwise noted, “China” refers to the People’s Republic of China, established in October 1949, and “Taiwan” refers to the Republic of China, which exercises effective control over the island of Taiwan and its surrounding islands.

2 For Taiwan’s efforts to strengthen its maritime capabilities and the underlying military thinking behind them, see also Yohei Goto, “ROC Navy’s Military Strategy against China: Its Threat Perception and Procurements,” Ships of the World, No. 1048 (September 2025).

3 Seth Gropsey, “Taiwan Needs Submarines to Defend itself” (Hudson Institute, Washington, D.C., October 2022). [https://www.hudson.org/national-security-defense/taiwan-needs-submarines-to-defend-itself]

4 Statement by Huang Shu-kuang, former Chief of the General Staff (former Navy admiral second class), who led the submarine construction project team under the Tsai Ing-wen administration (2016–2024), Liberty Times, September 26, 2023. [https://news.ltn.com.tw/news/politics/paper/1606745]

5 Republic of China’s National Defense Report Editorial Committee, “National Defense Report 2025” (Ministry of National Defense, October 2025), p. 127.

6 The following account of Taiwan’s pursuit of indigenization draws on Chung Chieh, “The Story of the Indigenous Submarine Program That Should Not Be Forgotten,” Pen Teng Ssu Chao (Le Penseur), October 23, 2023. [https://www.lepenseur.com.tw/article/1546]

7 Zachary Keck, “US to Help Taiwan Build Attack Submarines,” The Diplomat , April 15, 2014. [https://thediplomat.com/2014/04/us-to-help-taiwan-build-attack-submarines/]

8 Unless otherwise noted, the content of section “2,” including the table below, is based on BBC’s Chinese version, June 30, 2025. [https://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/articles/cpqnnddw9jdo/trad]

9 Brandon J. Weichert, “Taiwan’s Hai Kun Diesel-Electric Submarine Could Deter China. Here’s Why It won’t,” The National Interest, February 27, 2025. [https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/taiwans-hai-kun-diesel-electric-submarine-could-deter-china-heres-why-it-wont]

10 Reuters, November 29, 2021. [https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/taiwan-china-submarines/]

11 Kosuke Takahashi, “Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force’s latest 3,000-ton-class submarine Taigei launched—named after Taigei, a submarine tender of the defunct Imperial Japanese Navy,” Yahoo News, October 14, 2020. [https://news.yahoo.co.jp/expert/articles/ca12f4df69c9aa752fc535b444b26de58285d0ec]

12 Electronic version of Nihon Keizai Shimbun, March 6, 2025. [https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXZQOUF0562A0V00C25A3000000/]

13 BBC’s Chinese version, June 30, 2025.

14 Naval News, May 2024. https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2024/05/taiwans-new-submarine-ready-for-sea-trials-following-delayed-optronic-mast-delivery/

15 Kevin Ting-chen Sun, “Lessons from Taiwan’s Submarine Woes,” National Interest, November 2, 2025. [https://nationalinterest.org/feature/lessons-from-taiwans-submarine-woes]

16 Holmes Liao, “Taiwan’s Submarines at a Crossroads,” National Defense, November 7, 2025. [https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2025/11/7/commentary-taiwans-submarines-at-a-crossroads]

17 Sankei Shimbun news, January 22, 2025. [https://www.sankei.com/article/20250122-2RSTRFAHFJPABOJI5YF7RXI6D4/]

18 BBC’s Chinese version, June 30, 2025.

19 Liao, “Taiwan’s Submarines at a Crossroads”.

20 Mirror News, November 29, 2025, [https://www.mirrordaily.news/story/32200]. It should be noted that Mirror News seems to be a media outlet distinct from Mirror Media, a Taiwanese media organization established in 2016, and appears to rely frequently on externally sourced “exposés” for its reporting. On the same day, CSBC Corporation, Taiwan—the principal contractor for Hai Kun—issued a statement asserting that there are means other than an anchor to ensure crew safety and that, pursuant to Article 4 of the Ship Act, vessels intended for military use are exempt from the application of the law. (Storm Media, November 29, 2025, [https://www.storm.mg/article/11084566]). It should also be noted that Mirror News reported on December 21 another “exposé” alleging that Hai Kun was conducting tests under “minimum safety standards” at the direction of Navy headquarters, a claim that CSBC again denied. (Mirror News, December 21, 2025, [https://www.mirrordaily.news/story/35957; Liberty Times, December 21, 2025; https://news.ltn.com.tw/news/politics/breakingnews/5285355]).

21 China Times, June 22, 2025. [https://www.chinatimes.com/realtimenews/20250622002206-260407?chdtv]

22 Global Times, December 2, 2025. [https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202512/1349482.shtml]

23 China’s Ministry of National Defense website, October 10, 2025. [http://www.mod.gov.cn/gfbw/xwfyr/yzxwfb/16414391.html]

24 Central News Agency, November 10, 2025. [https://www.cna.com.tw/news/aipl/202511100151.aspx]

25 In its early years, China placed emphasis on submarine development in order to counter maritime blockades by the United States, and achieved indigenous submarine construction in the 1960s. See Toshihide Yamauchi, “The Development of Submarine Forces,” in Ryo Asano and Toshihide Yamauchi (eds.), “China’s Maritime Power: The Navy, Merchant Fleet, and Shipbuilding—Its Strategy and Development” (Soudosha, 2014), pp. 222–227.

26 Weichert, “Taiwan’s Hai Kun Diesel-Electric Submarine Could Deter China”.