Contents *Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited

SPF China Observer

HOMENo.47 2024/01/19

The possible further cooperation between the Coast Guard of Japan and Taiwan

1. Background

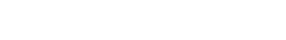

Japan and Taiwan are both considered "maritime nations." Despite differing territorial boundaries and claims, they engaged in negotiations leading to the signing of the Taiwan-Japan Fisheries Agreement.[1] This accord facilitated mutual benefits at sea, establishing three areas for mutual recognition or exclusion of laws. These measures allowed fishers from both sides to conduct economic activities in the region. Moreover, the agreement authorises the Coast Guards and other related organisationsof the two to establish a mechanism to manage maritime security and order following relevant laws and regulations.

In 2017 and 2018, Japan and Taiwan solidified their maritime cooperation based on the above by signing two memorandums of understanding: the Taiwan-Japan Search And Rescue Cooperation MoU (hereafter SAR)[2] and the Anti-Smuggling and Customs Cooperation MoU.[3] These agreements aimed to strengthen safety and security collaboration despite the absence of official diplomatic ties.

https://shorturl.at/jnrCE

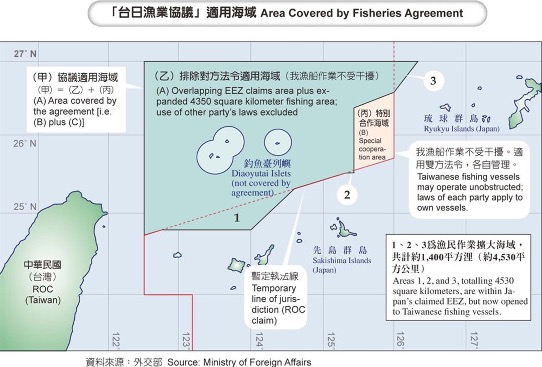

However, despite the expressed willingness to cooperate and sign agreements, there remains room for improvement in actual cooperation at the grassroots level. The waters surrounding Japan and Taiwan are busy and rich in fishing resources brought by Kuroshio and Oyashio. The complex currents and sea conditions necessitate frequent search and rescue operations by both Coast Guards, totaling over 1,000 cases annually.[4]

Although both nations have overlapping Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) and signed MoUs indicating cooperation intentions, large-scale joint training and exercises are notably absent. Especially in SAR and Customs Cooperations, which involve personnel safety and maritime law enforcement, require closer cooperation and coordination of both parties. Instead, there are only a few operational exchanges between the two. For example, the Taiwan Coast Guard sends officials to Naha as a liaison stationed in the Exchange Association; as well as Japan sends counterparts to Taipei.[5]

In contrast, the US-Taiwan "MoU on Cooperation of Coast Guard Working Groups" strengthens bilateral cooperation with exchange programmes and joint exercises in nearby waters in the areas including preserving maritime resources; reducing illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing (IUU); and participating in joint maritime search and rescue as well as maritime environmental response events. Exchanging personal

https://shorturl.at/dmPV5E

and even joint training and exercises are held non-periodically.[6] Conversely, the content of the MoU between Taiwan and Japan has room for expansion, and the frameworks for cooperation and negotiation on SAR need improvement.

2. Challenges & Cooperations

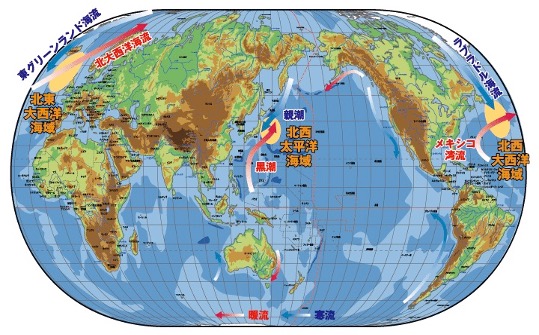

The maritime activities in the region present challenges, with bustling sea traffic and economic activities—both nations are located at seismic zones and natural disasters, making accidents a common occurrence. As mentioned above, there are a large number of fishing vessels engaged in maritime economic activities on the one hand, and on the other hand, there are also transportation and navigation vessels from all over the world which makes this area occupied. It is challenging for the maritime management and safety response to neighbouringcountries.

Another challenge is from the Chinese militia. China launched extensive scales of maritime militia, which to be called "grey zone operations", combining militia and coast guards, continue to exist in the disputed areas to create a fait accompli, and disrupt other countries’ maritime order for undermining that country’s claims to sovereignty.[7] Even if ignore the relationship between the Chinese government and its militia, the various illegal, IUU activities conducted by armed fishing boats still pose a large-scale threat to the fishery resources and seabed natural resources in the waters surrounding Taiwan and Japan.

Due to the IUU behaviour of these maritime militias and their refusal to cooperate with other countries' laws and regulations, those "fishing boats" at sea destroying the local natural resources and environment, and affecting the livelihood of local fishers.[8] Hence, even simple fishing at sea may cause conflicts due to competition for fish resources among countries. Currently, in order to avoid such accidents, both Taiwan and Japan are trying their best to monitor activities in the area in real-time using satellites and AIS system, or directly dispatch Coast Guards to the area to protect fishers.

According to the above perspectives, Taiwan and Japan have more to cooperate.

Firstly, in the safety aspect, namely SAR, the International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue, effective since 1985, obligates coastal nations to establish maritime affairs agencies and delineate responsibilities for sea areas[9]. Japan and Taiwan comply with this agreement, even though international organisations exclude Taiwan. However, despite two sides enjoying agreements and memoranda, joint training and exercises for SAR and Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) are lacking. Both sides’ Coast Guard have their own relevant units and regulations responsible for SAR and HADR. In special situations where a ship carrying hazardous cargo is in distress, sinking, experiencing a fire, or requires diving due to special circumstances, for example, a specialised team from Japan Coast Guard (hereafter JCG), known as the "special rescue team" takes charge.[10]

https://shorturl.at/fsBEW

Relatively, Taiwan's Coast Guard (hereafter TCG) has clearly defined responsibilities based on geographic areas. Each local division is equipped with "Coast Guard Units" responsible for routine security patrols and surveillance, as well as carrying out SAR operations during accidents.[11]

Despite the mutual agreements and memoranda signed by both sides, there is a notable absence of joint training and exercises. It remains uncertain whether both parties can seamlessly cooperate and collaborate for SAR and HADR without prior coordination. One significant challenge lies in the fact that Taiwan utilises the SAR system by participating in the US programme AMVER[12], while Japan operates its system known as the Japanese Ship Reporting System (JASREP). Although Japan has established an exchange mechanism to accommodate the differences between the two systems, the question of whether Taiwan can effectively coordinate with it still remains questioned.

Besides, the vulnerability lies in the fact that AIS's spoofing has been considered feasible in actual cases. China's energy transport ships use AIS spoofing[13] to circumvent global sanctions against Russia, which makes the monitoring mechanism through AIS appear to be vulnerable.[14] Therefore, if a large number of fishing boats from China use AIS spoofing, it will be difficult for Taiwan and Japan to grasp real-time information through the system in the first place. It can be seen from the above cases that even if the on-site situation can be grasped, it may already be some time later. For the monitoring of regional security, it is nothing more than a challenge and threat.

Moreover, in the event of unforeseen accidents, such as the 2011 incident when a North Korean spy ship intruded into the surrounding waters, Taiwan and Japan coordinating their response through established training, doctrines, and communication mechanisms becomes crucial in determining whether the action succeeds or fails. In practical terms, both parties must identify, apprehend, or take forceful action against unidentified third-party vessels. If the actions of both parties lack consistency, it not only allows the target to escape amidst the chaos but may also result in injuries and damage to front-line personnel and equipment.

Currently, the on-site communication mechanisms between Japan and Taiwan, rely solely on broadcasting using a Very High Frequency (VHF) communication system, according to the regulations of the International Maritime Organization (IMO). However, the broadcasting channel is not a closed one, meaning that third parties in the area could also monitor and intercept the communication, potentially complicating response efforts. The current practice is that the two parties actually conduct necessary communication on-site through VHF. However, a persistent challenge looms in the form of communication interception and disruption by Chinese vessels, be they public ships or part of the militia. This poses a substantial barrier to the seamless implementation of maritime security cooperation between Taiwan and Japan.

3. Defining Actions and Clarify the Responses

Due to the dynamic nature of maritime security challenges, ordinary disputes in the open sea can escalate into intense conflicts, potentially leading to diplomatic disputes between nations involved. In 2016, a law enforcement incident between Taiwan and the Philippines resulted in a tragic confrontation. The Philippine Coast Guard, acting unprofessionally, fired at a Taiwanese fishing vessel engaged in illegal fishing, bypassing proper law enforcement procedures and causing casualties among Taiwanese fishers. This incident led to a significant diplomatic conflict, which concluded with the arrest and sentencing of relevant personnel in the Philippines.[15]

For both Taiwanese and Japanese coastguards, the frontline approach while handling crises is minimising conflicts and tension as much as possible. However, this approach is designed to address general instances of illegal activities. If maritime militias or fishing vessels deliberately ignore legal principles, purposefully challenge the enforcement authority of Taiwan and Japan, or engage in intentional collisions with vessels, persisting with the aforementioned approach could potentially cause irreversible harm to frontline law enforcement personnel or trigger larger conflicts. This is particularly concerning given that many Chinese fishing vessels currently utilise modified iron-hulled ships, posing a significant safety threat when colliding with the lighter metal-hulled law enforcement vessels of Taiwan and Japan.

Currently, Japan's practice, when facing challenging situations that the Japan Coast Guard finds difficult to handle, is to request the Self Defence Forces for "maritime security operation(海警行動)." Despite the identity being "SDF," according to the Japan SDF Law, they are considered police and must adhere to relevant regulations under the Police Duties Execution Act. On the other hand, when the Prime Minister deems it necessary, the command authority of the Japan Coast Guard can be transferred to the SDF until the crisis is resolved.[16] This legal authorisation provides flexibility and comprehensive utilisation in responding to maritime security challenges, especially those originating from non-military entities or actions, and avoids situations escalating into uncontrollable conflicts.

As for Taiwan, the "Coordination and Liaison Measures between the Taiwan Coast Guard and the Navy" were established in 2001 and have been continuously revised and improved thereafter. Between the Taiwan Coast Guard and the Navy, both sides can request support from each other as needed for mission execution, and they can exchange safety information and intelligence through various means.[17] However, compared to Japan, Taiwan does not have specific regulations regarding the use of force by the Navy in supporting the Coast Guard. Therefore, in this aspect, Taiwan adopts a blurred approach.[18]

Whether in Taiwan or Japan, in this kind of joint operation combining different services, it is not a problem to clearly identify the ships of Coast Guard or Navy. But for transnational operations, it is very important to be able to identify the identity at sea. Although both Taiwan and Japan use the American series equipment, the electronic parameters of different equipment are different, which will lead to different results on the radar display. Clarifying the identification of friend and foe, as well as "unknown third parties", is crucial for the execution of operations and safety cooperation. This clear identification is especially necessary during SAR or HADR operations.

4. Conclusion

The communication mechanism is the fundamental element in building mutual confidence and implementing crisis control and management measures. Despite China's attempts to forcibly conquer Taiwan and deploy militia against it, both parties have established maritime communication channels to jointly manage the waters surrounding Kinmen and Matsu. These channels cover vessels from both sides and aim to prevent crises. Additionally, joint search and rescue exercises between China and Taiwan in the aforementioned waters took place a decade ago.[19]

Presently, Taiwan and Japan have set aside territorial disputes, exemplifying a friendly relationship through actions such as sharing fishing rights, which safeguards the rights of fishers on both sides. However, for effective joint or cooperative operations, including SAR, HADR, and enforcement of ordinances, there is a need for good communication and consistency of action between the two sides. This requires maintaining consistency in legal frameworks and operational principles. Regardless, this paper emphasises the importance for both Taiwan and Japan to promptly establish:

- A mechanism or system for clear identification of both parties.

- A confidential communication channel during frontline mission execution.

- Swift establishment of joint training and exercise mechanisms for SAR and HADR.

By doing so, it will further ensure the personal safety and crisis management of fishers and individuals engaged in economic activities or maritime navigation in the surrounding waters.

The United States, Australia, Japan, and Taiwan established a cooperation framework in 2015 known as the "Global Cooperation & Training Framework (GCTF)."[20] While this framework is a positive step for global cooperation with Taiwan, it primarily focuses on international humanitarian assistance, public health, environmental protection, energy, science and technology, education, and regional development. Unfortunately, maritime safety and security cooperation are notably absent from its scope. Therefore, it is imperative to underscore the significance of maritime security cooperation.

Given the shared values and security concerns between Taiwan and Japan, strengthening cooperation in this area becomes even more necessary. The paper aims to emphasise the critical role of maritime security and advocate for its inclusion in the existing framework.

Despite an unfortunate and tragic accident that occurred years ago, the Philippines and Taiwan continue to conduct joint maritime science research operations and cooperate against China's harassment. This is understandable as communication and operational mechanisms aim to protect and save lives, irrespective of the nations' relationship. In the South, it involves Taiwan and the Philippines, while in the North, it's between Taiwan and Japan. Ongoing communication to establish crisis management procedures between Taiwan and the Philippines makes it challenging to comprehend any reasons for Japan and Taiwan not to do the same.

In order to save lives, manage crises, distinguish between friend and foe, and prevent unpredictable accidents, it would be wise for both Japan and Taiwan to establish a communication channel and conduct joint SAR and HADR exercises at the earliest stage possible.

Lastly, China escalates its challenges regarding territorial disputes in the South China Sea and East China Sea, using excuses like natural disasters or shipwrecks to station a large number of fishing boats. If such incidents were to occur around the Uotsuri Jima, Minami, or Kita Kojima, it might pose additional challenges for both Taiwan and Japan, which is also worth noting.

1 Japan-Taiwan Exchange Association, “The agreement was officially between the Interchange Association of Japan and Taiwan’s Association of East Asian Relations,” April 4, 2013.

https://www.koryu.or.jp/Portals/0/images/news/20130410/20130410torikime.pdf

2 Japan-Taiwan Exchange Association, “Memorandum of Cooperation in the field of maritime search and rescue between the Interchange Association of Japan and Taiwan’s Association of East Asian Relations,” December 20, 2017.

https://www.koryu.or.jp/Portals/0/tokyo/MOU/20171220_0001.pdf

3 Japan-Taiwan Exchange Association, “Memorandum of Cooperation in the field of maritime search and rescue between the Interchange Association of Japan and Taiwan’s Association of East Asian Relations,” December 27, 2018.

https://www.koryu.or.jp/Portals/0/tokyo/MOU/20181227%EF%BC%88%E5%AF%86%E8%BC%B8%E5%AF%86%E8%88%AA%EF%BC%89_0001.pdf

4 According to the statistics from year 2010 to 2021, the total rescue and life saving cases of Taiwan are over 1,000 annually, only three years below the number. See :Coast Guard Administration, Ocean Affairs Council,‘Disaster Rescues and Service Works —by Month,’ “2021 Coast Guard Annual Statistical Report,” https://www.cga.gov.tw/GipOpen/wSite/np?ctNode=2461&mp=eng

The statistics in Japan is also around the numbers. See : Japan Coast Guard,‘Survey by type of marine accident requiring rescue,’“Maritime Security Statistics Annual Report, ” https://www.kaiho.mlit.go.jp/doc/hakkou/toukei/toukei.html

5 Madoka Fukuda, “Taiwan Maritime Security Policy Country‧Profile,” ‘Research Report on Rule of Law Issues and Maritime Security in the Indo-Pacific ‘Country Profile’,’ JIIA, 2016, p. 9. https://www2.jiia.or.jp/pdf/research/H28_Indo-Pacific_country_profile/11-fukuda.pdf

6 “U.S.-TAIWAN COAST GUARD WORKING GROUP ADVANCES JOINT MARITIME COOPERATION GOALS,” AIT, 11 August, 2021. https://www.ait.org.tw/us-tw-cgwg-advances-joint-maritime-cooperation-goals/

7 Samir Puri, Greg Austin, "What the Whitsun Reef incident tells us about China’s future operations at sea," IISS, April 9, 2021.https://www.iiss.org/online-analysis/online-analysis//2021/04/whitsun-reef-incident-china

8 Commander Jennifer Runion, "Fishing for Trouble: Chinese IUU Fishing and the Risk of Escalation," US Naval Institute, February 2023.

https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2023/february/fishing-trouble-chinese-iuu-fishing-and-risk-escalation

9 "International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue (SAR)," International Maritime Organisation, Adoption: 27 April 1979; Entry into force, 22 June 1985.

https://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/Pages/International-Convention-on-Maritime-Search-and-Rescue-(SAR).aspx

10 Japan Coast Guard, “About the Japan Coast Guard emergency rescue system,” December 4, 2015.

https://shorturl.at/oFHO6

11 Ocean Affairs Council, “Organization of Central Branch,” Central Branch Coast Guard Administration.

https://www.cga.gov.tw/GipOpen/wSite/ct?xItem=20756&ctNode=6767&mp=9993

12 Ship Location Reporting System Sponsored by the U.S. Coast Guard https://www.amver.com/

13 See, “Automatic Identification System Spoofing,” OSIANA. https://usa.oceana.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2023/07/AIS-Spoofing-Factsheet.pdf

14 Christiaan Tribert, Blacki Migliozzi, Alexander Cardia, Muyi Xiao, and David Botti, "Fake Signals and American Insurance: How a Dark Fleet Moves Russian Oil," The New Yorks Times, May 30, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/05/30/world/asia/russia-oil-ships-sanctions.html

15 See the case in: "Taiwan imposes sanctions on Philippines over killing," Reuters, May 15, 2013. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-taiwan-philippines/taiwan-imposes-sanctions-on-philippines-over-killing-idUSBRE94E0N020130515/

16 Article 80 regulates the relationship with the Coast Guard, and Article 82 deals with regulations such as maritime security operations. See:“Self-Defense Forces Law,”e-Gov Law search.https://elaws.e-gov.go.jp/document?lawid=329AC0000000165

17 “Regulations Governing Coordination & Liaison between Coast Guard Administration and Ministry of National Defense,” The Laws & Regulations Database of the Republic of China.

https://law.moj.gov.tw/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?pcode=D0090025

18 However, here must to emphasised that, the Taiwan Coast Guard and Navy have a close training relationship. Not only does the Coast Guard have military personnel, but the two agencies have joint training courses for officers. See Hsin-Yao Huang,“Liu Chih-Pin inspected the maritime patrol unit to express his condolences to the trainees for their hard work,” Youth Daily News, March 26, 2022.

https://www.ydn.com.tw/news/newsInsidePage?chapterID=1492455&type=military

19 Cross-Strait joint maritime search and rescue training, small three links to establish rescue mechanism ,” Matsu Daily News, September 18, 2010. https://www.matsu-news.gov.tw/news/article/151114 Worth emphasising is, despite the framework is exists, however, whether to conduct drills often depends on China's political judgment; especially when the Democratic Progressive Party is in power, such drills are often hindered or even interrupted.

20 Japan-Taiwan Exchange Association, “Global Cooperation and Training Framework (GCTF).” https://www.koryu.or.jp/en/business/gctf/