Contents *Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited

SPF China Observer

HOMENo.42 2023/04/04

Signs of China’s Resumption of Nuclear Tests: Strong Determination to Bolster Nuclear Force and the Crisis of Nuclear Proliferation

Yuki Kobayashi (Research Fellow, Sasakawa Peace Foundation)

1.China’s Nuclear Arms Expansion and Its Impact

China is seriously expanding its nuclear armament in its attempt to achieve nuclear power balance with the U.S. The 2020 edition of the annual report on military trends in China submitted by the U.S. Department of Defense to Congress pointed out that, “Over the next decade, China’s nuclear warhead stockpile — currently estimated to be in the low-200s — is projected to at least double in size.”[1] The 2021 edition predicted that “the PRC likely intends to have at least 1,000 warheads by 2030,”[2] and the 2022 edition raised its estimate significantly, claiming China “will likely field a stockpile of about 1,500 warheads by its 2035 timeline.”[3]

One reason cited for the U.S.’s upward revision of its estimates and openly voicing its concern about China’s nuclear arms expansion is that China has increased its production of plutonium for civilian use (power generation) and is suspected of secretly converting this for military purposes, as pointed out in my previous article “Observations on Lack of Transparency in China’s Nuclear Arms Expansion: Ahead of the NPT Review Conference.” China has been building nuclear fuel reprocessing facilities that can extract plutonium from spent fuel from nuclear power plants and fast breeder reactors that can extract weapon-class ultrapure plutonium through nuclear reaction in the reactors. There is an analysis that both these facilities will start operation shortly. In addition, China is also accelerating its development of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM) and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBM) as delivery vehicles for nuclear warheads.

On top of these developments, there have been signs of China’s resuming its nuclear tests as a manifestation of its strong determination to expand nuclear armament.

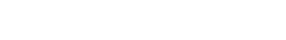

Satellite images obtained by Sasakawa Peace Foundation’s China Observer show that new equipment have been transported to the Lop Nur Nuclear Test Site in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (See Diagram 1), where China used to conduct many of its nuclear tests, and tunnel digging necessary for underground nuclear tests and the construction of related facilities are in progress. An analysis of these images points to the possibility of nuclear tests taking place in the near future.

Diagram 1: Lop Nur Nuclear Test Site

China’s lack of transparency in its increased plutonium production and signs of resumption of nuclear tests will not only heighten U.S.-China tension and tension in the Asian region, but may also bring about the collapse of the nuclear order centered on the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). While China has not ratified the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), which bans nuclear tests that come with explosions,[4] it has signed the treaty and has declared its compliance with it repeatedly.[5] As a matter of fact, it has not conducted any nuclear tests involving explosions since 1996. Therefore, it is reckoned that there is a strong possibility that China is renovating the Lop Nur site in preparation for subcritical nuclear tests with no explosions that do not violate the CTBT. However, even short of violating the CTBT, China’s revelation of its determination to expand nuclear armament means that its nuclear force may become a threat to other countries and trigger nuclear arms expansion and proliferation on a global scale.

This article will first analyze the satellite images of the Lop Nur Nuclear Test Site and offer observations on China’s intent regarding nuclear tests. It will also discuss the impact of China’s nuclear arms expansion on the neighboring countries and the international community, as well as what role Japan must play to mitigate this impact.

2.Developments at the Lop Nur Test Site and China’s Goals

(1) History of the Lop Nur Test Site

Before going into the analysis of satellite images of the Lop Nur Nuclear Test Site, this article will offer an overview of the underground nuclear test procedures and a history of the Lop Nur site.

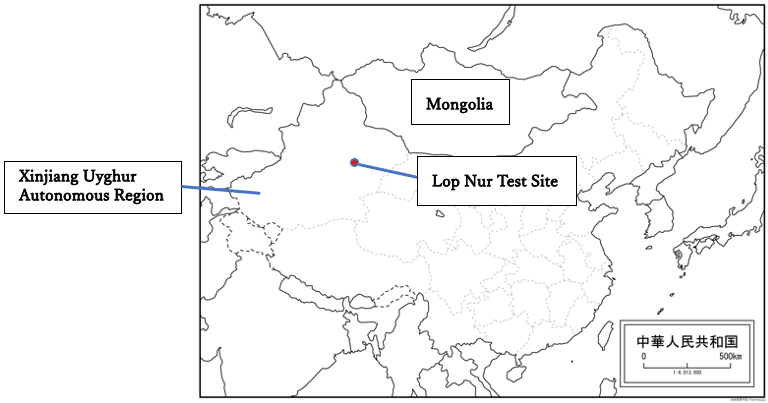

Diagram 2: Basic Structure and Procedures of Nuclear Test Sites

Underground nuclear test sites involve digging tunnels through the mountain in many cases. The simplified diagram above shows a horizontal tunnel, but according to Secretary General Tomonori Iwamoto of the Institute of Nuclear Materials Management Japan Chapter, tunnels are bent on the way and dug deeper for placing the nuclear bomb inside in case the explosion is unexpectedly powerful. Since electric signals are sent to detonate the nuclear bomb, massive cables are laid into the tunnel. In addition, to prevent large-scale leak of radioactive substances outside the tunnel, the entrance is covered with a thick steel wall and an earthen wall. A control tower is also located near the tunnel to oversee the experiment and monitor the intensity of the explosion and changes in physical properties of the nuclear substances.

It is estimated that 46 nuclear experiments with explosions had taken place at the Lop Nur test site after the first nuclear test above ground was conducted in October 1964. (See Table 1) Although the U.S., the UK, and the Soviet Union signed the Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) prohibiting nuclear tests in the atmosphere in August 1963, China, which was lagging behind in nuclear arms development, did not accede to this treaty. It conducted repeated aboveground nuclear tests at the Lop Nur site until the 1980s. Subsequently, it shifted to underground nuclear tests and has built a total of five tunnels so far. The last nuclear test with explosion took place there in July 1996.[6]

Table 1: Nuclear Tests Conducted by the Nuclear Powers

| Country (Main Test Site) | Times | Above/underground |

|---|---|---|

| U.S. (Nevada Nuclear Test Site) | 1,030 | 215/815 |

| Russia (Semipalatinsk Test Site, former USSR; present day Kazakhstan) | 715 | 219/496 |

| France (Moruroa Atoll, South Pacific) | 210 | 50/160 |

| China (Lop Nur Nuclear Test Site) | 46 | 22/24 |

| UK (Maralinga Atomic Test Site, Australia) | 45 | 21/24 |

| North Korea (Punggye-ri Nuclear Test Site) | 6 | 0/6 |

| India (Pokhran, Thar Desert) | 3 | 0/3 |

| Pakistan (Ras Koh Hills) | 2 | 0/2 |

(2) China’s Intent in Renovating the Lop Nur Test Site: Possible Goal is to Conduct Subcritical Nuclear Tests

China’s intent becomes clear through an analysis of the satellite image below based on the setup of nuclear test sites and the history of the Lop Nur Test Site.

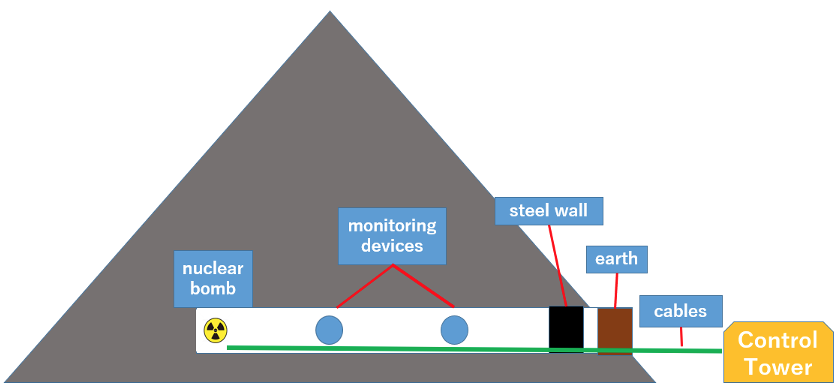

Image 1: Renovation of Lop Nur Nuclear Test Site

In this image taken in August 2022, a large artificial cover can be seen in the area marked with a red line. A line extending from the area close to this cover to the mountain is believed to be the tunnel. Considering the tunnel’s entrance is covered by steel plates and an earthen wall, as explained in Diagram 2, it is possible that the digging of a sixth tunnel in Lop Nur is underway. The left side of this photo clearly shows the endpoint of the tunnel digging. Although it is not possible to determine at this point whether a site for setting nuclear bombs will be built nearby, the fact that a very long tunnel has been dug along the mountain’s terrain with bends on the way indicates that the construction of the test site is in its final phase.

What is noteworthy is that there is a tall stack, whose shadow can clearly be seen, near the entrance of the tunnel (marked with orange line). Discerning what this stack means is indispensable for an accurate understanding of China’s intent.

One possibility is that this is being used for effective ventilation to ensure the safety of tunnel construction workers. Yet it is doubtful whether such a tall stack is necessary for tunnel ventilation. Iwamoto pointed to another possibility: this stack is to be used to release radioactive noble gas since China’s goal is to conduct repeated subcritical nuclear tests.

The main purpose of subcritical nuclear tests is to observe changes in physical properties of nuclear substances (plutonium) by applying shock waves with detonation devices and high-power lasers. The results are used as basic data for computer simulation to measure the power of nuclear explosions. The experiment ends before nuclear substances achieve criticality, which is the phenomenon in which sustained nuclear fission occurs, generating heat and radioactive substances. In nuclear power generation, criticality is achieved gradually to generate heat continuously for power generation, while in nuclear weapons, criticality is produced instantaneously, setting off explosions that come with flares, heat, and blasts.[7] Therefore, there would have been no need to build a massive underground facility to conduct subcritical nuclear tests that do not involve explosions.

However, the risk of failure to control criticality still exists, which may lead to explosions. Therefore, even subcritical nuclear tests at the Nevada Test Site in the U.S., which has much more advanced subcritical nuclear test technology, are conducted in underground facilities. It is reckoned that China acquired its subcritical nuclear test technology through the 46 nuclear tests with explosions it conducted so far. The sixth tunnel at the Lop Nur test site is being built to conduct repeated subcritical nuclear tests, and there is a strong possibility that the stack in question is meant to release radioactive noble gas into the atmosphere in case an explosion occurs.

3.China’s Strong Determination to Expand Nuclear Arms and Its Impact

(1) Effect of Subcritical Nuclear Tests on the Reinforcement of Nuclear Force

Subcritical nuclear tests may become a major means by which China achieves “military power balance” with the U.S. while suppressing criticism from the international community.

This is because they are not banned under the CTBT and are, in fact, taking place also in the U.S. and Russia. Furthermore, since no explosions are involved, they are not detectable by seismographs and other devices. Unless China makes announcements like the U.S., other countries will have no knowledge of its tests.

Subcritical nuclear tests also contribute significantly to the improvement of performance, including miniaturization, and to maintaining the quality of nuclear arms. The stable storage of nuclear weapons, which are extremely rarely used, not to say their miniaturization, is important for the nuclear powers. The purpose of nuclear tests is also to establish the technology for doing so. A U.S. inspector who was involved with the dismantling of nuclear weapons of the former Soviet Union after its disintegration testified that, “Nearly 60% of the nuclear weapons deployed by the USSR were duds. It is believed that the Soviet Union was impoverished before its disintegration, so it was unable to conduct sufficient nuclear tests and failed to maintain the stability of its nuclear arms.”[8] With continuous subcritical nuclear tests and the sophistication of the associated computer simulation, China will be able to overcome this problem.

Furthermore, China has also set up the systems for increasing production of plutonium, which is essential for making nuclear weapons. It has built nuclear fuel reprocessing facilities and fast breeder reactors scheduled to start operations by 2026. For those who are interested, this is discussed in detail in my previous article “Satellite Image Analysis: China’s Plutonium Production and Nuclear Arms Expansion.” From the above developments, the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center (NPEC), an organization of U.S. nuclear non-proliferation experts and former policymakers, estimates that China will possess 2.9±0.6 tons of weapon-class plutonium by the end of 2030. Assuming that one nuclear warhead requires 3.5±0.5 kilograms of plutonium, this amount translates into 830±210 warheads. The Pentagon’s analysis that “China may possess 1,000 nuclear warheads by 2030” cited earlier tallies with China’s projected increase in plutonium production. As can be seen in Table 2, this means that China is approaching the number of nuclear weapons deployed by the U.S. and Russia and will eventually catch up with them.

From the above, China is shifting from its policy of minimum deterrence, which is to possess the minimum retaliation capability to a nuclear attack that will ensure the destruction of the enemy’s major cities, and is now aiming at a “military power balance” that will ensure the destruction of the U.S., a major nuclear power.

Table 2: Number of Nuclear Warheads in the World (as of June 2021)

| Country | No. of warheads | No. deployed |

|---|---|---|

| Russia | 6,260 | 1,600 |

| U.S. | 5,550 | 1,800 |

| China | 350 | 0 |

| France | 290 | 280 |

| UK | 225 | 120 |

| Pakistan | 165 | 0 |

| India | 160 | 0 |

| Israel | 90 | 0 |

| North Korea | 40 | 0 |

| Total | 13,130 | 3,800 |

*Created by the author based on World’s Nuclear Warhead Data 2021, Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition, Nagasaki University.

(2) Global Impact of China’s Nuclear Arms Expansion

China’s nuclear arms expansion may have a serious impact on security and nuclear non-proliferation in the international community.

First, with a military power balance with the U.S., if China comes to judge that “mutual assured destruction” has been established with the U.S., it will assume that it can contain U.S. intervention in security issues in the Asian region. It is feared that as a result, it may resort to aggressive actions, including the unification of Taiwan and attempts to change the status quo by force.[9] To deter such actions by China, the U.S. may increase the operational deployment of its nuclear weapons. The U.S. possesses a large number of nuclear warheads other than those deployed for operations, which it can redeploy anytime. (See Table 2). However, many of these warheads are approaching their end of service life,[10] so it will have to take steps, such as conducting subcritical nuclear tests, to upgrade its weapons in order to compete with China. In which case, Russia will do the same. In light of the U.S.-Russia confrontation over the military invasion of Ukraine, it is highly possible that the only working arms control treaty between the two countries, the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START)[11] may be abrogated.

The impact will not be limited to the two major nuclear powers of U.S. and Russia. It is unthinkable that China’s neighbor India, which has a territorial dispute with China, will simply watch China expand its nuclear arms. It is reckoned that India will also embark on nuclear arms expansion, including the resumption of nuclear tests with explosions, which have been suspended since 1998. This will provoke neighboring Pakistan, thus extending the nuclear arms expansion to South Asia.

The wave of nuclear proliferation will also sweep Northeast Asia. If other countries resume nuclear experiments, North Korea may feel less inhibited to conduct its seventh and further nuclear tests. With North Korea conducting nuclear tests repeatedly, it is conceivable that the ROK may seek the redeployment of U.S. nuclear weapons the last of which were withdrawn in 1991 or the clamor for its own nuclear armament may gain momentum.

Japan will also be forced to respond. With China’s nuclear arms expansion in mind, the National Defense Strategy drawn up in late 2022 stated that “Japan needs to fundamentally reinforce its defense capabilities, with a focus on opponent capabilities and new ways of warfare.” It called for further strengthening the Japan-U.S. security alliance to enhance deterrence. It is possible that advocacy of “nuclear sharing”[12] with the U.S. may come up in this process.

The impact on the NPT regime will also be serious. Article 6 of the NPT mandates that the nuclear powers “undertake to pursue negotiations in good faith on …nuclear disarmament.” If the nuclear powers move toward nuclear arms expansion contrary to the wishes of the non-nuclear countries on compliance to Article 6, more countries will drop out from the NPT, and the international nuclear order based on this treaty will collapse.

4.Japan’s Response to China’s Nuclear Arms Expansion and Its Role

(1) Importance of Arms Control Treaties

Japan has declared that its national defense strategy is to work for strengthening deterrence with the U.S. and to “promote initiatives for arms control, disarmament, and non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction such as nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons in cooperation with relevant countries and international organizations.” In line with this policy, it should propose measures to maintain the credibility of the NPT regime. As a U.S. ally, it should call on the U.S. and Russia to maintain their arms control treaty, and as China’s neighbor, it should argue for the importance of such treaties. While in light of the current disparity in nuclear capability, it is not realistic for China to participate in the U.S.-Russia arms control treaty, China’s initiating discussions with the U.S. on arms control immediately will enhance the transparency of nuclear arms and contribute to improving the regional security environment. It is necessary for Japan to calmly call on China to understand that arousing suspicions in other countries and triggering a nuclear arms race and a nuclear proliferation domino effect through its nuclear arms expansion is not in its national interest.

(2) Utilization of Japan’s Nuclear Non-Proliferation Technology

As a more concrete contribution to the prevention of nuclear arms expansion in China and the world, it is also important to call for the introduction of the surveillance and other technologies developed by Japan to prevent the diversion of peaceful use of nuclear energy into the development of nuclear arms. Japan is the only non-nuclear country allowed to extract plutonium at nuclear fuel cycle facilities for reuse in fast breeder reactors. This is because, as the only atomic-bombed nation in the world, it has fully cooperated with the IAEA in handling nuclear substances that can be converted to military use and established the surveillance technology to prevent conversion of such substances for use as weapons. Such surveillance technology at nuclear fuel reprocessing facilities has been favorably cited by the U.S. Department of Energy, which stated that “recommending the installation of Japan’s surveillance technology should be considered for countries introducing nuclear fuel reprocessing in the future.”[13]

By calling for the introduction of the “Japan model” by nuclear powers not required to receive IAEA inspections, including China, and building up its initiatives to prevent the conversion of civilian technology for use as weapons in the future, Japan will enhance its credibility in the international community as a country promoting nuclear non-proliferation.

The Japanese government should exert utmost effort to lead the way to strengthening nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation, making full use of such technology as a diplomatic tool.

1 Office of the Secretary of Defense, “MILITARY AND SECURITY DEVELOPMENTS INVOLVING THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA 2020” [https://media.defense.gov/2020/Sep/01/2002488689/-1/-1/1/2020-DOD-CHINA-MILITARY-POWER-REPORT-FINAL.PDF]

2 Office of the Secretary of Defense, “MILITARY AND SECURITY DEVELOPMENTS INVOLVING THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA 2021” [https://media.defense.gov/2021/Nov/03/2002885874/-1/-1/0/2021-CMPR-FINAL.PDF]

3 Office of the Secretary of Defense, “MILITARY AND SECURITY DEVELOPMENTS INVOLVING THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA 2022” [https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/23321290/2022-military-and-security-developments-involving-the-peoples-republic-of-china.pdf]

4 The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) bans nuclear weapon test explosions in all spaces, including outer space, in the atmosphere, under water, and underground. The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO) was set up to verify compliance with the treaty, and verification methods were also stipulated to detect nuclear test explosions. However, tests without explosions (subcritical nuclear tests, etc.) are not covered by the CTBT ban, and this is regarded as a loophole for sophisticating nuclear arms and developing new weapons. See “Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT),” (in Japanese) Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (RECNA), Nagasaki University. [https://www.recna.nagasaki-u.ac.jp/recna/database/condensation/nucleartest]

5 Jonathan Landay, “U.S. says China may have conducted low-level nuclear test blasts,” Reuters, April 16, 2020. [https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-china-nuclear-idUSKCN21X386]

6 This paragraph is mostly based on “Nuclear Tests Conducted in East Turkestan,” (in Japanese) Japan Uyghur Association, May 13, 2015. [https://uyghur-j.org/japan/2013/05/%E6%9D%B1%E3%83%88%E3%83%AB%E3%82%AD%E3%82%B9%E3%82%BF%E3%83%B3%E3%81%A7%E8%A1%8C%E3%82%8F%E3%82%8C%E3%81%9F%E6%A0%B8%E5%AE%9F%E9%A8%93%E3%81%AB%E3%81%A4%E3%81%84%E3%81%A6/]

7 Explanation on subcritical nuclear tests and criticality based on author’s interview with Tomonori Iwamoto (Feb. 15, 2023) and Disarmament Dictionary (Gunshuku jiten), (in Japanese) Shinzansha, 2015.

8 Based on author’s interview with Iwamoto (Feb. 15, 2023)

9 Nobumasa Akiyama, Sugio Takahashi, End of Oblivion of Nuclear Arms: The Age of Reempowerment of Nuclear Weapons (Kaku no bokyaku no owari – Kakuheiki fukken no jidai), (in Japanese), Keiso Shobo, 2019, p. 244.

10 Brad Roberts, The Case for U.S. Nuclear Weapons in the 21st Century (Japanese translation by Masashi Murano) Keiso Shobo, 2022 (Original work published in 2015), p. 329.

11 The New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), which came into force in February 2011, was signed by the U.S. and Russia in April 2010 to replace the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I) after its expiration in December 2009. New START stipulates that the two countries reduce the number of deployed strategic nuclear warheads to below 1,550 and the number of missiles, bombers, and other delivery vehicles to below 800 (the number of actually deployed below 700) by 2018. This treaty expired in February 2021, but the two countries agreed to an extension of five years. See Disarmament Dictionary, etc.

12 Non-nuclear countries deploying and jointly operating nuclear weapons of nuclear powers on their territory. NATO members Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Turkey deploy U.S. nuclear arms under the nuclear sharing policy. See Disarmament Dictionary, etc.

13 Based on author’s interview with Iwamoto (Feb. 15, 2023).