Analysis of the implication of China's Economic Operation

China’s Investments in International Ports

under the Belt and Road Initiative

Yasuo Onishi

Introduction

The Belt and Road Initiative (hereinafter BRI) is the main pillar of the Xi Jinping regime’s policy and thinking in international affairs and its key economic doctrine. The BRI literally consists of one belt, the overland silk road, and one road, the maritime silk road. In line with the theme of the study group, this paper attempts to analyze the current state and issues of the maritime silk road, focusing on China’s investment activities in international ports.

Specifically, it will: first, present an overview of China’s investments in international ports and related ventures based on its strategic interests or policy intentions in the maritime silk road; second, examine the issues by looking at representative projects; and third, collect and organize data on China’s investment activities from the corporate side and examine issues reported and discussed in relation to the maritime silk road. Judging by the research interest of other study group members, the third aspect will be my unique contribution to this research project.

1. Strategic Goals of the Maritime Silk Road

In terms of the strategic goals of the maritime silk road, the first factor is economic security considerations. China relies heavily on fossil fuels for its energy needs. It imports oil and natural gas from overseas, mostly from the Middle Eastern countries. As a first step to diversify its import routes, China constructed an oil and natural gas terminal at the Kyaukpyu Port in Myanmar as part of its project to build a route connecting Myanmar to its domestic oil pipelines via Yunnan Province. It is also building the Gwadar Port in Pakistan. While the entire route has yet to function fully, an energy transport route eventually linking Gwadar in Pakistan to Tibet is being envisioned.

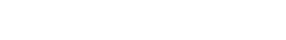

Second, China wants to promote the maritime industries and capture the markets for these industries. Under China’s key industrial policy, “Made in China 2025,” “marine engineering equipment and high-tech ships” comes fourth in the 10 strategic sectors, after (1) next-generation information technology; (2) automated machine tools and robotics; and (3) aeronautical and aerospace equipment. (Table 1)

Third, expand its influence in the shipping industry and maritime infrastructure. China is currently the leading maritime country in the world. Six of the top 10 container ports in the world are located on the Chinese mainland and Hong Kong, and China has continuously invested in ports along the shipping routes connecting these ports with Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. It is rather difficult to grasp the whole picture accurately, but a joint research by a British research institute and The Financial Times shows that since 2010, there were at least 40 port projects that Chinese and Hong Kong companies had undertaken or publicly known to be involved with, accounting for an overall investment of $45.6 billion. It is believed that 67% of container transport in the world pass through ports owned by China or ports in which it holds a stake[1].

Fourth, support for the overseas industrial parks that China has been building rapidly[2].Several Chinese government offices are involved with the construction of industrial parks overseas. The largest of these are the Overseas Trade and Economic Cooperation Zones initiated by the Ministry of Commerce, with 113 zones in 46 countries as of September 2018 that had received a total investment of $36.6 billion from Chinese companies. There are reports that among them, 82 industrial parks in 24 countries, accounting for $30.4 billion in investments (from 1,082 companies), were related to the BRI meaning they are located in countries along the silk road. Port investment serve to provide logistic support to the industrial parks. There are also many cases in which industrial parks were built close to ports.

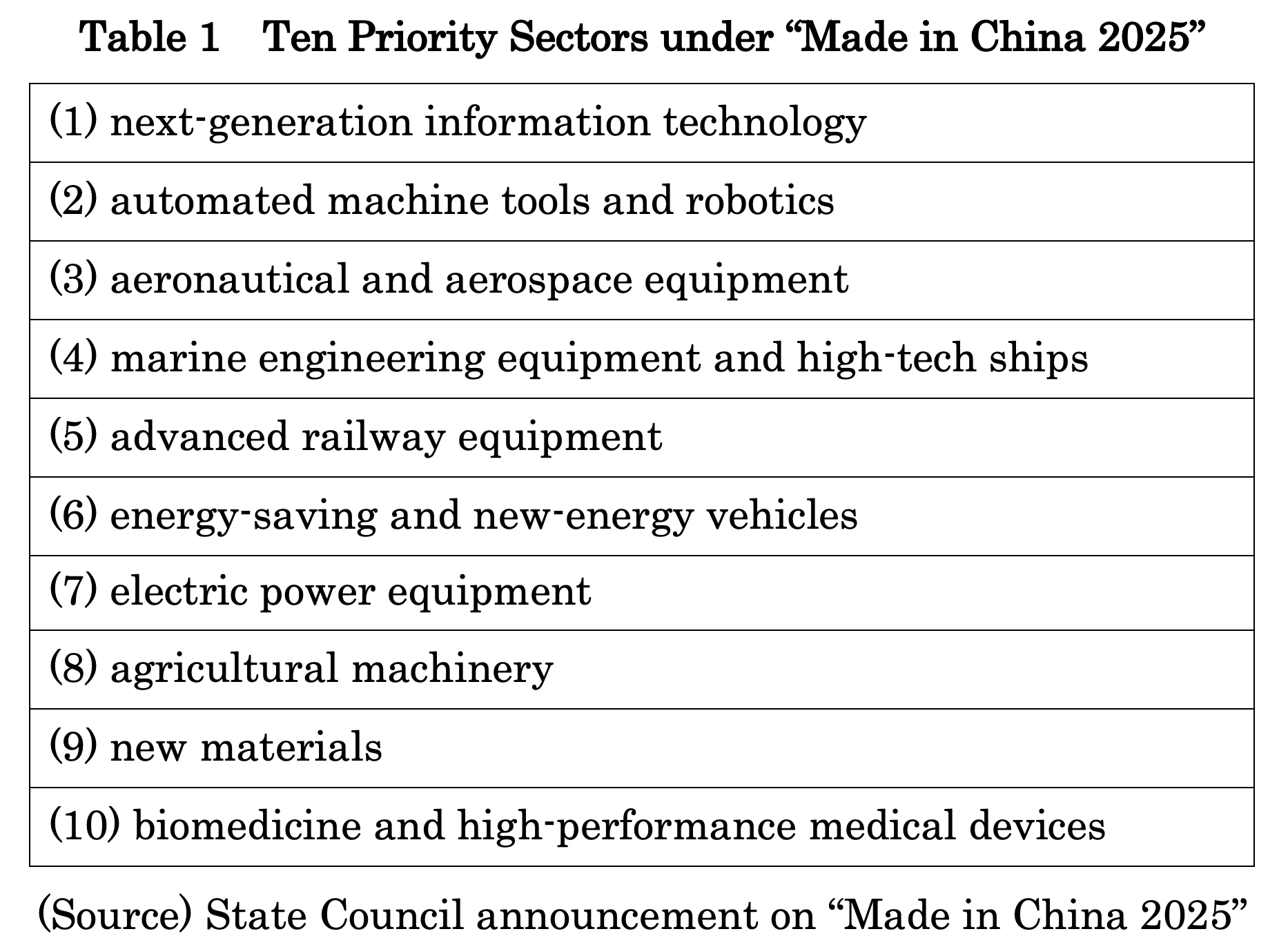

Fifth, a desire to expand the international presence of the Chinese navy can be cited as a major goal. However, a research report on this issue shows that there were only five ports where Chinese naval vessels had made port calls 10 or more times, even within the extended timeframe of 2003–2018. As shown in Table 2, most of them were in the Middle East[3].It is reckoned that the main reason behind the frequent port calls was the Chinese navy was participating in UN antipiracy operations. The Chinese navy has actually been most active in the South China Sea, but the military bases they had built on the islands in this sea area are not directly related to the BRI

2.The Maritime Silk Road’s Issues as Seen from Representative Projects

As stated in the previous section, China has engaged in large-scale investments in foreign ports for various reasons. It is not possible to evaluate them uniformly. The discussion here will focus on selected problems and issues concerning the overall BRI that are relevant to port investment.

(1) Diplomatic Frictions

The trickiest issue faced by the BRI is probably diplomatic frictions. Such frictions have emerged in bilateral relationships between China as the provider of funds and the recipient countries. First, it can be said that there are problems in the structuring process of investment projects. The dam project in Myanmar had been seen as problematic at the initial stage when the BRI was being publicized aggressively. This was because its feasibility study did not give consideration to the life of the local residents.

In the case of the Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka, a port investment project that has been reported on repeatedly, this had been planned as a project to invest in the political base of then President Mahinda Rajapaksa, who was in power when the project started. Estimates of its economic effects and prospects for the recovery of invested capital were way too optimistic. This author had an opportunity to visit the site in September 2017. It was evident that there were no industries in the port’s hinterland, and it was also unlikely that there would be any transportation needs. At that time, the gantry cranes at the port were not in operation, and the port was merely being used as a transit point for used cars.

(2) Insolvency and the Debt Trap

Several countries came to accumulate unrepayable debts with China and fall into insolvency as a result of such sloppy estimates. In a report in 2018, the U.S. think tank Center for Global Development published a controversial debt crisis map classifying countries of the world into three groups according to the level of their debt to China: “high,” “significant,” and “low.”

What complicated the problem is that when resolving insolvency, conditions that compromise the sovereignty of the debtor country have been set as security for its debt. In the case of Sri Lanka, debts incurred by the Hambantota project was resolved by leasing the port to a Sri Lanka-China joint venture (70% Chinese capital, 30% Sri Lankan capital) for 99 years. The terms “99 years” and “lease” have an offensive ring to them, and this arrangement became controversial internationally. Similar cases have also occurred in other countries that the term “debt trap” dominated news headlines not so long ago. However, Hambantota is a commercial project (the contractor being China Harbour Engineering Company), and upon a closer look at this case, it has to be noted that no other assets were available as security and Sri Lanka, in fact, also opted for this solution.

Furthermore, the problem of excessive debts did not happen only after the BRI started. It has mostly been the consequence of China’s approach to foreign aid. Only a small portion of China’s aid conforms with OECD standards, and most of this is provided under its so-called “foreign economic cooperation” scheme. Under this scheme, China tends to take the lead in the structuring process of aid projects. While its interest rates and repayment terms are more favorable than commercial loans, they are significantly more stringent than ODA, which eventually become a strain on the finances of the recipient countries. Even Pakistan, which China regards to be its ally, is plagued by excessive debts. This country is reported to have sought aid from IMF.

(3) China’s Response

China has, by no means, neglected the above diplomatic frictions and debt issues. It has to be noted that China had begun to adjust its policies at an early stage.

In a speech in August 2018 at a symposium on the mission of the BRI to mark its fifth anniversary, Xi Jinping stressed, among other things, that: (1) the BRI is not a “China Club”; it is an open platform; (2) projects need to benefit the livelihood of the people of the recipient countries; (3) Chinese companies must abide by local laws in their investments and operations; and (4) environmental conservation and social responsibility are important.

Later, at the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in September, Xi outlined the “eight major initiatives” ((1) industrial promotion, (2) infrastructure connectivity, (3) trade facilitation, (4) green development, (5) capacity building, (6) health care, (7) people-to-people cultural exchange, and (8) peace and security) as China’s basic policy on cooperation with Africa. The Forum on China-Africa Cooperation Beijing Action Plan was adopted at this conference to implement these initiatives. It was also announced that a total of $60 billion in financial aid to be provided by China over three years from 2019 to 2021 would consist of: (1) $15 billion in grants, interest-free loans, and concessional loans; (2) $20 billion of credit lines, (3) $10 billion in special China-Africa fund for development financing, (4) $5 billion special fund for financing imports from Africa, and (5) $10 billion of direct investment by Chinese companies. It can be said that this was China’s answer to the international community’s criticisms of lack of transparency of its aid.

Subsequently, at the Second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation held (in April 2019) to determine the direction of the BRI in the next five years, Xi delivered a speech that summarized the above points.

3.Chinese Companies’ Investment Activities

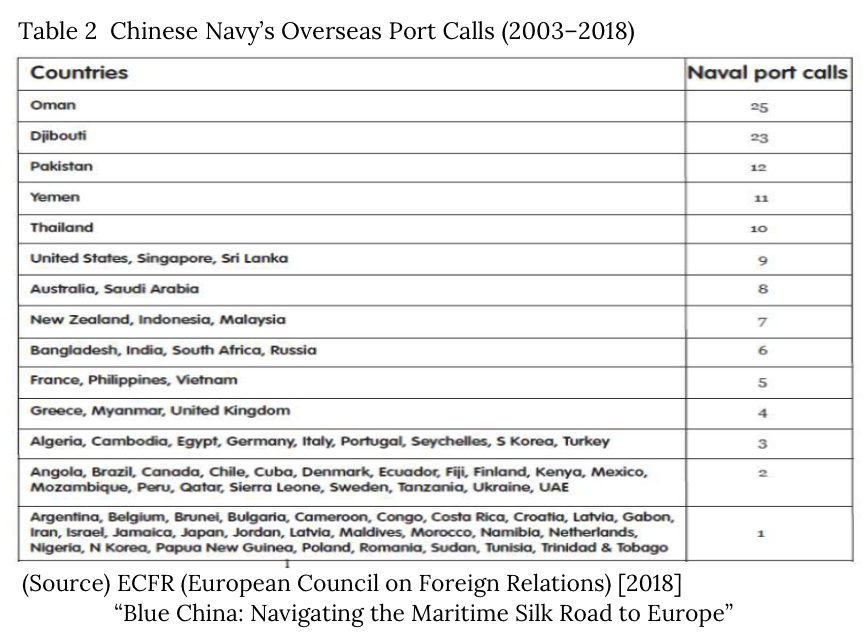

Turning to Chinese companies’ investment activities from the corporate perspective, Diagram 1 shows the ratio of overseas investments by state-owned and non-state-owned enterprises from 2006–2017. While state-owned enterprises accounted for 80% in the beginning and their share was reduced gradually as the ratio of non-state-owned companies increased, they still made up 49.1% of overseas investments in 2017. State-owned entities still have a strong presence in overall overseas investments.

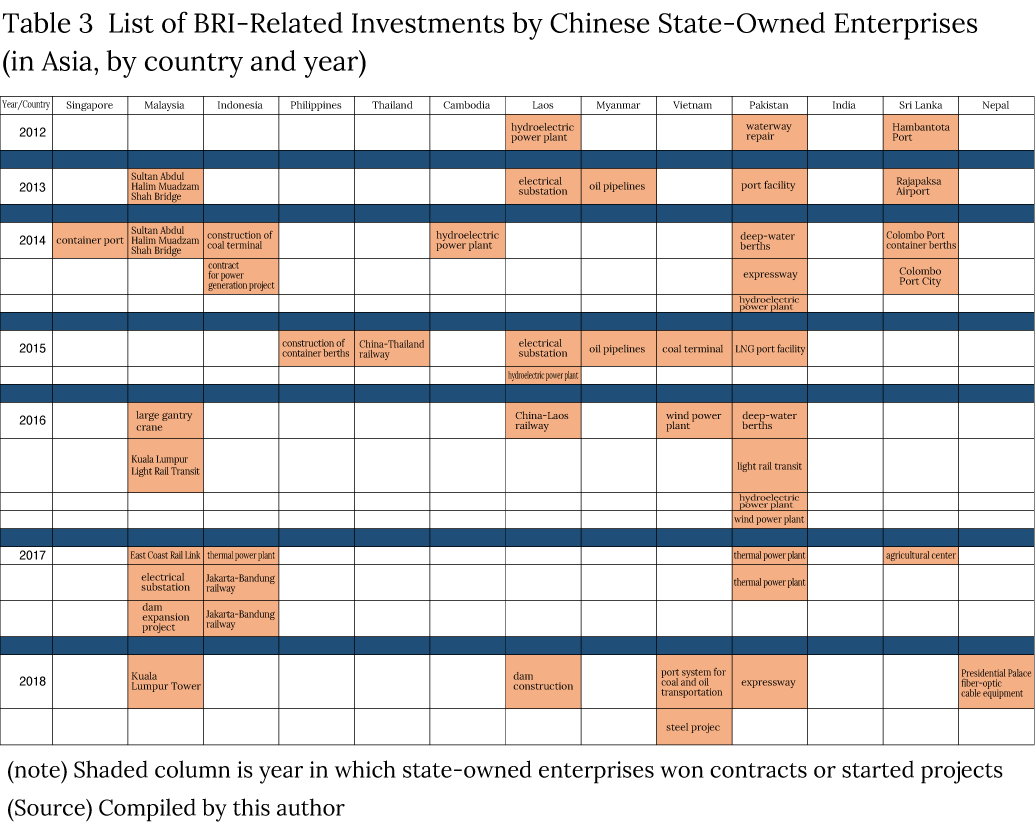

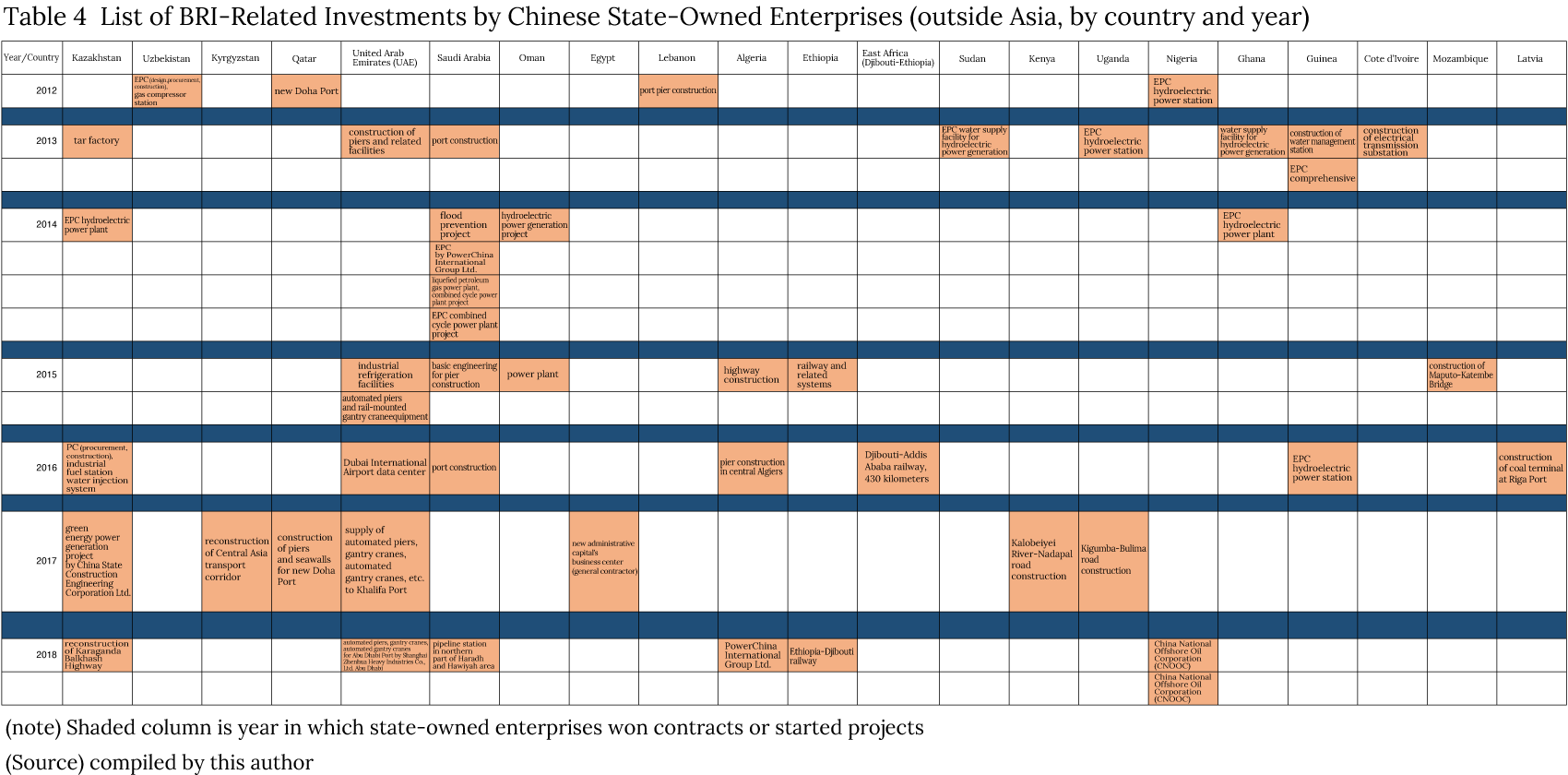

This author further chose some 20 companies that have been most active in overseas investments in recent years, collected data from their websites and media reports, and used such data to create a matrix of countries in which they invested and the year in which the investment projects started (including year contract was won). The data in this matrix includes not only port projects, but all projects these companies were involved with. Projects were then divided into those undertaken in Asian and non-Asian countries, and the representative projects are listed in the columns in Tables 3 and 4.

These two tables demonstrate that many of China’s state policy projects are undertaken by leading state-owned enterprises as has often been reported in the media. However, as stated earlier, this system made it difficult for the wishes of the recipient countries to be reflected in the decision-making process of investment projects. It must be emphasized again that this is not only a source of resentment on the part of the recipient countries but also one of the causes of insolvency.

Conclusion

As stated earlier, China’s investment in overseas ports had been in full swing even before the BRI started. China is a maritime power that relies heavily on foreign trade, so securing access to ports overseas is of critical importance. Therefore, its investment activities are understandable. However, it is also a fact that with the introduction of the BRI port investments were reviewed and restructured in relation to other infrastructure investments.

In Pakistan, a key target of the BRI in addition to the Gwadar Port, several power plant, expressway, and railway projects are being implemented simultaneously as part of the masterplan called CPEC (China-Pakistan Economic Corridor), which is one of the six economic corridors under the BRI China is also consciously linking overland infrastructure to port infrastructure in the other economic corridors, which reflects its expectations for the BRI.

In other words, China’s goal is to form an economic sphere by expanding its economic influence with the economic corridors at the core. For sure, such an economic sphere does not exist yet, but China’s goals for the future certainly need to be taken into consideration. In that sense, it is necessary to continue to closely watch the maritime silk road and the BRI.

(Submitted on Feb. 3, 2020)

1 “How China rules the waves”, Financial Times 2017年1月25日付け報道

2 工業団地に限定されず、農業団地や商業・貿易団地、研究開発団地がある。

3 European Council on Foreign Relations, 2018 “Blue China: Navigating the Maritime Silk Road to Europe”

4 Hurley.J.et.al (2018) Will China’s Belt and Road Initiative Push Vulnerable Countries into Debt Crisis?

参考文献

(英語文献)

European Council on Foreign Relations, 2018 “Blue China: Navigating the Maritime Silk Road to Europe”

(中国語文献)

中華人民共和国商務部・国家統計局・国家外匯管理局2018『2017年度中国対外直接投資統計公報』(中国商務部HP)