Analysis of the implication of China's Economic Operation

“Chinese Foreign Aid Data Analysis” Project

The Background to China’s Overseas Port Investments

Bonji Ohara

Senior Fellow

Sasakawa Peace Foundation

Introduction

This project aims at collecting and analyzing data on China’s investments in overseas ports to confirm the hypothesis that “this is being conducted as part of its diplomatic strategy.” However, it is impossible to analyze all of China’s overseas port investments or to collect data reflecting China’s diplomatic strategy in this paper. Therefore, it is difficult to confirm the hypothesis itself. What can possibly be achieved here is to deduce if China had any non-commercial motives in specific port construction investment projects. This paper looks at the Gwadar Port in Pakistan as an example to examine if China had non-commercial motives in its investment.

China’s external loans and overseas investments often have the image of a “debt trap” in which loans exceeding the repayment capability of the recipient country are provided, thus resulting in default. This in turn enables China to acquire management and other rights for the infrastructure, and such is actually its real purpose in these projects. Furthermore, not all of the ports China invested in become commercially viable after completion. For example, regular monitoring of shipping operations at the Gwadar Port in Pakistan, the Kyaukpyu Port in Myanmar, and other facilities shows that ships rarely use these ports. It is said that China had planned the ports for military purposes and not for commercial use in the first place.

On the other hand, many projects related to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) are not necessarily being undertaken based on the intent of President Xi Jinping or the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee. It is reckoned that they are executed by the companies involved, which use available loans to pursue short-term profit. Since these investments are made even with uncertain prospects for commercial success or the banks providing capital failing to conduct thorough feasibility studies, it is said that when the recovery of investment becomes doubtful, the corporate investors scramble to at least acquire management rights, for fear of criticism from the CPC leadership.

While it is difficult to discern the motives of Chinese companies involved with overseas investments, this paper studies the case of Gwadar Port – which can hardly be called a commercial success – as an example by focusing on its relation with the activities of the Chinese navy as a tool for implementing China’s diplomatic strategy.

Gwadar Port’s Commercial Value

Phase One of the construction work for the Gwadar Port (2002–2006) was undertaken with joint funding from the Chinese and Pakistani governments. This phase of the project cost a total of $248 million, with China providing $198 million in subsidies, interest-free loans, concessional loans, buyer’s credit, and other forms of financing[1].

However, Gwadar Port can hardly claim to be a successful commercial venture. Cargo handling has been below capacity and the port has been underused. In summer 2019, COSCO Shipping Lines, a subsidiary of China COSCO Shipping Corporation Limited, terminated its container services[2].While total investment in Phase Two of the project, initiated in 2015, is said to be $1.02 billion[3], only 60% of the port’s free trade zone has been completed[4].

In reality, very few ships ever use the Gwadar Port. It is obvious from the number of ships calling at the port (Table 1) that Gwadar is not a profitable commercial port. Furthermore, although infrastructure at the port had basically been completed in 2015[5], the number of ships has not increased, but has rather been diminishing.

Furthermore, although Gwadar Port has a large container loading area measuring 48,278 square meters and 6,875 square meters of container stacking area for storing empty containers[6], most of the ships entering this port are bulk ships and almost none are container ships. This means that the rather impressive facility is underused, which points to problems in the Gwadar Port’s handling of containers. The port actually has 200-meter berths that can handle cargo ships up to 50,000 tons with 12.5-meter draft [7].

If China indeed intends to use Gwadar for non-commercial purposes, logistical supply for naval vessels is conceivable. It is not hard to imagine that the Chinese navy would want to use this port that is strategically located at the mouth of the Strait of Hormuz. In a paper in May 2018 that predicted the expansion of the activities of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy, the U.S. think tank Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) wrote: “The prospect of the PLA Navy in Gwadar poses greater security questions, as it forms another link in China’s efforts to expand its maritime presence in the Indo-Pacific region [8].

However, there is no evidence that China had built the Gwadar Port with a military agenda in mind in the first place. In relation to this point, it is also necessary to analyze the level of the PLA’s use of Gwadar.

PLA Navy’s Activities in Pakistan

On May 23, 2010, Chinese Minister of National Defense Liang Guanglie visited Pakistan. His Pakistani counterpart stated on this occasion that “the Chinese military delegation’s visit to Pakistan helps strengthen the bilateral relationship between the two neighboring countries[9].”

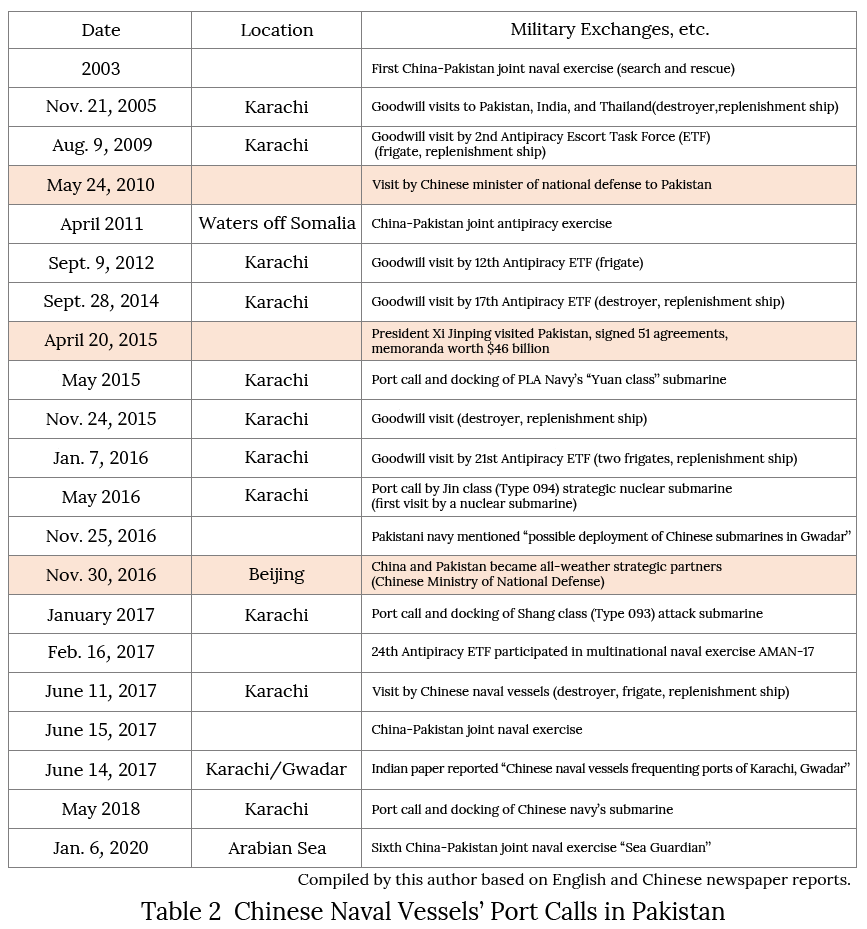

Since this visit, there has indeed been an increase in port calls by Chinese naval vessels to Pakistan, but they were mere goodwill visits by the antipiracy units, which China calls “escort task forces,” on their way to or returning from their mission in the Gulf of Aden.

Chinese naval vessels began visiting Pakistan regularly every year from 2015. This was a year in which China touted the strengthening of cooperation with Pakistan. Xi made a two-day visit to Pakistan from April 20 and signed 51 agreements and memoranda worth $46 billion[10].Among them, funding was provided for multiple cooperation projects on power generation, which was the main interest of the Pakistani government. China also provided loans for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which involved the construction of highways, railways, airports, and pipelines connecting western China to Gwadar Port via northern Pakistan, to secure access to the Arabian Sea[11].

However, as can be seen from Table 2, most Chinese naval vessels and submarines called on the port of Karachi and not Gwadar. The Chinese navy’s submarines also docked in Karachi for maintenance. On the other hand, a plan to build an artificial island in Gwadar Dockyard has been scrapped from the masterplan. It is possible that this port will not be able to achieve the originally envisioned level of naval vessel maintenance and supply capability, including repair capability[12].

Another possibility is that Chinese naval vessels’ port calls in Gwadar have not been reported by the media. This is evidenced by a report in the Indian media on June 14, 2017, citing an intelligence agency, that the Chinese navy’s surface vessels and submarines were frequenting the ports of Karachi and Gwadar[13]. It is possible that the imposition of press censorship has prevented media reporting on port calls in Pakistan from 2018 onward.

Nevertheless, there is no doubt that the Chinese navy, particularly its submarines, is becoming increasingly active in the Indian Ocean. Furthermore, China does not only send its submarines to visit; it is reckoned that it is also obtaining hydrographic and other data in the Indian Ocean by exporting submarines to the Southeast Asian and South Asian states. Bangladesh decided in 2013 to purchase two second-hand “Ming class” diesel-electric submarines from China, and these submarines entered service in March 2014. Thailand also decided in April 2014 to buy one new “Yuan class” submarine. The “Yuan class” is two generations newer than the “Ming class,” and this country is contemplating purchasing two more. Pakistan discussed the procurement of eight Chinese submarines when Xi visited in 2015, and this was officially confirmed by China in the following year. These eight submarines were “Yuan class” diesel-electric submarines, four of which would be built in Pakistan[14].

Conclusion

It is a fact that China has actively invested in the construction of the Gwadar Port, but this port has yet to become commercially viable. On the other hand, the media have not reported any visits by Chinese naval vessels, particularly submarines, to Gwadar. However, according to an Indian intelligence agency, the Chinese navy’s surface vessels and submarines had been frequenting the ports of Karachi and Gwadar. Furthermore, the Pakistani navy mentioned the possibility of deploying Chinese naval vessels in Gwadar Port in November 2016[15].

While this situation does not rule out the possibility that China’s investment in the Gwadar Port was aimed at using it as an operational base to expand its naval activities, there is also no conclusive proof of this or any connection at all between Gwadar and the Chinese navy.

It is always difficult to determine the motives of any country. More so in the case of China because information disclosure is controlled by the CPC. What can be said in this paper is that it is important to gather data to serve as objective evidence and that tremendous efforts will be required to analyze such data. Persistent efforts need to be made to collect data, create databases, and improve the visibility of such data, in order to enhance transparency to facilitate multifaceted analysis.

(Submitted on March 3, 2020)

1 ‟瓜达尔港“一波三折”建设路”≪人民网≫2015年4月20日。

http://paper.people.com.cn/gjjrb/html/2015-04/20/content_1555581.htm

2 ‟China-Pakistan Gwadar Port runs into rough weather”, The Economic Times, Sep 10, 2019.

https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/world-news/pakistan-china-gwadar-port-runs-into-rough-weather/articleshow/71041565.cms

3 ‟Zhuhai Port scores big with deal in Pakistan”, China Daily USA, October 30, 2015.

http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/epaper/2015-10/30/content_22326165.htm

4 ‟Gwadar Port City”, CPEC China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.

http://cpecinfo.com/gwadar-port-city-1/

5 ‟瓜达尔港“一波三折”建设路”≪人民网≫2011年04月20日。

http://paper.people.com.cn/gjjrb/html/2015-04/20/content_1555581.htm

6 ‟PORT PROFILE”, Gwadar Port Authority

http://www.gwadarport.gov.pk/portprofile.aspx

7 前出‟PORT PROFILE”.

8 ‟Pakistan’s Gwadar Port - A New Naval Base in China’s String of Pearls in the Indo-Pacific”, CSIS, March 2018.

https://www.csis.org/analysis/pakistans-gwadar-port-new-naval-base-chinas-string-pearls-indo-pacific

9 ‟中国国防部长出访巴基斯坦引印度关注”, RFI, 2010年5月24日。

http://www.rfi.fr/cn/%E4%B8%AD%E5%9B%BD/20100524-%E4%B8%AD%E5%9B%BD%E5%9B%BD%E9%98%B2%E9%83%A8%E9%95%BF%E5%87%BA%E8%AE%BF%E5%B7%B4%E5%9F%BA%E6%96%AF%E5%9D%A6%E5%BC%95%E5%8D%B0%E5%BA%A6%E5%85%B3%E6%B3%A8

10 ‟CPEC Long Term Plan”.

https://www.pc.gov.pk/uploads/cpec/LTP.pdf

11 「発電所や高速道路事業に中国が大規模融資-習国家主席のパキスタン訪問-」『JETRO』20115年05月22日。

https://www.jetro.go.jp/biznews/2015/05/b6eb649388b361a0.html

12 ‟Gwadar News: Artificial Island Built in Gwadar Dockyard is Dropped”, Gwadar Dock, March 1, 2020.

http://gwadardock.com/index.php/2020/03/01/gwadar-news-artificial-island-built-in-gwadar-dockyard-is-dropped/

13 ‟Chinese warships frequently visit Karachi, Gwadar in bid to expand presence in Indian Ocean”, India Today, June 14, 2017.

https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/indian-ocean-china-warships-submarines-navy-presence-goodwill-visit-peoples-liberation-army-982649-2017-06-14

14 「中国、インド洋沿岸国に潜水艦輸出 データ収集狙いか」『朝日新聞DIGITAL』2018年1月14日。

https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASL1D4FXVL1DUHBI00X.html

15 ‟巴基斯坦:中国海军或在瓜达尔港部署舰艇”≪日本经济新闻≫2016年11月26日。

https://cn.nikkei.com/politicsaeconomy/politicsasociety/22547-2016-11-28-08-51-03.html