- Top

- Publications

- Ocean Newsletter

- Wavering Unity in the Pacific Islands Region

Ocean Newsletter

No.510 November 5, 2021

-

Wavering Unity in the Pacific Islands Region

KOBAYASHI Izumi

Professor, Osaka Gakuin University / President, Japan Society for Pacific Island StudiesThe Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) has contributed greatly towards increasing the level of international recognition that Pacific Island States enjoy today. However, the region’s sense of unity is weakening as some countries begin to declare their withdrawal from the PIF and conflicts of interest appear not only between island States, but also within domestic politics. This may very well have a substantial impact on Japan’s diplomacy towards the island States. -

The Role of Finance towards Large-scale Adoption of Offshore Wind Power: Publishing a Finance Guidebook

ADACHI Shinichi

General Manager, Japan Wind Power AssociationJapan has seen rapid progress in the development of offshore wind power in recent years. Japan Wind Power Association members began a task force, which, through cooperation from both the public and private sectors, created the country’s first guidebook on practices concerning financial aspects of supporting large-scale offshore wind power generation projects. -

The Little Giants of the Sea: Copepods

UEDA Hiroshi

Professor Emeritus, Kochi UniversityCopepods are zooplankton found throughout the world’s oceans and said to be the animal forming the largest biomass on earth. They sustain mankind as the most important food source for larvae of many fish species. Copepods also play an important role in transporting to the deep sea the large amount of carbon that is fixed on the ocean surface by phytoplankton. Though they don’t stand out, these “little giants of the sea” are extremely valuable to mankind.

Wavering Unity in the Pacific Islands Region

[KEYWORDS] Pacific Island States / regional solidarity / island nations diplomacyKOBAYASHI Izumi

Professor, Osaka Gakuin University / President, Japan Society for Pacific Island Studies

The Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) has contributed greatly towards increasing the level of international recognition that Pacific Island States enjoy today. However, the region’s sense of unity is weakening as some countries begin to declare their withdrawal from the PIF and conflicts of interest appear not only between island States, but also within domestic politics. This may very well have a substantial impact on Japan’s diplomacy towards the island States.

A Vast Ocean, A Peaceful Ocean

What is the difference between the Atlantic and the Pacific? Put simply, the Atlantic Ocean is almost empty, while the Pacific Ocean is scattered with adjacent seas and islands. With this in mind, I once explained to someone, “In Japanese, we add a dot to the character for big “大” to represent an island, making it into “太”, and use it in the Japanese word for the Pacific (太平洋).” In response, the person asked a pointed question: “Then, why does the Japanese word for Oceania (大洋州) not include the dot?” As he pointed out, in actuality, the dot in the character “太” does not represent islands. The correct explanation is that the name derives from the English “Pacific Ocean” (originally a Latin term), meaning “peaceful sea” as named by Ferdinand Magellan, an adventurous voyager during the Age of Exploration.

However, since the 16th century, when Magellan first named the sea, it has been anything but peaceful. Instead, it has been a stage for action in the struggle for supremacy, with great powers coming and receding. Eventually, the islands became colonies of the major powers, then battlefields, and finally, even test sites for nuclear weapons. It is an entirely different region from the Atlantic, which is primarily ocean. Its history was influenced by its topographical and geographical factors, which are formed from its adjacent oceans and islands. The islands’ inhabitants have continued to be at the mercy of the intentions and actions of the major powers. It is, therefore, ironic that many in the outside world still think of the South Pacific as a paradise.

The international environment surrounding these islands has changed drastically since the beginning of the 21st century. There have been dramatic developments in means of communication and transmission, global warming and climate change, and a growing awareness that marine resources are the common property of humanity. This shift means we can no longer ignore the big voices of small political actors who are asserting themselves against the backdrop of this vast ocean.

The Emergence of Island States and Regional Unity

The South Pacific Forum (SPF), established in 1971, has been the voice of these small island nations in the international community. The first state to emerge in the region was Western Samoa (now the Independent State of Samoa) in 1962. The Commonwealth colonies then gained independence one by one. Finally, in the 1980s, two independent states emerged from the U.S. Trust Territory of Micronesia, and in 1995 a third, Palau, was added, bringing the total to the current 14 island nations (including the Cook Islands and Niue).

However, political independence does not mean that a nation has immediately become self-reliant. Therefore, these small States needed to join together in solidarity, presenting themselves in unity to the international community. The SPF is a testament to that unity, and steadily developed to provide regional solidarity. In the year 2000, after the three Micronesian nations in the Northern Hemisphere became members, it dropped the South from its name to become the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF). The PIF has made an extraordinary contribution to the international recognition of the Pacific Island States as we know them today.

However, in February 2021, a situation occurred that shook its unity. The five Micronesian nations objected to the appointment of the Secretary-General and declared their withdrawal from the PIF. Traditionally, personnel matters were determined through discussions. It was Micronesia’s turn to have an individual appointed to the role, but discussions were inconclusive, leading to a vote on the matter. As a result, a Polynesian individual was elected by a vote of 9 to 8. In the 50-year history of the PIF, a director-general had been elected by vote only once before. Hence, this was an unusual conclusion to the situation.

With just four months before the official withdrawal procedures are complete, the island states are not evenly divided in their opinions. Some, such as Fiji and Papua New Guinea, are trying to discourage withdrawal, while others are saying, “If they want to leave, they can go ahead.” When the PIF held a remote summit meeting this past August to commemorate its 50th anniversary, inviting U.S. President Biden, one country, Nauru, was sent to attend the meeting to see the proceedings, but four other Micronesian countries were absent. The possibility that Micronesia may completely withdraw from the PIF cannot be ruled out. If this happens, it will have a significant impact on the Pacific Alliance Leaders Meeting (PALM), which Japan has hosted for a quarter of a century for the leaders of PIF member countries. Conventional diplomacy with the island nations themselves may also need to be reviewed.

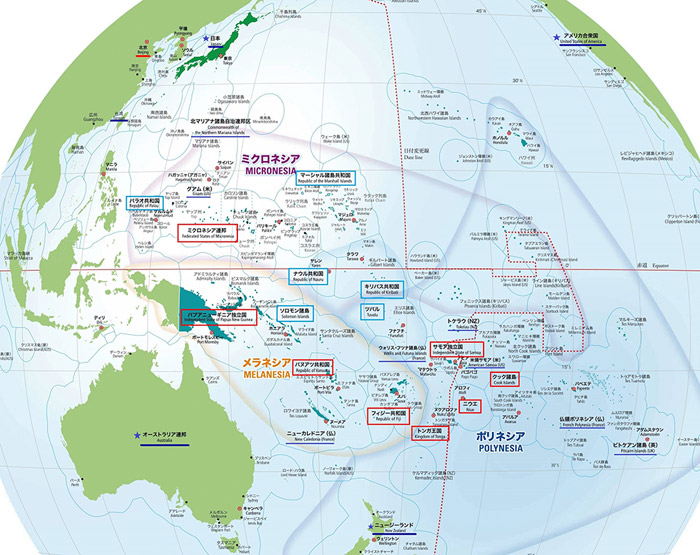

Pacific Ocean Map Created by the Sasakawa Peace Foundation’s Pacific Island Nations Program

Pacific Ocean Map Created by the Sasakawa Peace Foundation’s Pacific Island Nations Program

Changes to Surrounding Environments and Domestic Politics

Nevertheless, this discord among PIF member countries did not arise out of nowhere. Growing international interests have led to a reduced sense of regional unity. Specifically, unprecedented conflicts of interest and political issues have emerged among the island countries and in domestic politics over the relationship with new donor countries (supporting countries). This conflict has increased emphasis on geographic proximity and joint actions by nations of similar economic size. It is also why unconventional forms of subregional solidarity have begun to emerge, such as the Melanesian Spearhead Group* and the Parties to The Nauru Agreement (PNA), which consist of countries rich in fishery resources, and even the Micronesian Presidents’ Council. Except for areas of commonality such as having the history of being under the same suzerain power and a similar background of independence, the islands have different languages and cultures and are separated by large distances, so they do not need to unite. Sub-regionalization would therefore be one reasonable direction.

A significant factor leading to this situation has been China, which has strengthened its expansion into the Pacific since 2000. China began providing aid to the islands assertively, attempting to exclude Taiwan from the region. These actions had a significant impact on Taiwan and existing donor countries like Australia, New Zealand, the United States, and Japan. For example, Japan’s ODA to the region had been around 10 billion yen per year, but at the 4th PALM in 2006, Japan pledged 45 billion yen over three years, or a 50% increase. This change was in response to China’s immediate previous announcement of 40-billion-yen worth of aid over three years. After that, the ODA continued to increase by 50 billion yen, 500 million dollars, and 55 billion yen per PALM. Although the Japanese government says it “does not attempt to compete with other countries when determining aid amounts,” there is a clear awareness of China in its decision. Other donor countries are similarly increasing their involvement in the islands in response to China.

The island countries are sensitive to these changes in their neighbors, resulting in a structure of conflicting interests, not only in inter-island relations but also in domestic politics.

When this happens, the simple unity provided by the PIF, which was once required for international appeal, no longer makes sense. For that reason, Japan must now try to understand the diverse individual wills of these countries rather than the will of the Pacific island group as a whole, whether in diplomacy or private-sector exchanges. (End)

- Note:The Melanesian Spearhead Group is a political group organized by Melanesian ethnic nations and regions such as Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Fiji, and New Caledonia for the purpose of independence and solidarity of Melanesian ethnic groups.